History: Pairing Primary Sources and the Arts

By Jennifer Bogard and Lisa Donovan

Primary sources are the raw materials of history – original documents and objects that were created at the time under study. They are different from secondary sources, accounts that retell, analyze, or interpret events, usually at a distance of time or place. (Library of Congress)

Teaching through the arts provides authentic differentiated learning for every student in the classroom. (Bogard & Donovan, 2022, p.8)

A browse through the Library of Congress Classroom Materials reveals a treasure trove for middle grades history educators who want to deepen their everyday lessons by exploring primary sources through the arts.

The Library of Congress website includes a blog full of ideas, text sets of primary sources across social studies topics, and professional development programs for integrating primary sources into the classroom.

We find that pairing the arts with primary sources creates an opportunity to engage with a variety of perspectives, humanizing history and increasing personal relevance for students. With a click of each link, educators will find a rich archive of oral histories, photographs, speeches, and more, all related to curriculum topics.

The Library of Congress website explains:

Primary sources help students relate in a personal way to events of the past and promote a deeper understanding of history as a series of human events. Because primary sources are incomplete snippets of history, each one represents a mystery that students can only explore further by finding new pieces of evidence.

As educators who integrate the arts into everyday lessons, we turn to these resources time and time again and bring history to life through innovative arts exploration. We’ll show you how to do this in your own classroom.

Below are three ways to pair primary sources from the Library of Congress (including a letter, a photograph, and a political cartoon) with research-based strategies in the arts.

