The Year I Figured Out Student Self Assessment

By Stephanie Farley

The topic of grading and assessment is a deep well for me. I was an English teacher in a classroom for 26 years, and in each of those years I changed at least one aspect of my assessment/grading practice.

The topic of grading and assessment is a deep well for me. I was an English teacher in a classroom for 26 years, and in each of those years I changed at least one aspect of my assessment/grading practice.

In year 21, I finally nailed an approach that had eluded me for two decades: students successfully, meaningfully, and joyfully evaluating their own work.

Let me be clear…my early attempts at student self-assessment were woefully misguided and entirely inadequate. I gave vocabulary and grammar quizzes and had students correct them. Not only was this a ridiculous practice, it was a distinct failure (eventually, I stopped giving vocabulary and grammar quizzes).

I also had students put together a tiny “portfolio” of journals and evaluate the portfolio. Miserable. I had students evaluate their own essays, without appropriate scaffolding or instruction. Epic fail!

I knew that these approaches failed because:

1. The kids didn’t understand why I was asking them to evaluate themselves, and I couldn’t properly articulate why. Truthfully, at the time, I think I was overwhelmed by paperwork.

2. The self-assessment attempts didn’t improve subsequent performance.

3. The students and I both felt a little cranky and dispirited afterwards.

A further confession: I did not start teaching with a solid background in education. Rather, at university I studied adolescent psychology and English literature, so as a new teacher I didn’t have the tools to craft an effective grading/assessment protocol.

But, by my 21st year, I had taken so many classes and so thoroughly immersed myself in the educational literature and research – and, frankly, was so rich in failure! – that I was able to see a path forward.

The changes I made that year were transformational…the best I’d ever managed. My students were markedly calmer, happier, and focused. That calm and focus was reflected in their academic performance, their behavior in class, and in student evaluations. It was the beginning of the best teaching of my career.

If I were to boil down the most essential change I made – the one that made a significant difference in outcomes – it was this: I asked students to explain their thinking.

It sounds simple, and it is! Here’s my process:

1. Before students started a writing project, I’d ask them to identify which of 3 learning targets they were going to focus on in the project (roughly, these were big idea, details, and mechanics).

2. Students wrote at least two to three versions of their projects, getting scaffolded feedback from peers along the way.

3. When students turned in their work to me, I made comments on the work (no grade attached) and asked students to make revisions.

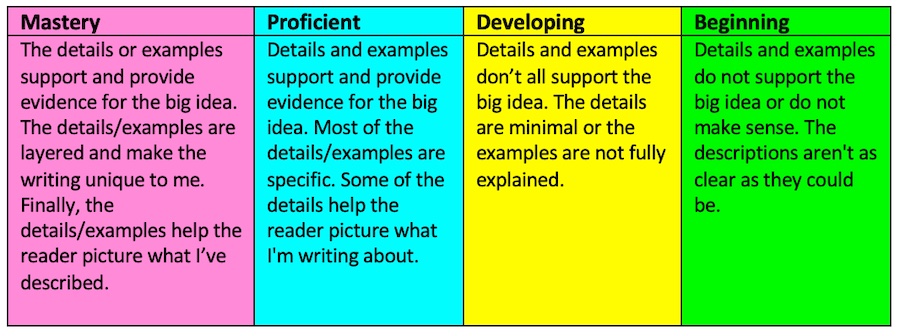

4. After the revisions were made, I asked students to evaluate their work on the rubric for the specific learning target on which they’d focused. Here’s an example of a learning target and its rubric:

I can explain my big idea using specific details or examples.

5. Then I met with each student to discuss the revisions and the grade. It was in these conferences that I asked students to explain their thinking. The first level of explanation was in showing me their revisions and indicating why they’d made those choices. The second level of explanation was showing me their own evaluation of the work and backing up their evaluation with specific references to their writing.

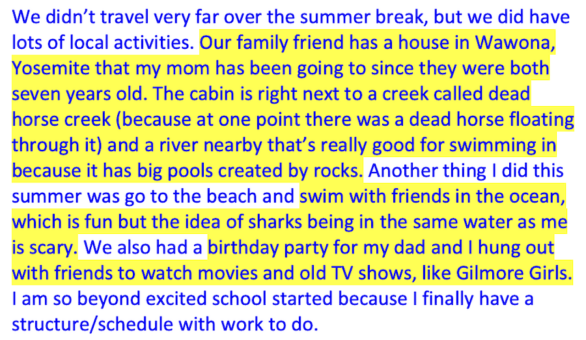

For example, if a student felt they’d achieved at a “mastery” level on “details,” they’d highlight their project to indicate those details that met the rubric criteria. Here’s an excerpt of student writing, highlighted to indicate the details they felt they included (from an assignment to write a story in six sentences).

Meetings powered by students

One of the reasons these meetings were effective is because students were the engine at every step: they decided what to focus on as they wrote, they made decisions about how best to demonstrate their understanding of the learning target, and finally they used the rubric and the evidence in their work to evaluate their performance.

There’s another reason having students explain their thinking was transformative. In effect, students were teaching me about their work. Teaching others is like a superhighway to understanding. For instance, I did not deeply understand grammar until I had to teach it. Similarly, students did not deeply understand why they were making certain choices in their writing until they had to explain those choices to me and evaluate the work product themselves.

Reaping the rewards of all this work

Once I gave up responsibility for “explanation,” especially as it related to grades, my students were far less anxious and far more confident. In fact, they had the confidence that only comes from competence in a given endeavor. And, it turns out, competence is highly motivating!

You know that swagger that some kids have when they’re really good at something? By the spring of each year, the majority of my students rocked into class with that telltale swagger, because they felt good about their work and knew that each day of English class would allow them to grow their skills just a little bit more. They had earned their confidence.

In this new year, as you think about how to motivate your students through the short, dark days that lead up to the next break, I encourage you to try just this one thing: ask students to explain their thinking. You’ll likely be pleased with the results.

Stephanie’s first book is Joyful Learning: Tools to Infuse Your 6-12 Classroom with Meaning, Relevance, and Fun (Routledge/Eye On Education, 2023). She has created professional development for schools around reading and curriculum and coaches teachers in instruction, lesson planning, feedback, and assessment. Visit her website Joyful Learning and find her other MiddleWeb articles here.