5 Questions to Help Kids Become Critical Readers

By Marilyn Pryle

I knew some truths early on in my teaching career: That reading meant expanding, that it widened the mind and heart, that it nurtured compassion. I knew that writing was first and foremost about being present, about noticing.

I knew some truths early on in my teaching career: That reading meant expanding, that it widened the mind and heart, that it nurtured compassion. I knew that writing was first and foremost about being present, about noticing.

Once we are present, we can begin to express our authentic thoughts and feelings. Knowledge, empathy, authenticity, expression – these were the cornerstones of my convictions as a teacher.

For most of my career, I believed these cornerstones to be enough, and they were. I found that when I honored students’ intelligence, compassion, and sense of self, I saw them exhibit more intelligence, more compassion, and more self-awareness in June than when I’d met them the previous September.

Now they may need more

In the past few years, however, I have begun to wonder if students need more. I wonder if, in our pandemic-weary, conflict-ridden, anxiety-saturated world, students need new and different kinds of knowledge, tools for empathy, and practices of self-understanding.

Our current time in education feels especially overwhelming and exhausting. We became English teachers to support our students in reaching their fullest potential as humans. What does that mean now?

It’s no coincidence that the magical feeling of reading and writing – the feeling of being absorbed, transported, expanded, transformed – began to fade in classrooms proportionately as widespread, frequent, standardized testing seeped into schools.

The wonder of reading and writing, the curiosity and agency, died slowly as it was cobbled into skill-sized, testable bits and “right answers,” reduced to numbers that we perceive as progress or lack of it – and that children tether to their sense of self-worth.

Civil discussion has all but disappeared. There is only “right” and “wrong,” and we want someone to tell us the “right” answer, one that does not require too much discomfort or change.

We then can become entrenched with online friends, television channels, podcasts, preferred articles, and even live in communities that reflect ourselves back to ourselves. And it’s not even wholly our own fault: The algorithms are smarter than we are, and they’re just getting started.

What we can do

Here I outline five specific questions that help teach students how to look beyond a text itself – any text, in any form – and see the influences around it, the voices and sponsors, the craft and rhetoric, the intent and message.

A critical, experienced reader naturally questions these things. They are able to hold on to their own thinking and not be swayed by inflammatory rhetoric or savvy marketing. They are able to poke at a text like a curious scientist.

Critical readers also monitor how a text is landing within them. They recognize their own knee-jerk reactions, biases, and feelings, and they are able to choose how to respond in ways that help further solutions instead of exacerbate conflict.

The 5 Questions

In order to read texts critically, students (and all readers!) need to understand that texts – whether in print, video, audio, or online – are constructed things, made by someone (an individual, a team, or an organization) for an intended audience.

Too often, students take texts at face value, without applying the critical reading skills needed to navigate today’s media. The good news is that these skills can be taught and practiced, and that students can easily transfer these skills to every aspect of their media consumption, using five simple questions.

It is important to note that critical readers think of these questions in various, repeating, and overlapping orders as they read. They may jump from thought to thought, consciously or unconsciously, as they process a text.

Here the questions are numbered for the sake of reference, but in reality, threads of inquiry and understanding constantly weave themselves together throughout the entire experience of consuming a text.

1. What am I reading?

When a critical reader encounters a text, their first inclination is to figure out what it is and where it came from. On a basic level, this could mean identifying that a text is a poem instead of a short story, a news article instead of an autobiographical essay, or an instructional video instead of a blooper reel.

But deeper questions are embedded in this larger one: In today’s world, it can sometimes be difficult to realize that an online review or informational web page is really a cleverly disguised advertisement, or that a seemingly objective news article is really just persuasive propaganda.

Asking ourselves what we are reading, who wrote it, what the author’s background or culture values are, who the intended audience is, and who is ultimately funding the writing and the circulation of the piece – all these questions are crucial to critical reading and understanding.

2. What is it showing me?

This is the most often asked question by any reader, regardless of experience or skill level: What is the text saying? And of course, it is still a vital question here. But as with the first question, we should help students probe past the surface level. Readers should not only ask what the text is overtly saying, but what it is showing – what is between the lines – about human nature, society, and specific issues.

This might involve looking at questions around class, institutions, gender, race, and abilities; it might include separating pros from cons in an issue, or cause and effect. What a text is saying and showing is the information that a reader can glean from the words.

