Complex Tasks Every Student Can Accomplish

By Karin Hess

Years ago I heard Dr. Howard Gardner make a comment that has stayed with me all these years: “Every complex task in life is a project, and we rarely – if ever – do them alone.”

Years ago I heard Dr. Howard Gardner make a comment that has stayed with me all these years: “Every complex task in life is a project, and we rarely – if ever – do them alone.”

I think the point he was making then, and one that has been supported by cognitive science since that time, is that we can tackle much more complex, performance-based tasks when we work on them with others – especially when we are first learning HOW to do those tasks.

When I was a middle school teacher, I learned that when my students worked on a challenging task together, engagement AND learning increased. When students collaborate, they develop both individual accountability within the group (everyone contributes something) and positive interdependence among group members (we support each other) while working towards a common goal.

The added benefit? Collaborating on complex tasks builds relationships, a positive classroom culture for learning, and a sense of real accomplishment for each individual student. When the team wins, everyone is a winner!

While approaches such as project-based learning (PBL) can require several weeks of instruction, there are alternative ways to deepen student thinking while working on complex tasks that do not require extensive time.

These tasks require students to transfer the knowledge and skills they’ve already learned (e.g., how to gather and organize information, how to use data displays) to produce real world (authentic) products.

7 Characteristics of High-Quality Performance Based Assessments

In Rigor by Design, Not Chance, I describe seven characteristics of high-quality performance based assessments (PBAs). These characteristics can be a guide to choosing, designing, and using any performance-based task.

1. PBAs Are Open-Ended

Prompts or situations allow for varied approaches, tools, and resources. While the contexts for PBAs are open-ended, the success criteria are consistently based in how authentic performances are evaluated for quality in the real world. For example, classroom video products employ similar criteria about quality that professional videographers would use.

Expectations for product quality are clear to students prior to getting started and guide their decision making throughout the process. For example, students might examine characteristics of graphic novels before creating one.

2. PBAs Offer Productive Challenge

Open-ended questions and tasks cause students to actively grapple with concepts, test different strategies/approaches, stretch their thinking, and explore alternative solutions and constraints when developing a final product.

Sometimes the challenge involves testing, getting feedback, and redesigning a solution based on feedback. Perseverance and learning from mistakes are honored.

3. PBAs Uncover Thinking

Products and performances require students to engage in substantive reasoning as they integrate multiple concepts and learn procedures. Generating questions, alternative approaches, or representations are integral to completion of the PBA task or developing a final product. For example, the creation of visuals such as diagrams and graphs uncover how the learner has made connections or interpreted findings.

4. PBAs Promote Authentic Doing and Sharing

Products and performances reflect real-world skills and dispositions for the context presented. Teachers need to consider how to help learners connect the skills and knowledge they’ve learned to create authentic products they can share with audiences beyond the classroom.

5. PBAs Integrate Knowledge and Skills with Student Decision-Making

When students collaborate to design and conduct a science investigation, for example, evidence of how effectively they transfer their science knowledge and skills and how effectively they worked together (collaboration skills) can both be documented.

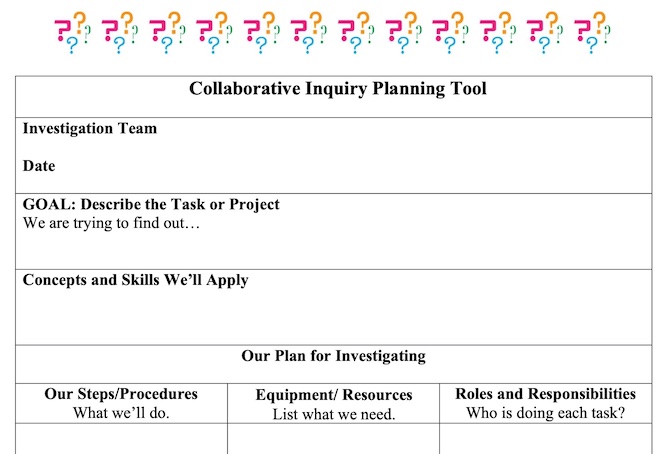

Students are given opportunities to make decisions about how or where they will work, materials they will use, questions they will investigate, or what their final sharing/product of learning will look like. My Collaborative Inquiry Planning tool is one way to guide students in co-planning their approach to an investigation.