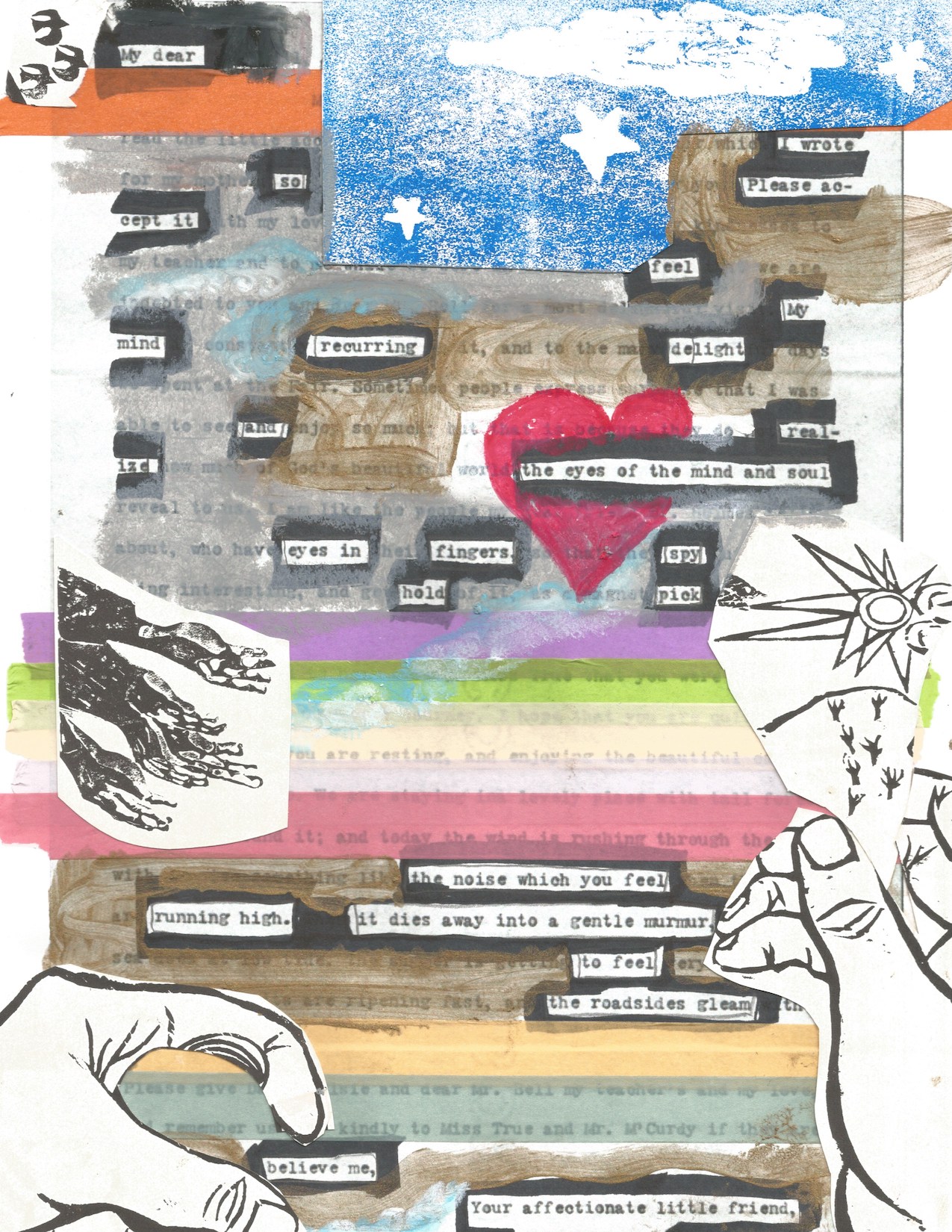

1. Transformation: Using the Altered Text Strategy with a Primary Source Letter

Artwork by Christine Flood using Helen Keller’s 1893 Letter from the Library of Congress

What is Altered Text?

When using the altered text strategy with primary sources, students are invited to engage deeply with historic materials such as letters, images, posters, and other documentary sources.

Students work with a variety of materials to explore, distill and translate historical ideas. In the process the appearance of the materials is altered as the interpretation of meaning is explored and constructed.

Primary sources are often pieces of a larger story, requiring students to use analytical skills to make sense of the context. Exploring the relationship between words and image can bring new insights and foster a sense of relevance for students.

Sanchez and Anderberg, et.al., (2017, p.24) explain that using the altered text strategy “allows participants to enter a text first, and make a deep connection with it personally, prior to having to engage in any other kind of analysis…The important part of this is that it offers an anxiety-free opportunity to create a completed artwork. It also builds the capacity for participants to connect with the words of others.”

Students can draw images over text; select words to emphasize through graphic elements; or lay color over words or phrases through paint, collage, oil pastels, or other visual materials. The source becomes a work of art giving context, revealing new insights, tapping into prior knowledge, and developing new understanding.

A quick web image search will reveal many examples to inspire and generate ideas.

Looking Into the Process:

Arts Educator Christine Flood used an altered text approach (above) with the Letter from Helen Keller to Mabel Hubbard Bell, August 20, 1893, a primary source document. Using the elements of artistic literacy (visual art) she worked with line, shape, and color to include illustration in conversation with the text, highlighting key ideas. Flood reflected on her process of working with the text and adding visual elements:

I was really moved by the way Helen explained her experience in this letter. I started by reading through the letter and with a pencil circling my favorite words that spoke to what she was trying to say, like “eyes in her fingers” and “the noise which you feel.” Once I had some words picked that spoke to my emotions, I then went back through and started composing a poem by choosing other words. My next step was to make my choices more permanent by using a bold marker to surround the words and make them stand out.

The feelings that overcame me in reading the letter [were] of happiness, joy, and hope so I wanted to express that in my art choices. I started blocking out text with colorful washi tape. Then I found images of sky, sun, birds, and most importantly hands. I wanted to focus on natural elements that one could hear and feel, not just see. I collaged them over and around text. I wanted to help Helen convey the message that her fingers were not just used to feel physical objects, but were used to feel emotions, feel time, feel life. Her hands let her see the world and she wanted to share this beautiful discovery. I finished blocking out text with paint and oil pastels, experimenting with different brushstrokes, and layering of colors and textures. (Bogard & Donovan, 2022, pg.199).

Students can also create found poems as part of the process. The following poem emerged for Flood, from the altered text above.

2. Creating a Soundscape Inspired by a Primary Source Photograph

What is a Soundscape?

We think it’s helpful to start learning about soundscapes by experiencing a sample. For an example from process to finish, visit this YouTube video [https://youtu.be/n-8P2Sey-es?feature=shared] from the Arts Integrated Curriculum at Brainworks.

By working with a primary source that depicts a historical event, we invite students to imagine the sounds that might be encountered as part of a moment in time. Taking time to imagine what might be heard, students can identify and list potential sounds. They can then explore ways to create a soundscape, a backdrop of sound that brings the moment to life.

We guide students in exploring sounds that can be created using everyday objects such as crumpling paper, shuffling feet, muffled voices, etc. Composing a soundscape can help to tell the story of a particular scene, creating a felt sense of what it might have been like to be there.

As soundscapes are shared, the listeners will experience being immersed in the event. Even a short soundscape can evoke a time, place, and sense of ambiance or political atmosphere and more.

Being mindful of basic elements of music such as dynamics, tempo, rhythm, pitch, texture, tone color, and so on, can ensure the soundscape is more accurate.

