Add Imaginative Writing to Your ELA Classroom

Middle school teacher and instructional coach Ariel Sacks is the author of Who Gets to Write Fiction? Opening Doors to Imaginative Writing for All Students.

By Ariel Sacks

ELA programs and the standards that guide them give priority to expository and analytical writing. This is such a normal part of our culture, it probably doesn’t even seem strange. Imaginative writing is less practical and necessary for a successful life as an adult…right?

While the practicality argument may be true on some level, when it comes to young people’s development as readers, writers, thinkers, and members of diverse communities who will soon inherit the world from us, we miss out on a tremendous developmental force when we don’t seriously explore imaginative writing as part of our ELA programs.

The Art in English Language Arts

Literature is an art – it’s the art form at the center of the discipline of English Language Arts. What’s odd about the overarching emphasis on analytical writing in most ELA curricula is that we do not teach any other art form to young people in this way.

We don’t teach painting by primarily having students view, discuss, and write about paintings. We do not teach theater as simply an exercise in viewing and critiquing plays nor do we teach music or photography this way.

Both studying and creating art in a specific medium works well because the knowledge gained from the one action informs the other. When young people read about or view paintings, for example, creating in that same form is a natural response if we give them space and tools to try it.

Likewise, our productive language development is connected to our receptive language. How strange to read fiction regularly, but be expected to respond only in the form of an essay. Just like we know students need to conduct experiments to understand the scientific process, young people need opportunities to practice the art of literature to learn about the work of authors.

What We Can Do

The great news is that we can right this imbalance, and the results are amazing. With a few shifts, we can boost our students’ academic skills as well as their social emotional development and their sense of joy. We can lower students’ stress levels and help them take risks.

Here are my top five strategies for incorporating imaginative writing into the ELA classroom.

1. Tie imaginative writing to literature study.

Make it a regular way of engaging with literature, rather than a once-in-a-while activity or a stand-alone unit. (Breathe in story, breathe out story. Listen to story, speak story.) This is important, because it connects students’ reading and writing, and it gives them enough practice to develop skills in narrative fiction.

In my class, we read a lot of novels. For each novel we read, we engage in both creative and analytical writing. I create assignments that focus on a literary element that stands out in the text. For example, when reading books with a strongly developed setting, I have students try describing a setting of their choice in detail early on in the study. (Bonus: Tell students not to mention the name of the place they have chosen. Then, have them share with the class and have classmates guess what setting they chose to describe.)

2. Start with short exercises; build toward full stories later in the year.

Most students get overwhelmed by the assignment to write a fictional story right off the bat. (Most adults would too!) I often create shorter assignments based on the task of writing “a scene.” We can start by defining a scene – having students notice where a scene in a novel begins and ends. Then give students choices that play with elements of the book: add a character, change what happens in the scene when __________, rewrite a scene from a different character’s point of view, write the beginning of a sequel to this book.

I often start the year by offering a few choices. When we repeat the activity later, I have students co-create a menu of writing prompts with me. Their ideas can add a lot to the fun. The assignment allows students to make decisions with great impact, but without the pressure of creating a whole world with all the characters and the complete plot.

3. Teach just enough.

We don’t have to be giving a formal lesson to be teaching something. I try to teach as little as possible during imaginative writing – just enough to get students going, and then being generous with in-class writing time. The writing assignments teach a lot through experience, and I don’t want to overburden students with too many requirements.

That said, there are some very basic skills students will need in order to write fiction. Ideally, we just focus on one lesson per project. That’s why repetition of the activity is so important. They learn one new skill at a time, but practice the previous skills in each new assignment. Here are the three most urgent lessons I teach.

► Mini-lesson One: How Narrative Sounds. This is essentially, how to begin. Without this, some students will struggle to get started at all, while other students quickly jump into something that sounds like this: “Hello my name is _________ and I have…” and then they tell their idea in what sounds more like summary than story. In order to get started with narrative fiction, my classes simply look at how the author begins the book and the chapters within it. Students try borrowing an opening sentence, but adjust it for the purpose of their scene. I can model this or ask them to try first and then share out examples from previous student work.

► Mini-lesson Two: Paragraphing in Fiction. It’s telling that so many students draft stories with no paragraphing at all, as one endless block of text. Some students absorb the fiction form from the experience being readers, but most students need to be taught how to break up text into paragraphs. It turns out, this can be a very expressive aspect of the writing.