6. PBAs Require (Far) Transfer

Products and performances embed opportunities to apply prior knowledge of multiple academic concepts and skills in novel, real-world contexts. Although academic skills and concepts are being assessed in terms of developing a final product, the processes used – how students decide which skills and concepts to apply and what they learn from trial and error and feedback – can also result in a learning stretch for most students.

7. PBAs Spark Reflective and Metacognitive Thinking

Unlike traditional tests that ask for recall of skills and concepts, performance assessments require students to reflect on and be informed by what they have done in the past; self-monitor what they are doing and how well it’s working right now; and articulate what was learned and how they have extended their own knowledge in the process (e.g., new insights gained, new connections made, new questions raised). Self-reflection is intentional in the task or project design, not an afterthought.

4 PBA Ideas That Are Complex and Accessible to Every Student

Here are four of my favorite PBAs for middle school students. Each task applies what they are already learning, can be completed by small collaborative groups, and does not require too much additional up-front planning for teachers. (Some planning tools and examples are included for teachers who might want to try these.)

1. Infographics

Throughout middle school students learn to gather and organize information. An infographic is a perfect way for them to display what they have learned and visually show how they organize and interpret that information. Infographics are engaging; they allow for creative ways to put information together.

If your students have never created an infographic, there are tutorial videos to introduce your class to what infographics are and others showing how to make infographics in Powerpoint or Google. Classroom stations can be set up for small groups of students to view and discuss what they’ve learned from tutorials about infographics before compiling information or designing the infographic.

Here are three easy approaches to using infographics:

• Explain a Process or Concept that students have already learned. The class might brainstorm possible topics and then form smaller groups to design different infographics as anchor charts.

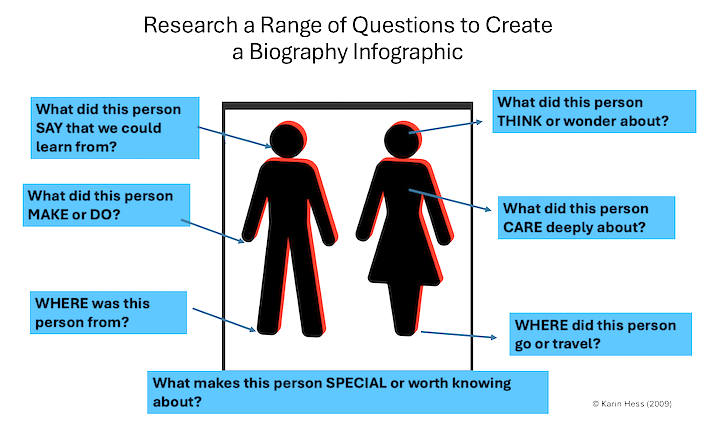

• Research a Person and create a biography infographic (above) using research questions that relate to a visual display: brain = what the person wondered about; heart = what the person cared about, etc. Biography infographics also work well for fictional characters or to personify science concepts (e.g., predator vs. prey). Visual displays will be much more engaging than written ones!

• Research a Current Issue relevant to students (e.g., cyber bullying, climate change) and use data displays to support key ideas uncovered through research.

2. Poetry Comics and Graphic Novels

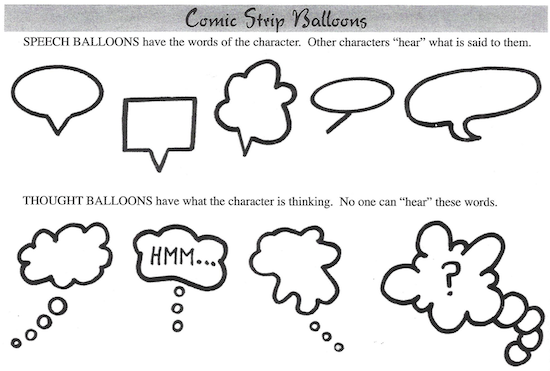

This is another visual way for students to present their understanding of something they’ve read. Using a template that creates panels for illustrations with speech and thought bubbles, students can breakdown a poem and illustrate it, or summarize a text they’ve read.

They can even create their own stories, such as placing themselves in a historical context and telling the story from their perspective. Comic strips and graphic “novels” do not have to be long, so they can be completed by a group of students in a fairly short amount of time.