Looking into the Process:

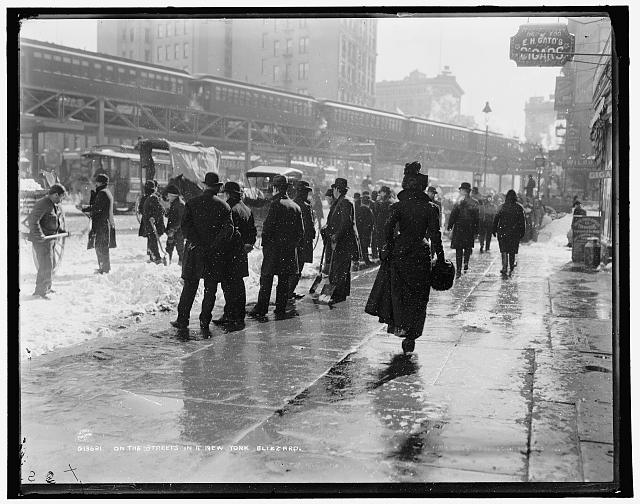

On the Streets in a New York Blizzard (above) is a primary source photo from 1899 in New York City.

We invited students to imagine how they might explore the photograph through sounds that come to mind.

Here are some ideas they imagined after examining the image, drawing on what they knew about aspects of the scene, and constructing new knowledge about the scene.

- crunching feet in the snow

- screeching of brakes

- blowing of a train whistle

- talking

- stomping of horse hooves on the streets

- rattling of carriages

These sounds can be made in the classroom through “found sounds,” using objects around the room (scrunching newspapers, tapping pens, etc.)

You might brainstorm ideas for found sounds that could be used to bring the image to life, similar to a soundtrack for a movie. We suggest using the elements of artistic literacy (music) to create a composition that brings the image to life through sound.

To learn more about the step-by-step process, planning questions, discussion questions, grade level suggestions, and assessment, view the full Soundscape lesson from Integrating the Arts in Social Studies: 30 Strategies to Create Dynamic Lessons (Bogard & Creegan-Quinquis, 2022, pgs.147-152).