Have students look at an anonymous “block of text” story and then compare it to a page of nearly any contemporary novel written in prose. Then have students work together to investigate a familiar text to try to figure out when and why authors make a paragraph break. They will be surprised to note that in fiction there are often very short paragraphs, even just one sentence long! Have them practice on a sample text, and then apply to their own work.

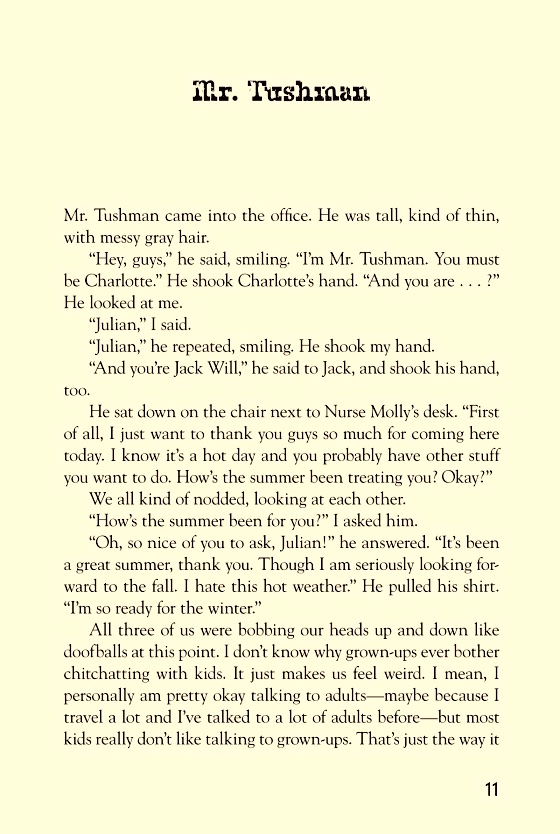

► Mini-lesson Three: Formatting Dialogue. Paragraphing leads naturally into this lesson, so sometimes we go over it lightly with paragraphing and then in more detail in the next assignment. Again, I have students observe a novel they’ve been reading, working together to try to deduce the rules. Then we share, clarify, and try it out together before students begin working on it in their own pieces.

This skill tends to need the most practice. For some students, all the pieces come together easily. For others, the starting place needs to simply be quotation marks and naming the speaker. Once they get it, they will be excited about how their writing now looks “like a real book.”

4. Honor the social emotional development students engage in when they tell stories.

Writing fiction is empowering for students. They get to make decisions of consequence – to be the authority about the world they are writing. They explore issues and feelings, and they can be vulnerable, without disclosing what parts of their writing might be based on personal experience and what is fantasy.

Keep in mind that growth is usually happening on multiple levels as students are writing imaginatively. For some students, identity growth will more important than academic growth in a given assignment. At the same time, the personal growth will strengthen the student’s connection with their writing and increase their academic confidence.

When we sense the writing is personal for students, our role is to be a supportive witness, but to give students space; let them lead the process. (On occasion, we may feel concerned for a student’s safety based on something they include in their stories. We can’t assume the writing is personal, but we also can’t assume it’s not. Make sure to follow your school or district’s policy in such a case.)

5. Create space for sharing and reflecting.

Through sharing their imaginative stories, students can learn from each other in two key ways. If we create a safe, inclusive space for sharing, students experience the same benefits that story generally has: it expands students’ worldviews and builds empathy across differences. When they share fiction as a class, they can understand one another in new ways.

Second, they can better understand how authors’ craft works. Suddenly, we have a group of very familiar, very three-dimensional examples of authors who have made interesting choices. I have students listen to each other and take notes: “What did the writer choose to do in this piece?” and “Which literary elements stand out to you here?” We discuss briefly, applying literary vocabulary to the choices and effects we notice in the student’s writing.

The purpose here is describing and appreciating the work, not so much offering constructive criticism. Later, students reflect in writing on their own choices: what went well, what was challenging and why, and what they want to work on next time. This helps them name their choices and successes, and assess their own progress on the technical skills. When students know there will be another chance, another time, they can assess themselves with less stress and anticipate their future growth.

One additional note about our literature choices: if we want our diverse students (and all classrooms are diverse) to engage in imaginative writing, it’s important to present a range of fiction authors and diverse mentor texts throughout the year. This sends a message that students’ identities are welcome and highly valued in the story world, and that will inspire confidence as they create content for imaginative stories of their own.

Ariel is the author of Whole Novels For the Whole Class: A Student Centered Approach (Jossey-Bass, 2014). More details on the strategies in this article can be found in her new book Who Gets to Write Fiction? Opening Doors to Imaginative Writing for All Students (WW Norton, 2024).