5 Fun, Ethical Uses of AI I’ve Shared with Students

By Sarah Cooper

Earlier this school year, I laughed at myself while making copies in the faculty room. For an assignment that would end up being a one-page letter to a politician, I had created a 12-page directions packet. 12 pages!

Earlier this school year, I laughed at myself while making copies in the faculty room. For an assignment that would end up being a one-page letter to a politician, I had created a 12-page directions packet. 12 pages!

Admittedly, I tend to over-scaffold, especially with research projects, because I want students to work independently while being able to ask questions. However, in previous years this assignment’s directions had been half the length.

In our era of AI large language models (LLMs), though, I had included not just a model, directions and rubric, but also two pages of “Research Process Steps,” two pages of “Writing Steps: How to Put Together Your Letter,” and one page on “How Can I Use ChatGPT, Bing, Snapchat or Other Generative AI for This Letter?” (The short answer to that last page: make sure you have parental permission, and then try finding people to write to, while checking behind the AI to make sure the people it suggests exist and are still holding office.)

My eighth-grade U.S. History & Civics students spent two periods doing research and then two periods writing in class. Students shared their Google Doc with me from the start. Happily, when they submitted their rough draft letters on topics from sustainability to homelessness, the letters were generally “in their own voice,” as the rubric said (with a few exceptions from what turned out to be overwrought Grammarly interventions).

Ultimately, the letters were the best I’ve seen, partly because of the specific directions that encouraged students to add more concrete details and commentary. I’m proud to see our bulletin board with everyone’s work on it, and I’m hoping we hear back soon from the recipients.

But this writing and research assignment, along with others since ChatGPT beamed into our computers in December 2022, has made me wonder: Does the future of authentic writing in school mean painfully intricate instructions, a shared Google Doc, and lots of in-class writing time? And what does developing students’ writing voices even mean in the AI era?

Fun and Helpful Uses of AI So Far in Class

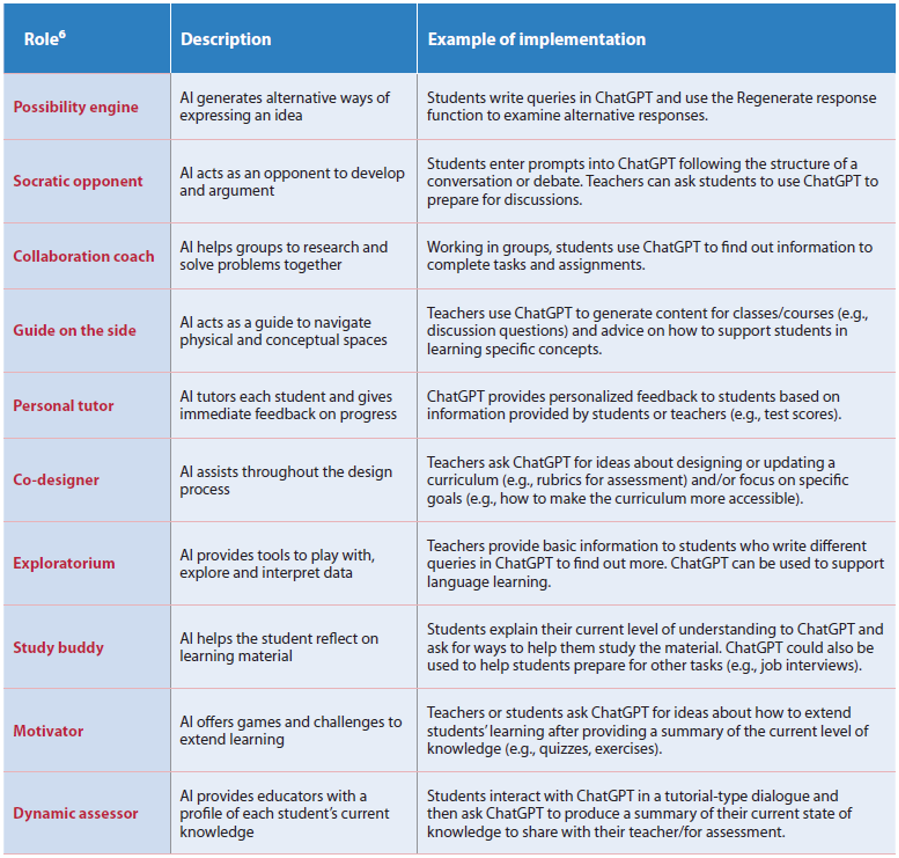

Over the past year my students and I have played and experimented with AI. Its well-documented pedagogical uses for brainstorming, self-tutoring, summarizing, and making conceptual connections have sparked creativity and agency, as outlined in this chart from UNESCO’s “ChatGPT and Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education” (p. 9, 2023):

For each major assignment, I’ve given a suggestion for a fun and ethical use of AI, and I’m always open to suggestions from students as well.