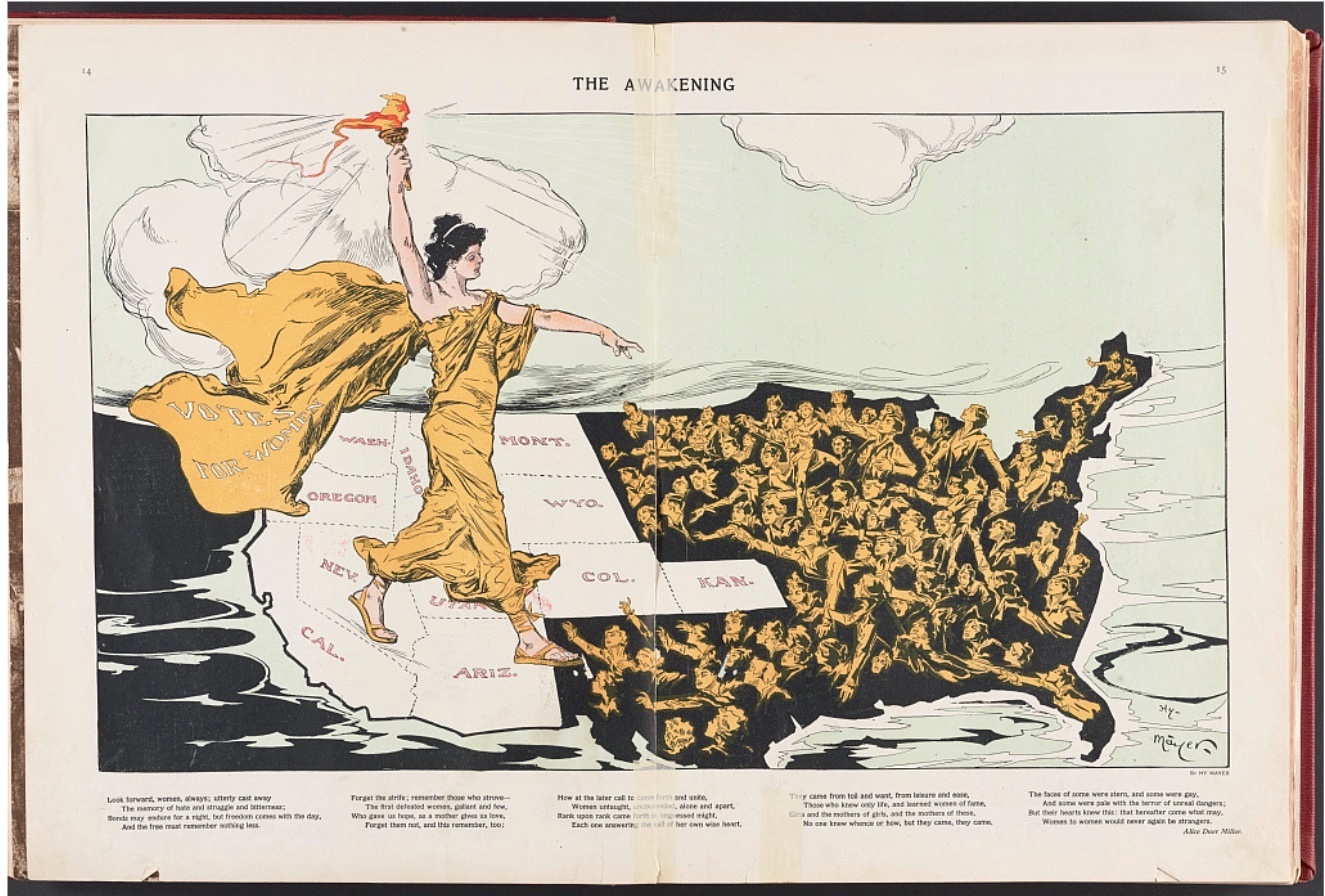

3. Sketching to Observe and Engage with a Primary Source

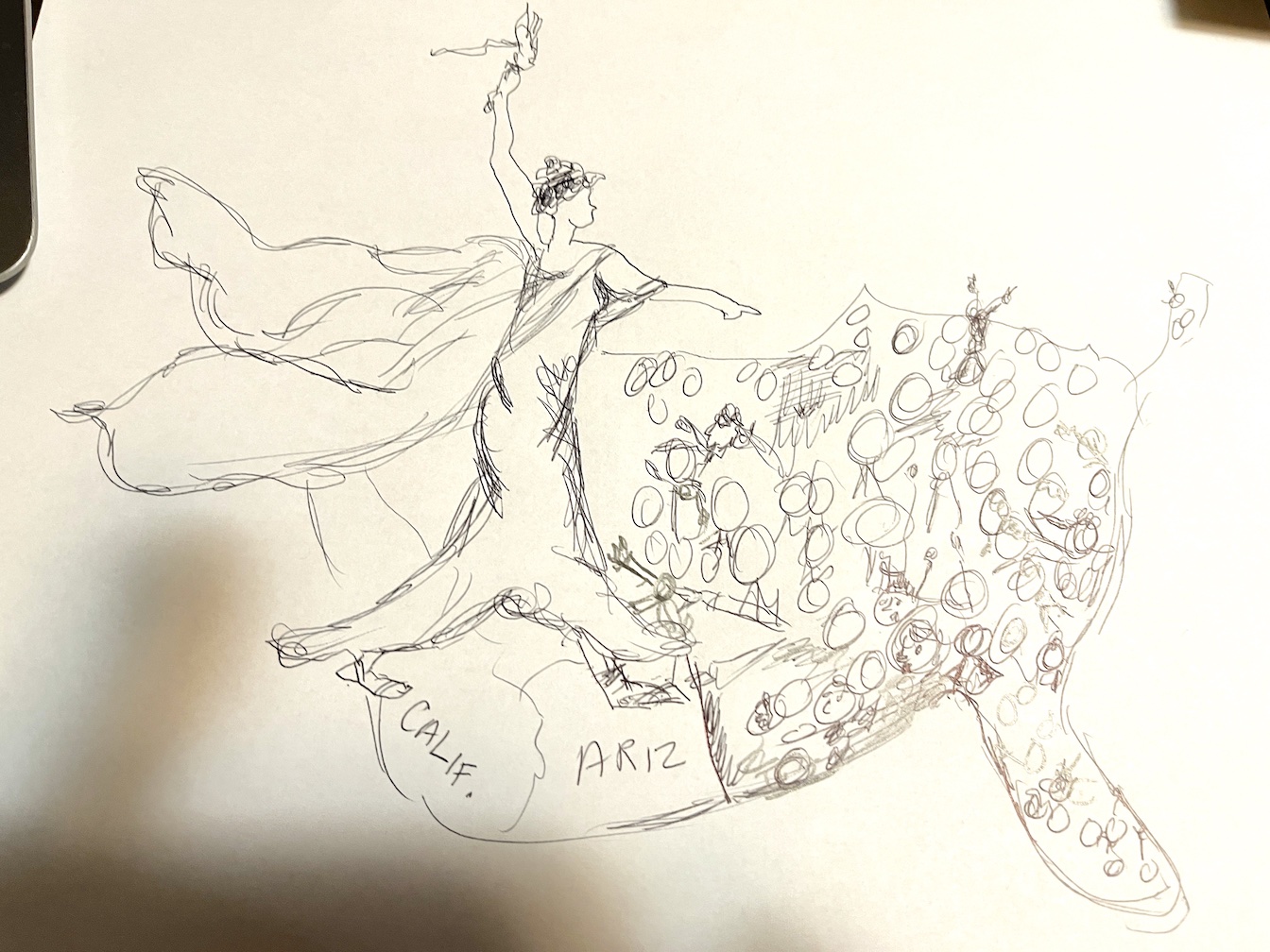

Here a sketch of the image The Awakening, retrievable here, brings the following reflection:

The Statue of Liberty has come to life and is striding forward with confidence, dress whipping around legs showing movement, determination, and purpose. One arm reaches high, clutching a flame, a beacon for others to come forth. The other arm reaches out, beckoning the mass of women suffering oppression to come forward…to join the movement…A call for justice.

What is Sketching to Observe?

Inviting students to draw what they see provides an active way to engage with a primary source. Students slow down, study the image or object they are viewing, and visually catalog their noticings as they sketch details.

We encourage students to begin by zooming in on particular areas of interest and sketch that one area rather than tackling the full image. It is less about representing the object or image, and more an exercise in close observation. This eliminates students’ concern with making an accurate picture and rather invites the lens of an historian.

Looking into the Process:

Arts Educator Tom Lee leads professional development workshops with a team from the Yale Center for British Art. A bedrock principle of their work is that drawing is prewriting. Lee shares his insight:

Students always show things in their sketches that they don’t initially include in their writing. There is nothing accidental. There is intentionality and meaning in every line of their drawings. Scan the students’ work thoroughly. Ask the student about any seemingly random marks to see what they reveal about the student’s thinking. Listen while they tell you about it, repeat it back to them, and invite them to expand their writing with the language they’ve used. (personal communication, April 12, 2021).

We encourage teachers to visit the online archives of the Library of Congress for protest posters from different time periods and invite students to focus in on a particular area of a poster and sketch to observe, documenting noticings, questions, and insights. It’s helpful to include a discussion of the elements of artistic literacy (visual art) in order to convey or amplify a message.

Hetland et. al. define observe as “learning to attend to visual contexts more closely than ordinary ‘looking’ requires, and thereby to see things that otherwise might not be seen” (2007).

