Getting to Know Students Can Deepen the Learning

A MiddleWeb Blog

One treasure – Zaretta Hammond’s Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students – is full of useful information and research. I decided to jot down all the strategies that I wanted to try, and to take note of each strategy’s eventual impact.

Strategy One: Collect Data

One idea I tried was to choose a representative, focal student and collect data on my interactions with them over a few weeks. The book provided a collection tool I could replicate, but I ended up just using a notebook.

I was attracted to the idea of choosing a student with whom I would like to have a better relationship and who could represent other similar students. For me, these are often the reserved students who are hesitant to participate. After gathering and analyzing the data, I planned to set a goal for a change that would improve our relationship.

Results: The truth is, it felt uncomfortable (even a little creepy) to take notes on my students, and I abandoned the note-taking pretty quickly. But it did inspire me to spend more time chatting with my representative student. I tried to make a point of referring back to what we had previously discussed so the student knew I was listening.

While the student’s behavior in class has not changed greatly, she greets me first in the hallway and often comes to class a few minutes early to chat and check in. She was excited to tell me about the new after-school activities she was signed up for, which would not have happened at the beginning of the year. These are all positive signs indicated on Hammond’s “Rapport Interaction Task Sheet” included in the book.

Strategy Two: Kid-watching

Hammond suggests choosing 3-5 students to watch over the course of the week and take notes about. This reminded me of some advice attributed to Donald Graves (and mangled by my memory): you are not ready to teach a child until you know 10 things about her life outside of school.

This can be daunting when you teach over 100 students, but everything matters: siblings, extracurricular activities, who their friends are, etc. Look for clues on their laptop stickers, who they hang out with in the hallways, and what clubs they join. Then talk to them about what you know so that they know you care.

Results: Again, the note-taking didn’t feel right to me. But I did ask my students to tell me the after-school activities that they enjoy. With this information, I made sure that I attended a drama production, a choir concert and a rock band performance, and that I stopped by a robotics competition.

The next step is to get to the sports games. Another area for bonding was around Taylor Swift; my school hosted a screening of the Eras Tour movie for faculty. I attended and had a great time. After the screening, I noticed Taylor Swift stickers, water bottles, tote bags, etc. everywhere! It was such a great entry point for discussion, and students loved that I had beaded friendship bracelets that I had swapped at the show.

Hammond writes, “The brain is wired to scan continuously for social and physical threats, except when we are in positive relationships. The oxytocin positive relationships trigger helps the amygdala stay calm so the prefrontal cortex can focus on higher order thinking and learning.” This is definitely my favorite strategy, as it was fun and an easy way to develop the habit of bonding with students, while priming their brains to learn.

