How to Be Strategic with Scaffolding Strategies

By Karin Hess

When you choose a scaffolding strategy, do you first consider the intended learning targets for the lesson and the reasons why particular students might be struggling to achieve them?

When you choose a scaffolding strategy, do you first consider the intended learning targets for the lesson and the reasons why particular students might be struggling to achieve them?

Or do you think about how to use scaffolding to move even the highest performing students forward? Being strategic about scaffolding can advance learning and deepen the engagement of every student.

Scaffolding strategies need to be used strategically. For example, a strategy intended to support executive functioning or language development may not be effective for deepening content knowledge and thinking.

Educators should begin by asking themselves: Why did I choose this strategy? Does it match my learning target and how will it optimize learning for some or all of my students?

Dispelling Some Common Myths

I’ll share some ideas about making good choices below. First, let’s clear up three common myths about scaffolding.

Myth #1: Scaffolding is the same as differentiation.

Many educators – and even educational materials – confuse scaffolding with differentiation. They are actually quite different. An easy way to remember the difference is that scaffolding provides steps to support completing a task, while differentiation gives students different choices as to which tasks they will complete.

When instruction is differentiated, students choose and work on different – and often comparable – assignments. I first used differentiation with intent when I was teaching middle school. I created assignment menus that differentiated the content (different texts, materials, situations, or topics), the processes used (depth of engagement with the content/DOK, working alone or with someone, etc.), or the products students developed as evidence of their learning. Choice boards, menus, and stations are often used during a unit of study to offer optional activities to students.

In contrast, scaffolding strategies are ways to enable each student to successfully access or exceed grade-level content, complete a basic to advanced assignment, and grow in confidence and independence as a learner.

Myth #2: Scaffolding is always temporary.

Actually, many of the same scaffolding strategies (e.g., breaking down a task into smaller parts, co-creating an anchor chart to build conceptual understanding) can be used independently later on with increasingly more complex tasks.

Scaffolds are not only for struggling students; high-performing adults break down complex tasks into smaller chunks and use models and peer feedback to improve their understanding of new information. Think of it this way – a painter always uses some type of scaffolding to paint a ceiling.

Myth #3: Scaffolding is used to change the overall intended rigor.

A scaffolding strategy can reduce the cognitive demand on a learner’s working memory during learning, but it does not change the rigor of the learning activity.

While decoding skills are important, decoding words is not the primary focus in this learning activity. Likewise, when a student uses a calculator to compute operations with large numbers or decimals so they can check their estimations, working memory is freed up from time it would take to hand calculate the same problems.

Knowing what the learning targets are helps teachers determine which scaffolds are most appropriate for that lesson and for particular students – in other words, the scaffolding activity is in their Zone of Proximal Development/ZPD. Scaffolding is used to ensure that even though a student may struggle, the struggle will be productive.

Think of scaffolding as a bridge that can either (a) make content more accessible (“chunking” texts, focused discussions, building background knowledge) or (b) make multi-step tasks more manageable (group data collection, breaking tasks into smaller parts with checkpoints).

Deciding When to Use Scaffolding

Three common areas of support can be useful for educators to consider when helping students develop the skills needed for accomplishing more challenging tasks or understanding complex information.

- deepening content knowledge,

- facilitating executive function, and

- supporting language and vocabulary development

Strategic scaffolding at one Depth of Knowledge (DOK) level will usually support students in advancing to the next DOK level. Below, I describe a few strategies at each DOK Level for each different instructional purpose. (For a complete set of strategies, download Karin’s PDF.)

Scaffolding Purpose 1: Deepening Content Knowledge and Connecting to “Big Ideas”

Many strategies used to deepen learning can naturally flow out of activities designed to build language skills or support executive function. For example, developing an anchor chart with students on the steps used to solve a nonroutine mathematics task supports executive functioning and leads to later use of the chart, triggering reminders of each step while solving new problems.

Scaffolding Strategies that

Deepen Knowledge

at Different DOK Levels

DOK 1 – The “DAILY 10” Playlist

The impact of background knowledge on reading comprehension and schema building cannot be overstated. To use this strategy, a playlist of at least six short print and nonprint resources on a topic (e.g., photos, political cartoons, articles, websites related to social studies or science unit) is created for students at the beginning of the week.

