Empowering Kids to Help Make School Decisions

If schools are always being “held” accountable, asks leadership coach and veteran principal Matt Renwick, how will students ever learn to “be” accountable? When do they get to make important decisions that affect others and themselves? Three shifts can change the paradigm, he says.

It was November 8, 2022: Election Day. As the polls opened at city hall, a lot was also happening within the library walls of Mineral Point (WI) Elementary School.

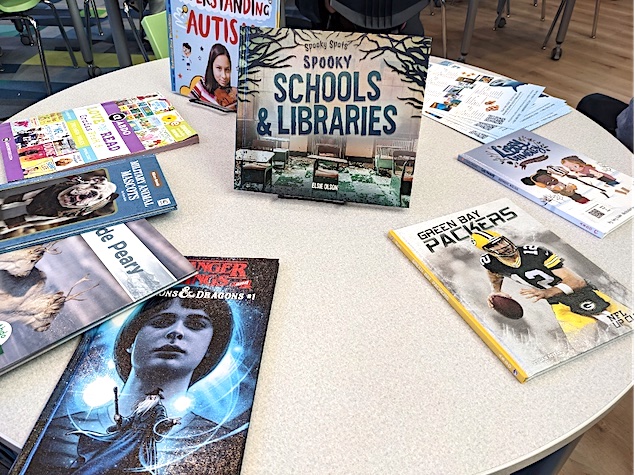

- In one half of the library, a group of upper elementary students were learning how to collect data using digital forms. Their purpose was to gather information about what their peers wanted in the library catalog and for the library space in general.

- In the other half, another group of students voted for which light fixture they’d like to purchase and install in a reading area. The three choices were previously determined by their peers across the way.

- Additional students were roaming the library, looking for that next book to read, on their own or guided by a friend.

As leaders of our school, observing the students fully engaged in their tasks, media specialist Micki Uppena and I wondered aloud:

- What would a school look like if the students made many more decisions?

- Would less constraints and more choice improve not just engagement but also academic and behavior outcomes?

- How much teaching could be reduced in favor of personal projects like this one?

- What would happen to all our curriculum resources?

As the citizens of Mineral Point exercised their right to vote, we started to imagine what a similar democratic experience might look like schoolwide.

When Students Own Their Learning

“Equity is action.” – Dr. Monique Darrisaw-Akil

One of the most pernicious problems in education is students’ lack of engagement in school.

Survey results tell us that schools bear some responsibility for these outcomes. It’s common knowledge that the longer U.S. students are in school, the greater decline in engagement levels (Calderon & Yu, 2017). Conversely, the more students feel engaged in their learning at school, the better their academic outcomes (Reckmeier, 2019).

Many systemwide responses to this challenge have shown little to no improvement, and these lackluster results have a direct impact on the equity issues we ultimately seek to resolve. If the responses devised by adults to the engagement problem are not working, where could we look for a better model?

Here’s an idea: what about looking to the kids themselves? We have seen the power of young people to influence policy makers and create real change in our systems.

- Greta Thunberg elevated the global conversation around environmental harm and well-being.

- Several Parkland High School students became a collective advocate for gun control.

- Malala Yousafzai won the Nobel Peace Prize for standing up for a female’s right to an education.

These young people seem to have at least two things in common: a deep purpose for their work, and the ability to engage in that work without teacher intervention.

While these examples are big, what if our strategy to increase engagement (and subsequently improve academic and equity outcomes) was to simply give our students more leeway in deciding what to learn, how to learn it, and what to do with the learning they accomplish?

During our own project – empowering upper elementary students to improve the school library – Micki and I discovered three shifts that schools can make to support young adolescents as self-directed and interdependent learners.