3. Photo Essays

Photo essays are another visual way to tell an interesting story – real or fictional – or to illustrate a scientific process or procedure. Photo essays use a series of pictures with captions that tie the pictures together into a coherent whole. Students can take photographs, search for images online, draw their own illustrations, or even create scenes using tableaus.

A tableau is a static/frozen depiction of a scene usually presented by costumed actors on stage. Students can create their own tableaus by posing in costumes or with props to illustrate scenes of a story or event, taking a photo of each scene and assembling the photos into a display with captions. My 7th graders used to love staging tableaus to depict their favorite scene of a novel we were reading.

An important reminder in creating a photo essay: the pictures should provide the details and different information from the text. Just as in an advertisement, an actor might speak a few words, but the visual context that goes with the words makes it funny or interesting. Planning tools, similar to my 6-word memoir shooting script for a video, can help students decide how to use visuals to tell their story.

4. Text Decks

A text deck is a simple close reading strategy that breaks down a short text, such as a famous quote or poem, into meaningful phrases and then illustrates each phrase visually. A PowerPoint or Google slide deck can easily be used to create a text deck. Directions are simple:

(1) Students break down a short text into meaningful phrases. The lines of a poem might be used as written or broken into shorter pieces.

(2) Students copy each phrase onto a slide of the slide deck.

(3) Then, they identify the most important word in each phrase.

(4) Finally, they add an illustration for each important word to create a series of visuals that illustrate the meaning of the poem or the quote.

Students should be able to defend the choices they’ve made and the reasoning behind those choices. Here are two examples of text decks that illustrate what a final product might look like for an informational text or poem literary texts.

Final Thoughts about Complex Tasks

Not every assignment needs to be written as a summary, essay, or report. Visual representations of learning tap into multiple parts of the brain and therefore “stick” in the brain longer. PBAs do not have to require extensive teacher planning and resources in order to be doable in any classroom and accessible to all students.

Both the final products and the learning processes can be evaluated by teachers and by the students themselves using different types of scoring rubrics. Additionally, PBAs can be designed to elicit evidence of students’ ability to apply interpersonal skills (e.g., collaboration, leadership), intrapersonal skills (e.g., self-direction, self-reflection, goal setting), and academic knowledge relevant to developing an authentic final product.

I’m sure every veteran teacher in the state of Maryland perked up when they saw your article about performance-based tasks. Almost twenty-five years ago the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE) ended its Maryland School Performance Assessment Program (MSPAP) for students in grades three through eight. It tested all students in the areas of reading, writing, mathematics, science, and social studies over one week. There were extended constructed responses (ECR) as well as brief constructed responses (BCR). All of which were handwritten by students, unless their IEP stated a scribe. All students were submitting their whole writing process (not only final drafts, but also rough drafts, edits and revisions along with proof of peer conferencing) to be scored starting in grade three. The main objective was to change the instructional practices across the state of Maryland, and it sure did. I was a second grade teacher when the first MSPAP was administered in the late eighties. Later I left the classroom to become one of the school-based MSPAP instructional support teachers at a Title One elementary school. I saw value in this initiative and helped our school raise test scores to close the achievement gap. In the last few years of MSPAP I was a performance-task writer for MSDE, working on their mega-tasks that combined reading, writing, and mathematics for elementary levels. By 2001, the MSPAP ended. I truly believe that MSPAP was “way ahead” of its time. Maryland was on the cutting-edge expecting performance-based teaching and learning. MSPAP was a great undertaking and it served the state well. I for one believe it was a big success toward progressive teaching and learning in classrooms across the state in all 23 counties.

Thank you, Judith, for your insightful comments. I totally agree with and am saddened by what happened with the MSPAP. At about the same time in Vermont – when the NCLB tidal wave hit the country – many schools went from using rich, performance-based portfolio tasks to assessing tasks that were less complex and easier to grade. What we know now is that using performance-based tasks really did change instruction for the good of all students! Thankfully, many teachers like you saw the value in teaching students how to integrate and apply skills and concepts in authentic/ real-world tasks. This is one of the best ways to deepen student thinking. I hope you see some ideas in this article you can use. Keep up the good work!

Love the information about Infographics! Thanks!