For no more than ten minutes a day, individuals or groups of students choose one resource to read/listen to and take a few notes. Notes are not graded. Class discussions and journal writing can be used to connect the growing background knowledge to the ongoing unit of study.

DOK 3 – Carousel Feedback

This strategy is a variation on carousel brainstorming where small groups move from one station to the next, generating ideas on different subtopics, writing them on large charts for the next group to read and add to.

The teacher prepares 4 or 5 large charts with a different question prompt or problem-solving task on each one. Students are heterogeneously grouped, with each group using a different colored marker for their responses. Each group reads the problem at their table and begins to solve it on the chart paper.

Time is called again, and groups rotate to a third problem, using the same checking and justifying process as before. In the last round of rotations, groups develop a justification supporting the solution based on calculations and notes of the other teams. Carousel strategies promote deeper discussions and how to collaboratively develop reasoning with supporting evidence.

Scaffolding Purpose 2: Facilitating Executive Function and Application of Skills and Processes

Students with poor executive function struggle to sustain focus and engagement with lengthy texts and multi-step tasks. Executive function also affects the ability to set and monitor goals and maintain a positive self-image as a learner. Executive functions are a diverse, but related, set of skills that help learners to initiate, monitor, and complete longer and more complex multi-step tasks. Scaffolding strategies can support:

- Initiation – The ability to begin a task or activity and generate ideas, responses, or problem-solving strategies (e.g., group brainstorming or problem solving).

- Working Memory – The capacity to hold information in mind for the purpose of sustaining engagement with a longer text (e.g., chunking texts).

- Planning and Organization – The ability to manage current and future-oriented task demands (e.g., learning logs).

- Self-Monitoring – The ability to monitor one’s own performance and to measure it against some standard of what is needed or expected (e.g., conferencing).

Scaffolding Strategies that Support

Executive Function

at Different DOK Levels

DOK 2: A Card Pyramid Helps Summarize Information

The card pyramid strategy can be used with numbered sticky notes or index cards to break down information in a text. Ideally, partners work together to build the pyramid and then take turns orally summarizing information before completing a written summary.

