Culturally & Historically Responsive Classrooms

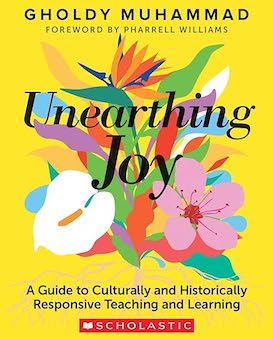

Unearthing Joy: A Guide to Culturally and Historically Responsive Teaching and Learning

By Gholdy Muhammad

(Scholastic, 2023 – Learn more)

Reviewed by Sarah Cooper

Even the look and feel of the book calls for delight. It’s bright yellow, with colorful flowers on the front, and the sections each have a different color margin:

Yellow for the Introduction: Watering the Earth With Educational Excellence

Green for Part I: Tilling the Soil: Preparing Ourselves for Growth

Chapter 1: Unearthing the Need for Genius and Joy

Chapter 2: Coming Into Joy

Chapter 3: Unearthing Self

Purple for Part II: Expanding Our Harvest: Putting Culturally and Historically Responsive Education Into Practice

Chapter 4: Redesigning Curriculum and Assessment

Chapter 5: Practical and Creative Uses of the HILL Model: Students, Teachers, and Staff Members

Chapter 6: Practical and Creative Uses of the HILL Model: School Leaders, Community Members, and Families

Chapter 7: Planting Seeds for the Future: Artistic Interpretations of the HILL Model

Finally, ten questions on the third page of each chapter encourage “unearthing” what we think about teaching and ourselves, asking: “Of all things in the world, what must you teach?” and “How (often) was joy centered in your teacher preparation, and now in your school or district?”

This book made me want to connect with my students by finding out more about their identities, backgrounds and passions. It made me feel once again that there is no nobler profession than teaching and that, as Muhammad says, “Education must be reserved for the brightest, most genius, and most conscious among us,” looking back for models toward Mary McLeod Bethune and Anna Julia Cooper, not simply Lev Vygotsky and Jean Piaget.

Most of all, Unearthing Joy reminded me that we must “put history and theory into action in classroom practices that are exhilarating for students, parents, educators, and all those working for diversity, equity and inclusion.”

The CHRE Framework

So how do we accomplish this cultural and historically responsive teaching most effectively? Not through guilt – “I have never encountered a historically responsive teacher who has made children feel guilty for something they didn’t do” – and not through despair and pain.

For instance, “You never start Jewish history (or others who have been oppressed) with what oppressors have done to them. You start the teaching with the histories, genius, and joys of the group of people before oppression, enslavement, or colonization. You tell the truth about their beauty.”

To tell this truth, we must start with genius, triumph and joy. Muhammad looks for historical inspiration toward an 1837 African-American newspaper that emphasized the importance of being a “reading person” and toward the “joy through formal academics” of the New York African Free School, which existed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

She also lays out an effective and immediately implementable framework using a few key terms. CRE denotes culturally relevant or responsive education, and CHRE adds a historical component, “emphasizing people and events that have traditionally been ignored or misrepresented in schools.”

In addition, throughout the book Muhammad frames lesson plans, unit approaches and even teacher evaluation and professional growth with five “pursuits” – Identity, Skills, Intellect, Criticality, and Joy. She situates these five elements within the HILL model, which aims to “respond to diverse students’ Histories, Identities, Literacies, and Liberation.”

Unearthing Joy gives dozens of examples of how to apply these principles to curricular planning, leadership and pedagogical conversation. Just one example: a unit about sugar, with this list followed by potential assessments:

1. Identity: Students will record and analyze their daily sugar intake and compare it to normed nutrition-related data.

2. Skills (Science and Disciplinary Literacy): Students will conduct an experiment to learn about the sugar molecule and sucrose, and learn how to dissolve sugar. Disciplinary Literacy: Students will learn to read and write a lab report.

3. Intellect: Students will learn the origins of sugar and where it is grown.

4. Criticality: Students will learn the harmful effects to the body of eating too much processed sugar.

5. Joy: Students will learn the benefits to the body of eating natural sugar.

According to the book, state standards tackle “only one-fifth of the culturally and historically responsive model: skills. They do not consider identity, intellect, criticality, and joy” (47).

Later on Muhammad gives suggestions for using the HILL model within classrooms, districts, or schools, including holding “Book Clubs of Professional Materials,” calling these gatherings “intellectual feasts” that can go beyond written texts to multiple modes of communication.

She also asks us to “Rethink Staff Meetings” by playing songs recommended by staff and posing questions such as “What do you do when, at the end of your day, you feel defeated?” and “How do you create spaces of joy for students?”

She also observes that curricular ideas can be found everywhere, inspired by “artists and artistry,” and can have “legacy” impact beyond the day-to-day of our classrooms. Next to the following quotation, I wrote OMG in the margin because I had never before thought of our curricular choices as so lasting:

“…what we teach and how we teach it must leave an imprint on the lives of our students. It should feel special and enduring…. Curriculum as legacy and legacy building should leave a stamp on our culture – and lead to a record of our times.”

Discover This Book’s Joy for Yourself!

This book must be read with intention – its playlists heard, its patterns colored, its suggestions considered, its questions reflected on – for it to settle in thoroughly and affect our practice. I marked innumerable possibilities that I want to use this year in introductory student surveys, in department and staff meetings, and for my own well-being as a history teacher and administrator.

Ultimately, this book demands that we see ourselves as context givers and creative wellsprings for our students. It also recognizes that we are enough, even when we feel we are not: “When you are tired and overwhelmed as you cultivate (and water) the next generations, please remember to claim and reclaim your joy over and over again.”

We are sufficient, and we must promote a culture of abundance rather than scarcity in education, because, as Gholdy ends the book, “there is enough for everyone.”

Sarah Cooper teaches eighth-grade U.S. History and is Associate Head of School at Flintridge Prep in La Canada, California, where she has also taught English Language Arts. Sarah is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom (Routledge, 2017). She presents at conferences and writes for a variety of educational sites. You can find all of Sarah’s writing at sarahjcooper.com.