Shakespeare: A Rite of Passage for 6th Graders

By Jeny Randall

“Nay, faith, let not me play a woman. I have a beard coming.” (Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.2.45)

“Nay, faith, let not me play a woman. I have a beard coming.” (Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.2.45)

Adelina tosses the ball across the circle to Will who peers at a paper in his hand. “The course of true love never did run smooth.” (1.1.136)

Will tosses the ball to the next student who soldiers through her line, “My mistress with a monster is in love!” (3.2.6), and on the ball goes, back and forth across the circle. So begins our study of Shakespeare: with a tapas of lines from the play delivered without context or correction.

When I first taught this unit six years ago, I asked my students what came to mind when they heard the name “Shakespeare.” One student responded, “I think of death and Romeo and Juliet.” Another wrote, “A old time-y english guy who wrote plays in a very weird version of English.”

Since that time, the 6th grade Shakespeare unit has become a rite of passage, and students from years past check back fondly to track the unit’s progress.

How it all began

I was lucky. I read Macbeth as a 5th grade student and found myself on my feet acting out the part of Banquo. The following year, our 6th grade class took Midsummer Night’s Dream to the woods adjacent our school where, acting the role of Demetrius, I tried to shake Helena by hiding behind a particularly large tulip poplar.

So when a teacher friend referred me to Shakespeare Set Free (2006), I was sold. Three volumes provide a roadmap for “an innovative, performance-based approach to teaching Shakespeare” across seven of his most beloved plays.

The books are published by the Folger Shakespeare Library, an incredible resource for teaching and studying Shakespeare’s works.

In her introduction to volume one, editor Peggy O’Brien expands on the beliefs that provide the foundation for the series, including “Shakespeare is for all students: of all ability levels and reading levels, of every ethnic origin, in every kind of school,” and “Shakespeare study can and should be active, intellectual, energizing, and a pleasure for teacher and student.” (xii)