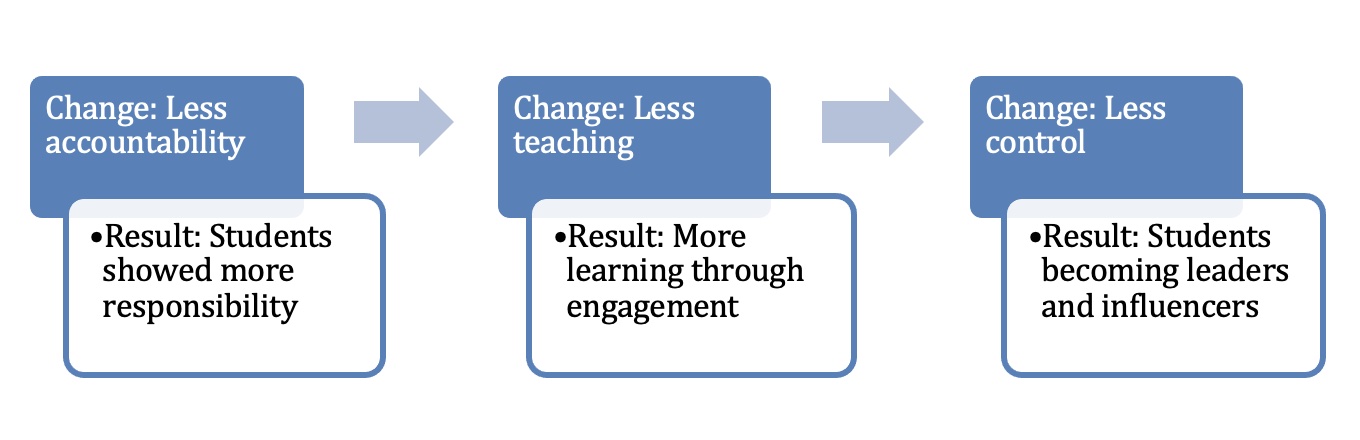

Shift #1 – From Accountability to Responsibility

One of the most common terms used in public education is accountability. It’s frequently referenced whenever questions come up around standards, testing, and teacher evaluation. While a desire for transparency is appropriate, the problem with accountability is two-fold.

First, many assessments used in schools don’t accurately represent the type of learning that people are looking for today. Flexibility, creativity, problem solving, and collaboration are some of the most prized qualities of employees and entrepreneurs. Yet they aren’t often taught or learned when the pressure is on teachers and leaders to ensure students do well on tests.

Second, if schools are always being “held” accountable, how will students ever learn to “be” accountable? When do they get to make important choices that affect others and themselves, key skills for a functional democracy? Giving young people the authority to make decisions needs no rationale beyond giving young people the authority to make decisions.

This led us to embrace responsibility, offering students enough knowledge and support to co-lead their own learning.

What we tried

In 2020, students were offered the opportunity to select and keep a new book from the library. Educational literature supports this innovation. Dorrell and Carroll (1980) found that when comic books were made available in a school library, the overall circulation rate increased by 30% due to increased visitors. Our goal was to use popular texts to gain students’ attention and then guide them toward related yet more complex texts.

- These new texts were similar to more popular titles but had a higher complexity level; they were placed in close proximity to each other.

- Prior to students coming to the library, book preview videos of these more complex texts were viewed in classrooms.

- Before and after students selected a book they wanted, Micki facilitated a conversation with each class about the purpose for this project and what they learned.

My role as principal was to take observational notes of what students did and said when they perused the selection.

What we learned

A major insight we learned was how engaged students were in the experience of the project in addition to simply getting a new book.

- Two students who wanted the same book were able to resolve this challenge. One of them had already scanned the entire setup and found two copies of the text. “If you want this one, you can get it. There’s one more, you know.”

- Another student asked Micki, “Are we going to do this every year?” She also confided that, even though she checks out a lot of books, she doesn’t actually read a lot. This example conveyed a sense of trust and safety in the space Micki had created.

- A group of boys decided to create a voluntary book club around a text on Greek mythology. Because there was only one copy of the book, the leader of the club came up with a plan to share the text through partner reading.

These outcomes around community and engagement were balanced with honest feedback from the students. For example, a few students announced there were no biographies available; they were currently studying important figures of history in their classrooms, and biographies interested them.

This feedback reminded Micki of another librarian who regularly gave kids similar responsibilities to decide how to spend the limited library funds for new books and resources. It also offered an entry point to highlight authors and texts from many backgrounds, titles that represented the student body and the world. It also seemed like a logical next step to the challenge students brought to us in this initial project – getting books they wanted in the library.

Shift #2 – From Teaching to Facilitating

In order to understand students’ needs, there must be a space for them to express their interests and ideas.

It goes beyond posting a book request list next to the classroom library. Although a good first step, we learned these invitations also need validation from peers and teachers for students to build confidence in their ideas.