Strategy Three: Give time to process

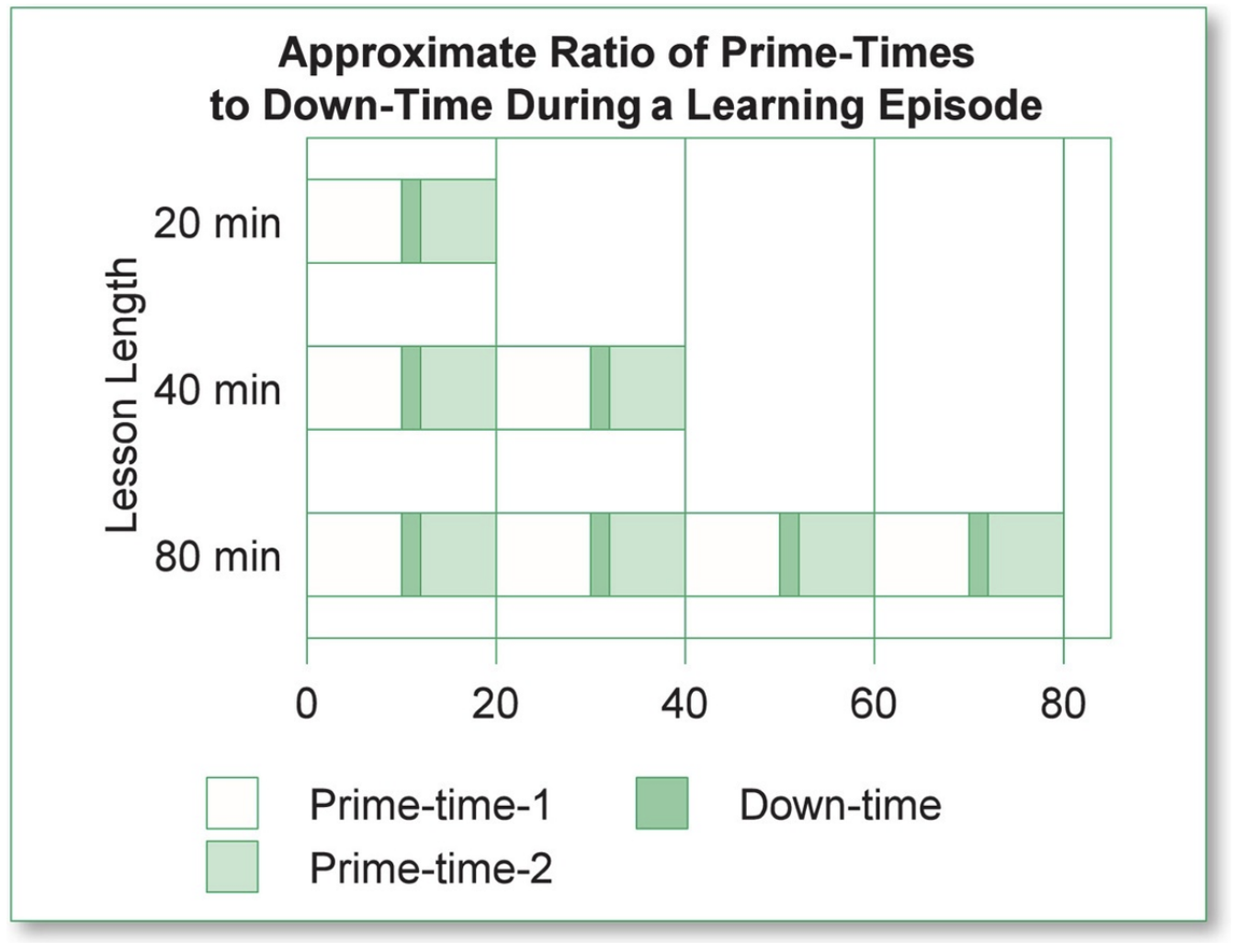

Hammond quotes information from David A. Sousa’s book, How the Brain Learns, about how the brain needs to periodically go into ‘consolidation mode’ to process new information. This led me to read his book, which has a valuable chart for teachers on a block schedule. My sixth graders’ classes are 80 minutes long, so I was eager to take in the advice.

Source: How the Brain Learns by David A. Sousa

Sousa recommends breaking the class into four 20-minute segments, which is something I already try to do, but he also recommends a short off-task break every ten minutes. This could be telling a joke or a story, playing music, or moving their bodies. I usually incorporate a brain break halfway through the class, so this would be a shift in practice.

Results: I tried taking a break or shifting activities every ten minutes on a day when my coach was observing my classes. She asked the students how the pace worked for them, and they were happy with the changes. For me, it felt like we could never dig in deeply to anything, so I will continue to work on this so that we can find a depth/break balance.

A recommended example from the text was to have students process in writing or drawing their response to the prompt, “What was the muddiest (lesson) point you are trying to make sense of?” This would keep their minds in the content we are tackling, while still giving them the needed consolidation time.

I am appreciative of the improved relationships that I have with my students thanks to Hammond’s book. I’ve always known that relationships come first when it comes to learning, and now I have some insight into the science behind why it is so important.

Very insightful post. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Chris!