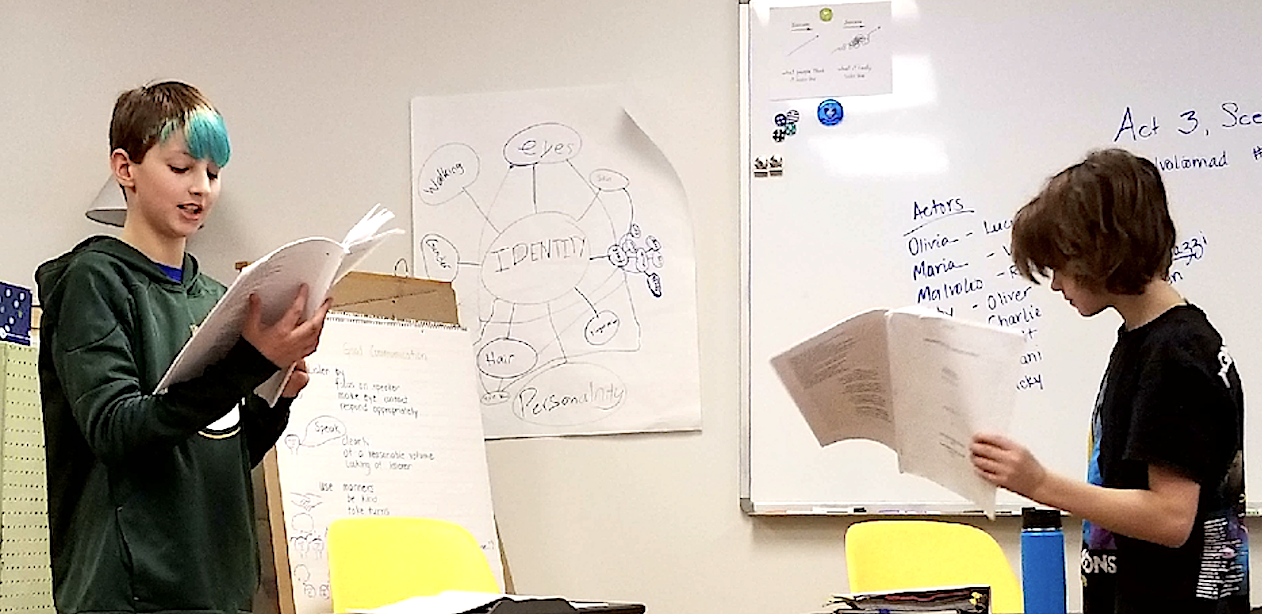

Imagine student bloggers, photographers, and commentators live reporting on a scene from Twelfth Night performed by their peers and expressing their opinion on the madness, or sanity, of Malvolio. Or a mother-may-I style game in which Viola in disguise as Cesario is courting the Duchess Olivia. Over the course of the scene, the class decides if the suitor moves forward, backward or stays in place based on the impact of the lines.

Our Shakespeare unit

Our 6th grade curriculum centers around the theme of Identity and Origin. Because of our small and close-knit community, I rotate through three plays, each exploring the theme of mistaken identity: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Twelfth Night, and As You Like It. At the center of each, however, is the unabridged Folger edition of the play in Elizabethan English.

On the second day of our Midsummer unit, we unpack the characters, mapping them by setting and associations, adding symbols to serve as clues of roles and relationships. These maps become a well-used resource as students gain familiarity with the characters. They also serve as a pre-set for discussions of forest vs city; magical vs. human; and wilderness vs. civilization that will follow.

Day three has students reading through a short scene from the play with only the context of the character map and that first batch of lines. Students stumble over pronunciation and meaning the way they might when tackling new vocabulary or syntax in a world language program. And then comes a spark of connection: “Nay, faith… that’s my line! The one I said when we tossed the ball around.”

The sense of mystery draws students in: a few lines, a cast of characters, a scene taken out of context. And they love it.

Michael LoMonico has captured this beautifully in his story That Shakespeare Kid (2013), a contemporary novel with a fairy tale feel that centers around a class studying Romeo and Juliet. Their teacher begins with a traditional approach, and then, challenged by her students, begins to follow the Folger method.

LoMonico, both an English teacher and Folger board member, knows the method well. His story is like a YouTube video on how to teach the plays, but with enough teen romance and snark that it resonates with students as well.

It’s true: Act One is hard, the language is new, the characters complex and many. But as students become comfortable with the text, I begin to hear snippets of lines echoing down the hallway. “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and others have greatness thrust upon them.” (Twelfth Night, 2.2.143)

We frequently end our day as a whole middle school – something we can accomplish with a student body of forty – a moment of reflection, a few announcements, a quick game.

Recently, I challenged students from previous years to dust off the passage they had memorized during their study of Shakespeare. Giggling, they delivered, starting with a choral recitation of the Seven Ages of Man speech memorized two years prior. “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players…” (As You Like It, 2.7.146…)

A new approach to Shakespeare

If you’re looking for a new way to teach Shakespeare to any age, grab both Shakespeare Set Free and That Shakespeare Kid. The well-thought-out lesson plans in Shakespeare Set Free and the illustration of the approach in LoMonico’s novel make an excellent pairing.