►1. Illustrated Quotes: For an illustrated quotation relating to a community impact project, students use Canva for AI image generation and ChatGPT or Bing AI Chat for finding quotations (double-checked for accuracy through Google).

►2. Primary Source Research: For a reformers research project, students go to LLMs to find quotations from primary sources on the free web. It’s helpful to ask the chatbot to give a link to the specific source from which the quote was taken (then check the link!).

►3. Book Covers: For the same project, students put their research paper into Dall-E or another AI illustrator to create a cool book cover (keeping in mind text generation in AI images is still a little wonky).

►4. Current Events Summary Draft: For a quarterly current events presentation, students can use AI to distill the main points of a news article before putting the summary in their own words. The jury is still out for me on whether this is truly a learning moment for them, and I also realize that students can put their own writing into AI language models and get a summary in their own style.

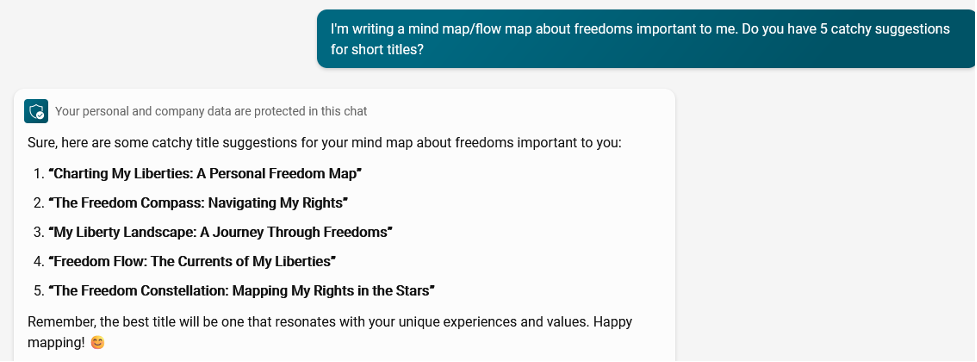

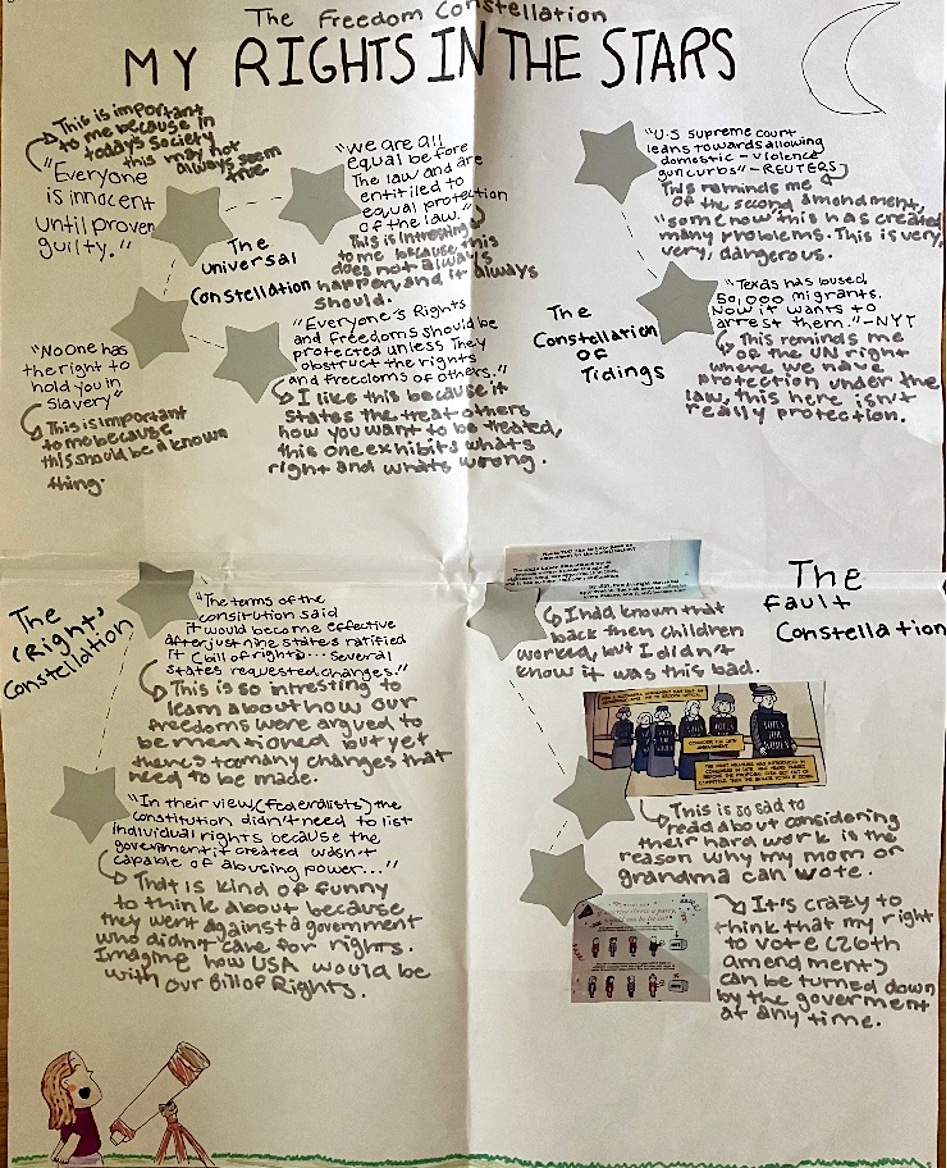

►5. Slogans and Titles: ChatGPT and other LLMs excel at creating headlines, tag lines, slogans, mottos and more. For a public service announcement video project this year on following the news, one group found the slogan “News Connects, Community Reflects” on Snapchat’s AI. For a midterm flow map assignment, a number of students used AI’s title suggestions (click below) to drive their graphical interpretations of the material we had covered this semester, with conceptually deep results.

Questions I’m Still Puzzling Through

Turning to academic integrity, recent research from Stanford published in the New York Times said that the percentage of students who “said they had recently engaged in cheating” has not changed since the advent of ChatGPT, remaining at 60 to 70 percent. Even so, as a teacher it’s clear that the quality, if not the quantity, of plagiarism has shot up.

However, focusing too much on plagiarism will mire us in a losing battle in the present. More interesting and relevant to me are questions on how the nature of learning and teaching is evolving to meet our current technological moment and our students’ needs in the future, such as:

Is the research paper defunct?

As a history and English teacher, I definitely hope not, because synthesizing and putting together ideas on the page develops thinking. However, I think we need to be open to the immense help that can come from students’ using AI to find material and brainstorm outlines. Such assistance can also prevent writer’s block and make students feel more capable when they do start typing.

What role does paraphrasing play in this new world?

This is one of the trickiest questions I struggle with. LLMs seem nearly perfect at paraphrasing and encapsulating information. Does it make sense for students to still know how to paraphrase? Do we want students to use AI to summarize a document and then incorporate the summaries (cited, of course) in their own work? Will paraphrasing soon go the way of doing bibliographic citations by hand?

What about annotating?

Actually, annotating seems more important to me than ever in order to show student thinking on the page. This year I shifted weekly current events assignments from a short summary with bullet points to 6+ annotations over two pages of an article. Most students do these annotations through Google Docs, and their insights are far longer and deeper than when they did them on paper in the past. So far, this is a win for me in terms of the student thinking process.