Teaching in the traditional sense still has its place in the classroom, such as for building skills in which the teacher holds technical expertise. Yet when it comes to building knowledge for complex experiences like creating a more diverse and representative library, it’s essential that more voices – especially students’ – are heard and taken seriously. Their ideas and insights offer teachers entry points for making learning more relevant.

With this thinking in mind, 4th and 5th grade students were invited to co-lead the next school library text acquisition process. A major part of our professional goal was to move from a teacher’s mindset to an identity of a facilitator. It’s a shift from directing learners’ attention to the teacher to holding a structured space for everyone to learn from one another and leverage the power of the group.

What we tried

In the fall of the 2021-2022 school year, we announced open applications to join the “School Library Book Budget Project.”

A group of over 50 students signed up and committed to the project. After the vision of success was explained, three steps were co-developed to reach that vision.

- Examine the current selection of texts in the library.

- Position students as literacy leaders who ask their peers for their input.

- Reach consensus on how to represent the students’ interests, identities, and needs with the purchase of new texts.

Thanks to support from the nonprofit Bring Me a Book and from Title IV dollars, students were given authority to create a budget to purchase texts. They started by auditing the current state of the school library.

Micki provided a framework to guide students’ observations of the library catalog around specific elements, including:

- Cultural diversity and representation

- High-interest topics at various levels of readability

- Physical condition of books

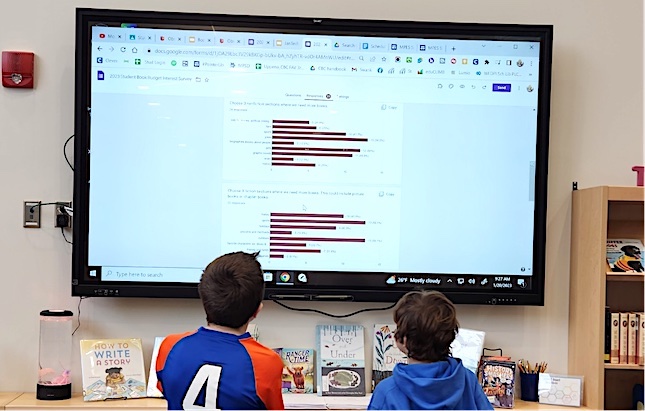

Student leaders also collected data from their peers about what they would like to see in the library. Equipped with tablets and shortcuts to the co-created digital forms, they roamed around the school, asking kids at every age to fill out their surveys.

Once observations and survey responses were organized, the students met in smaller groups to look for patterns and trends. Some insights surfaced:

- Replace “well-loved” copies

- More nonfiction titles for younger readers

- More graphic novels

- More books about disabilities and non-traditional family structures

In addition, the group took a field trip to an independent bookstore to learn more about book display and design. The bookstore staff were inviting, happy to answer the kids’ questions about the thinking behind the setup to promote sales. (We also pre-purchased books from them, demonstrating the importance of independent bookstores.)

With this information, the students were ready to meet with book distributors and publishers to learn about what titles were available for purchase.

What we learned

Coming into the project, we were aware of the influence that motivation (“a driver of human action,” Afflerbach, p. 24) and engagement (“the positive outcome of combining motivation and reading goals with strategies and skills; the state of students who are invested in reading, who give full attention to reading, and whose reading is marked by enthusiasm and forbearance,” p. 24-25) has on literacy experiences.

What was new for us was the complex nature of motivation and engagement. For instance, Micki overheard a girl confide to peers that “we should purchase a couple of books on ADHD, so that I can share them with my friends and they can understand what it’s like to be me.” This example led us to believe the book budget project wasn’t just about getting new books; there was a deeper mission when one student is able to see the unique importance of this work for themselves and others.

Would this type of event occur in a more traditional teaching experience, for example when the teacher is the center of knowledge and sole authority on what to learn and how? Facilitation releases some of that authority to support student discussion and decision making. Managed well, students feel safe to express their deeper needs as learners and as people.

Shift #3 – From Controlling to Trusting

After communicating with book distributors and publishers, the students found consensus on titles to purchase.

As the packages came in, Micki would announce a new shipment plus an invitation to participants for an “unboxing.” We recorded video of students opening up the delivery with smiles and eyes wide. These videos were shared online with the classrooms to notify everyone about the new arrivals.