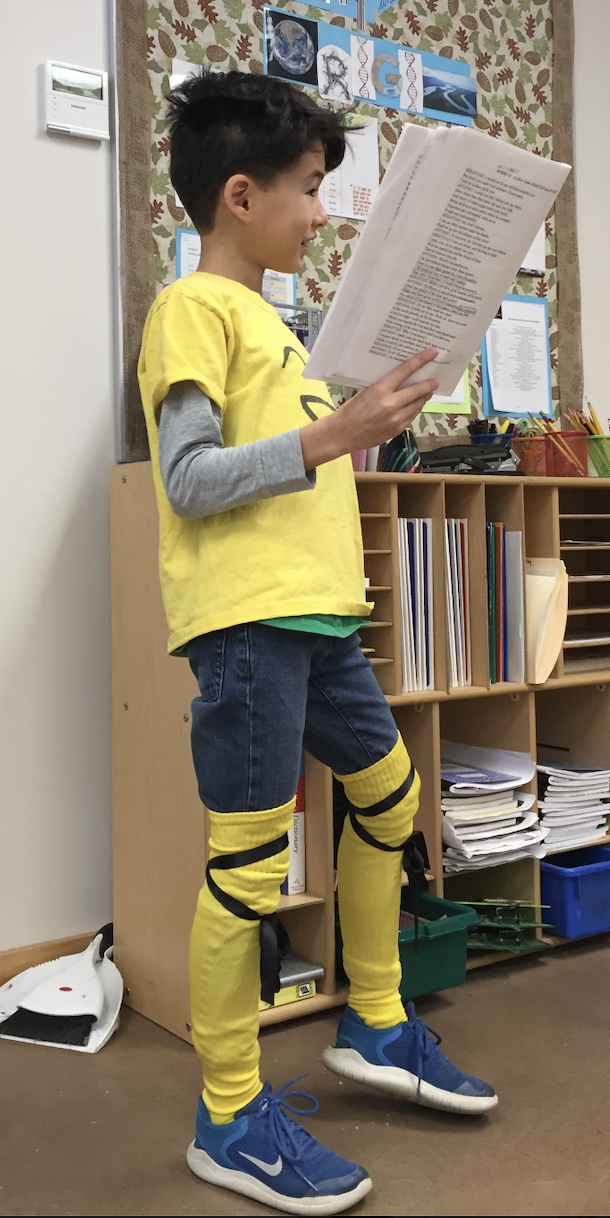

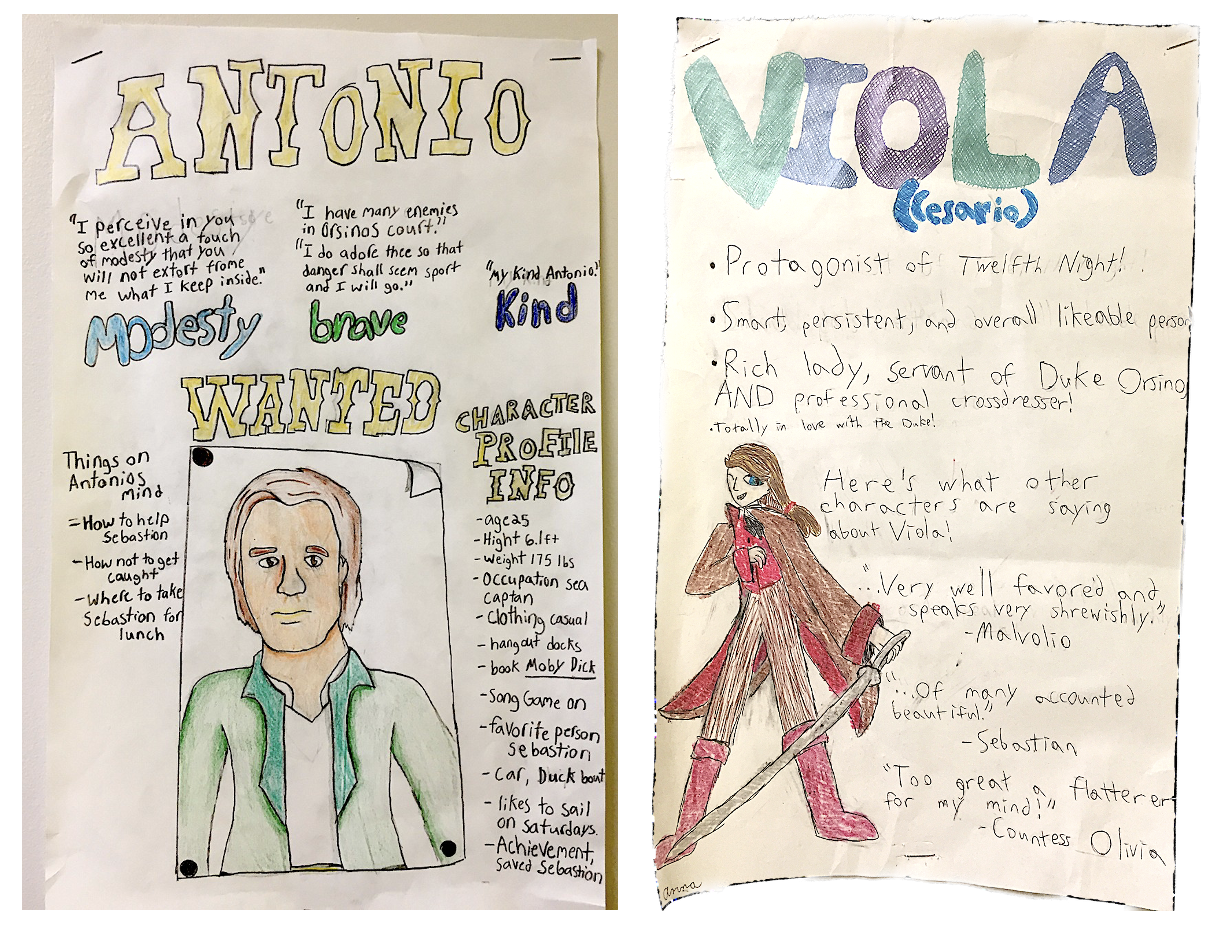

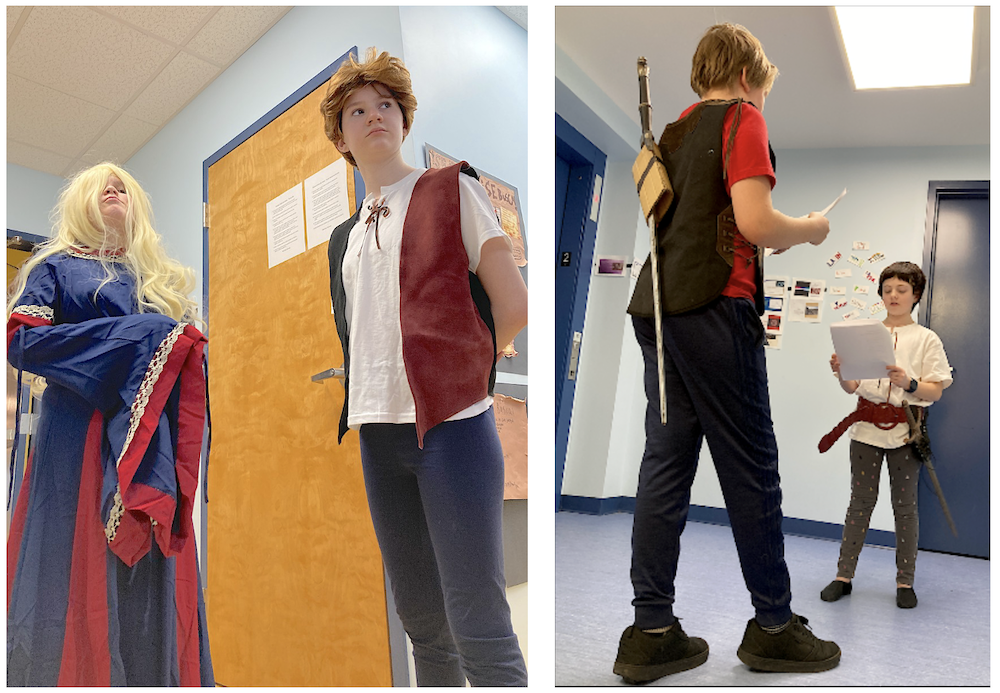

It’s festival day. Students have read the play in its entirety, explored a character in depth, written a paper on theme, and chosen a scene to workshop. They created costumes and props, added sound effects, chose a setting and time period, rehearsed, and many have memorized lines. Parents gather expectantly and the scenes begin.

Jeny Randall is the Middle School Director and language arts teacher at Saratoga Independent School in New York State. She also oversees the curriculum and program development for grades 6-8. Jeny is a Responsive Classroom certified teacher. Outside of school, Jeny teaches yoga, reads whatever students send her way, and spends time with her family, outside if possible.

References

O’Brien, Peggy. Shakespeare Set Free: Teaching A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, and Macbeth. Simon & Schuster. 1993

LoMonico, Michael. That Shakespeare Kid. CreateSpace. 2013

Folger Shakespeare Library. https://www.folger.edu/. 2024

“Love this! As a 6th grade teacher myself, I can totally relate to the challenges of teaching Shakespeare to young students. Your tips and strategies are so helpful – I’m definitely trying out the ‘Shakespeare in a Snack’ idea with my own students. Thanks for sharing!”