To learn more about the step-by-step process, planning questions, discussion questions, grade level suggestions, and assessment, view the full Sketching to Observe lesson from Integrating the Arts in Social Studies: 30 Strategies to Create Dynamic Lessons (Bogard & Creegan-Quinquis, 2022, pgs. 174-179).

As you look for ways to bolster student engagement with history and primary sources, try these three arts-integration strategies: altered text; soundscape; and sketching to observe. Let us know how your lessons unfold.

Authors’ Note: The 2nd edition of the Integrating the Arts Series published by Shell Education features a wide variety of flexible strategies that can be used across grade levels and content areas. In this article, we drew lessons from two texts in the series: Integrating the Arts in Language Arts: 30 Strategies to Create Dynamic Lessons (Bogard & Donovan, 2022) and Integrating the Arts in Social Studies: 30 Strategies to Create Dynamic Lessons (Bogard & Creegan-Quinquis, 2022).

Download the References for This Article Here

Jenn writes books for children, including The ABCs of Plum Island, Massachusetts, described by Kirkus Reviews as “An unexpectedly soulful and absorbing chronicle of regional history in a scrapbook-style work.” You can reach her at her website, JennBogard.com, on Linkedin at Jennifer Bogard, Ph.D., and on Instagram @theabcsofplum.

Lisa served as co-director of the Berkshire Regional Arts Integration Network (BRAINworks) and as Director of the Creative Compact for Collaborative Collective Impact (C4), and director of the MCLA Institute for the Arts and Humanities. She is editor and coauthor of a five-book series on arts integration through Shell Education and co-author of Teacher as Curator: Formative Assessment and Arts-Based Strategies. She is also a TEDx presenter and the 2021 Recipient of the Massachusetts Arts|Learning Irene Buck Service to Arts Education Award.

This is a treasure trove for history teachers! .Jennifer & Lisa, thank you for sharing. I will be passing this article along to some of the social studies teachers I work with.

Hi Sharon, we’re so glad! We have another article with some additional ideas and resources, too: https://www.middleweb.com/49226/integrating-arts-in-ela-creating-2-voice-poems/

Thanks again for your feedback! Jenn Bogard