Mornings before school officially began were spent cataloging, labeling, and positioning the books in a promising location. When there were no new books to process, students helped get the library set up for the school day, turning on the computers and other tasks. And if there was nothing to do, they simply read.

Embracing Collaborative Independence

Standing back and watching this unfold over the school year, we realized that our official roles as teacher and principal didn’t seem to fit nicely with the positions we are tasked to fulfill. This project called on us to embrace “collaborative independence” – defined by Johnston and colleagues as directing one’s own teaching and learning within a broader community that cultivates a safe environment for innovation and risk-taking (2020).

To support the success of the project, we had to let go of a desire to arrive at predetermined outcomes by controlling the experiences. The shifts we made is a story of becoming more comfortable with being uncomfortable in releasing authority and responsibility to students.

What does this research say to us regarding how we operate on a daily basis? A common interpretation is that we should do more teaching and leading, which can often lead to a more controlled and less engaging experience for kids.

Yet the results from the book budget project show the impact of trusting students as readers and leaders. On average, students who participated in the book budget project:

- Experienced a 17% increase in their reading proficiency scores, compared to a 4% increase for students who did not participate.

- Checked out 18 more books than non-participants.

- Demonstrated more positive perceptions about reading and stronger identities as readers.

In spite of these positive results, we still see challenges. Here is what we are currently wondering:

- What professional learning do educators need to support students as co-drivers of their own learning?

- How can teachers, leaders, and students take what they are learning and influence new communities?

- What needs to change within our curricula to support more opportunities for students to talk with and listen to one another around a common goal?

- What is needed to convey trust in students to make decisions on behalf of themselves, their peers, and the community?

We continue to explore these questions. You and your students can, too.

Tips for a Successful Student-Directed Project

- Start small. Making big long-term changes begins with a first successful step to build confidence and invite more questions.

- When thinking about a project, examine sources of tension in your context. Begin to question why a longstanding problem, such as students not taking risks as readers, has not yet been solved. This can lead to exploring potential responses that can disrupt the status quo. There is no equity without inquiry.

- Find a balance between creating goals and plans and supporting changes in direction as the project progresses.

- Trust is paramount. Let students feel the weight of responsibility as well as the elation of making a difference. Structure opportunities for kids to discuss these decisions and reflect on the outcomes.

- Collect data to support and validate the work. Letting kids lead their own learning will likely break some unwritten rules in your school, at least in some wings of the building.

References

Afflerbach, P. (2022). Teaching Readers (Not Reading): Moving Beyond Skills and Strategies to Reader-Focused Instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Calderon, V. J., & Yu, D. (2017). Student enthusiasm falls as high school graduation nears. Gallup, available: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/211631/student-enthusiasm-falls-high-school-graduation-nears.aspx.

Reckmeyer, M. (2019). Focus on Student Engagement for Better Academic Outcomes. Gallup, available: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/211631/student-enthusiasm-falls-high-school-graduation-nears.aspx.

Darrisaw-Akil, M. [@MDarrisawAkil]. (2022, September 19). Equity is action [Tweet]. X/Twitter. https://twitter.com/MDarrisawAkil/status/1571849741234831360

Dorrell, L., & Carroll, E. (1981). Spider-Man at the Library. School Library Journal, 27(10), 17-19.

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How Principals Affect Students and Schools. Wallace Foundation.

Johnston, P. et al (2020). Engaging Literate Minds: Developing Children’s Social, Emotional, and Intellectual Lives, K-3. Stenhouse.

Matt Renwick is a systems coach for an education service agency, CESA #3, in Fennimore, Wisconsin. Previously, he served as a principal in two Wisconsin elementary schools and as a former middle grades vice principal, teacher and coach. He is the author of Digital Portfolios in the Classroom: Showcasing and Assessing Student Work (ASCD, 2017) and Leading Like a C.O.A.C.H.: Five Strategies for Supporting Teaching and Learning (Corwin, 2022). Connect with Matt on X/Twitter @ReadByExample.

Micki Uppena is the library media technology specialist of Mineral Point Elementary School. In addition to Micki’s teaching responsibilities, she was president of the Wisconsin Educational Media & Technology Association. She also serves as a trustee on the Mineral Point Public Library board. Connect with Micki on X/Twitter @Mic_Uppena.