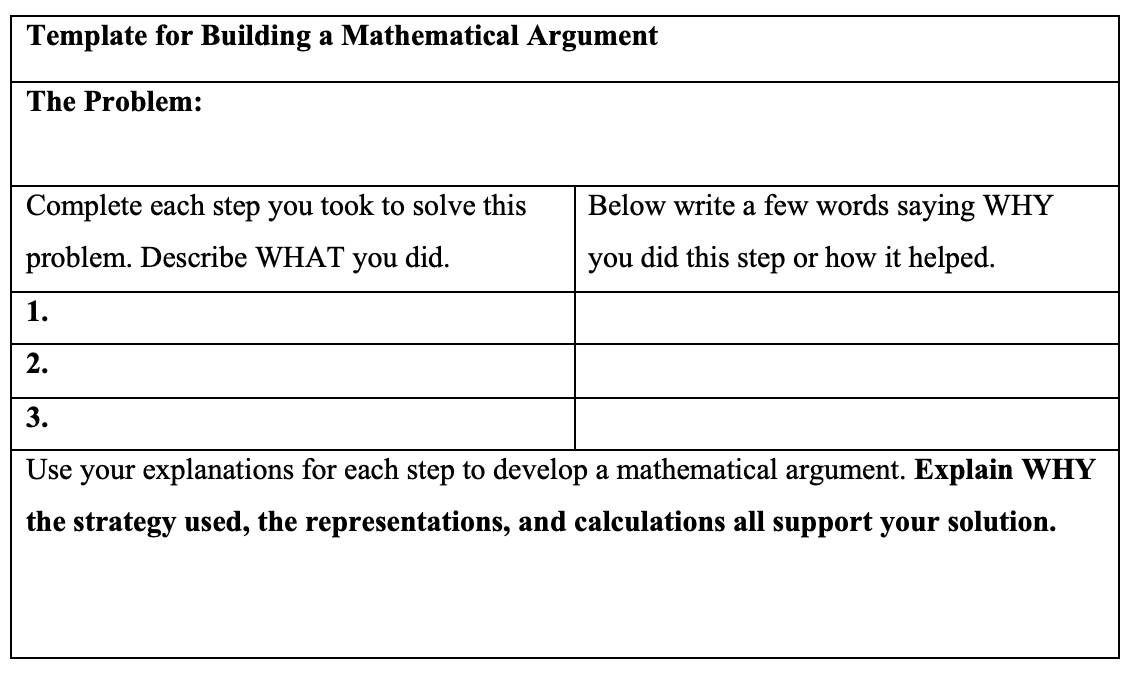

DOK 3 – Building a Mathematical Argument

Building a mathematical argument is as hard to teach as it is to learn. In this strategy, partners divide their paper in half lengthwise. On the left, the students work through each step to solve the problem. On the right, they explain why they did each step or how that step helped (e.g., my diagram shows how the candy bar was divided; I labeled each fractional part to show…). This scaffolding strategy is effective because it breaks down HOW we got to the solution and slows down thinking so we can explain WHY we did each step.

Scaffolding Purpose 3: Supporting Language and Vocabulary Development

Building vocabulary and using language are foundational to learning in all content areas. One method for building vocabulary is to prioritize and reinforce the essential language needed for learning in any content area. Informal ways for teachers to strategically support language development include using visuals and physical models to prompt prior knowledge, color coding to emphasize importance or differences (anchor charts, sentence stems, paragraph frames, differentiating place value of multi-digit numbers), structuring purposeful discourse, and modeling thinking out loud.

Multi-sensory approaches to supporting students in acquiring language skills are often very effective. However, a caution is not to use too many different approaches at the same time or use strategies or tools that cannot easily be transferred to future learning. A cute visual of a pumpkin or cookie might not be as useful in developing the schema for paragraph or essay writing, or as clear as an anchor chart or paragraph frame using color coding and visual cues.

Scaffolding Strategies that Support

Language and Vocabulary Skills

at Different DOK Levels

DOK 2 – Paraphrase Passport

This strategy promotes active listening and speaking and builds language comprehension skills. This can be used when students work in pairs, such as to study together or to facilitate making connections in larger group discussions.

When a student wants to add information or make a comment, they must first paraphrase what the last person just said (“What I think I heard you say is ___”). Then the student can add to or extend the idea (I think this is important because ___” or “Another reason might be ___”). Since students are bringing in prior knowledge, making connections, or building on ideas of others, this strategy, is likely to elicit DOK 2 thinking.

DOK 3 – TBEAR

I’ve used the graphic organizer TBEAR for more than a decade at many grade levels, with great success. TBEAR does more than ask students to simply write words/phrases in the graphic organizer without making connections among ideas or applying deeper analysis. TBEAR can be used to build vocabulary or as a pre-writing or discussion preparation activity.

TBEAR effortlessly scaffolds students to move from DOK 1 to DOK 2, 3, or 4 and “T-B-E-A-R” makes it easy to remember what each part stands for:

T: Write a Topic sentence/Thesis statement/or claim (DOK 1); or define a vocabulary Term or concept.

B: Briefly summarize the text as a Bridge to evidence (DOK 2); or paraphrase the meaning in your own words.

E: Locate text Evidence/Examples (DOK 2); or provide both examples and non-examples when defining domain-specific terms.

A: Analyze every example/each piece of text evidence; Add more information to elaborate or to say why the evidence supports the thesis/claim (DOK 3).

R: State something to Remember (DOK 1 or 2) or a Reflection that may go beyond DOK 3 to DOK 4 (e.g., text-to-world connections, personal connections, connection to other sources).

Scaffolding for All

Equity begins with the belief that all students are capable of and need to move beyond simply memorizing routines and acquiring surface knowledge in a content area. This especially applies to students with learning disabilities and multilingual students.

Studies have shown that all learners need daily opportunities to use creative thinking, make sense of information and ideas, ask questions, engage in research and inquiry, and construct their own understandings through participating in substantive conversations.

Also see this popular Karin Hess article:

Six Ways to Add Rigor by Deepening Thinking

Although I am a retiree, I found this article interesting and valuable as I work with a second language student after school hours. I can see using TBEAR at many grade levels and it might work well with my student as well – grade 5.