Which writing skills are important?

We can always ask ChatGPT to create an essay and then compare it to a human essay to see the spark that (at least for now) appears more often in the best human-written essays than the best AI ones. This popular compare/contrast activity teaches the skill of discernment, important in an AI age.

But in terms of writing itself, it seems still crucial for students to spread their mind across the page, to puzzle through ideas, to discover how they think so that they can understand how others put together arguments. And to achieve this, we need to create space and structure in which students think on their own.

2024 and Beyond

I’m still a little sheepish about my 12 pages of directions, and I might cut some of the steps next year to give more flexibility within the structure of the letter to a politician. At the same time, within that long packet I also see promise for my continuing experimental relationship with AI:

● Listening to how students want to use these powerful tools and then incorporating their strategies into future assignments.

● Requiring annotations of documents and articles as a basis for research and writing.

● Caring about who students are. I can’t count how many times I’ve said to “write this in your own voice” this year. I want to hear these young adolescents’ perspectives because each of their outlooks is truly individual and is affecting our world already.

On that note, here are some sentences in eighth graders’ own voices from the final drafts of their letters to politicians:

● As someone who has never been in the shoes of disabled athletes, I want to emotionally connect to them and get a glimpse into their lives, especially through sports, one of my many passions.

● As a young, queer person, I find it crucial to provide a space where the mental health of LGBTQ+ youth is protected and valued.

● When I was in elementary school, I was in need of a tutor because I was falling behind in class. This tutor changed my life completely and not only made me thrive in class but become more confident in myself as a student and a person.

Even as I’m not sure quite where we are going with AI, I can’t wait to keep following its developments, together with my students, this semester and in years to come.

Sarah Cooper teaches eighth-grade U.S. History and is Associate Head of School at Flintridge Prep in La Canada, California, where she has also taught English Language Arts. Sarah is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom (Routledge, 2017). She presents at conferences and writes for a variety of educational sites. You can find all of Sarah’s writing at sarahjcooper.com.

This was a great article! I loved reading about how you’ve successfully (and ethically!) used AI with your students. The 12 pages of directions made me LOL…I get it! I especially appreciated seeing the student work and the “questions I’m still puzzling through” section. Your frank discussion of the points about AI that make you wonder make me go, “Yeah! What ABOUT annotating?!” At any rate, thanks for sharing this journey, Sarah. It’s really instructive.

Stephanie, thanks for your kind words and for puzzling through the journey with me! I really appreciate thinking together with colleagues about these unprecedented questions.