3. What is it hiding?

This question goes hand-in-hand with the last, and is one that readers sometimes miss. A text shows, but it also hides. Now more than ever, it is important to help students understand this. Perhaps the author holds biases they try to disguise; perhaps they are funded by a source that has an agenda. Maybe the logic pretends to be sound but actually is not. Maybe the cited sources are unreliable, or the ethical implications of the “shown” information are overlooked.

And sadly, in today’s world, and with children as a target, the algorithms are churning. Readers must ask themselves, What is this site suggesting I next read? What is it suggesting I buy? Whom is it suggesting I follow? Why? What is it perceiving about my thinking and tastes, and what does it want me to do next? If we can help students see even a little of this from an outside perspective, it will help them become more critical consumers of media in all forms.

4. How am I reacting?

Instead of addressing this question at the surface level, by simply asking students “What did you think?” or “Did you like it?” after they’ve read a text, we can nudge students to go deeper within their own thoughts and feelings, to name their emotions more precisely, and to think about their relationship to the text.

They might have a relevant and insightful connection, a pertinent question, or an informed, reflective opinion beyond “I liked it” or “I didn’t like it.” They might be in awe of the beauty or sophistication of the piece; they might be inspired to act. Helping students name and explore their reactions will not only nurture their critical reading skills but their critical consciousness as well – something that will benefit them far beyond English class.

5. How does it work?

English teachers excel at helping students answer this question, since traditionally our job has been to focus on the craft, technique, and inner workings of a piece of writing. We might direct students to examine the structure, tone, language, or sensory details in a text.

But when we help them look more closely, at the rhetoric, the emotional appeal, the attention-getting elements, and the accompanying visuals, we begin to help students go even deeper with the previous questions about showing and hiding. More specifically, we help students see the connection between writing skill and the writer’s ability to persuade, move, or manipulate the reader.

Thinking inside the framework

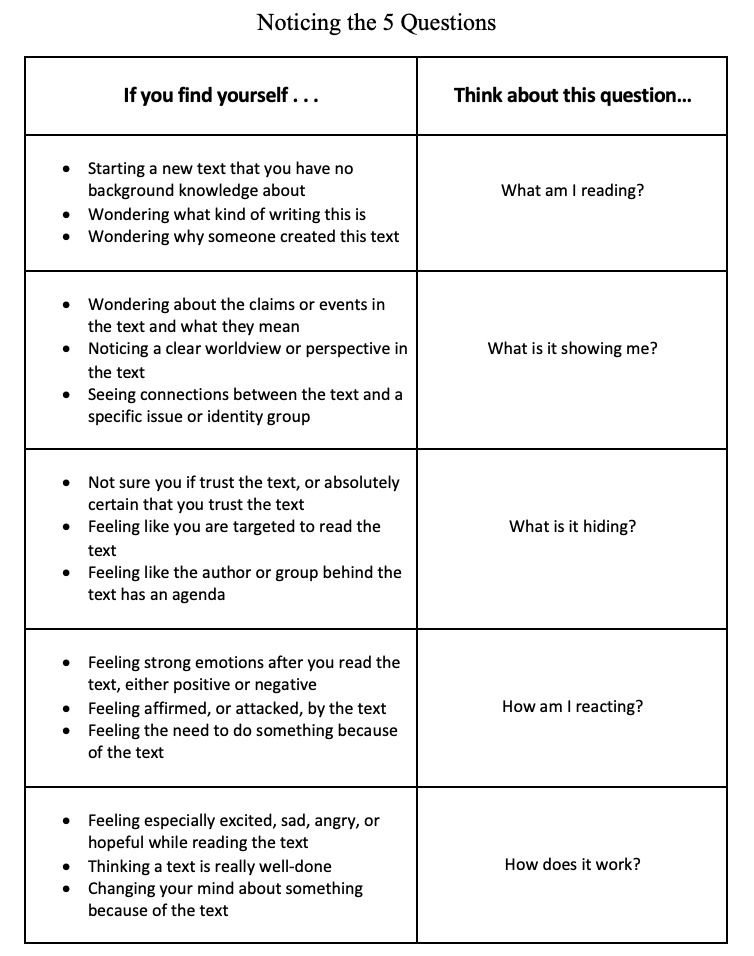

I have found that students enjoy thinking in the framework of the Five Questions. They appreciate these concrete doorways into a text, and the simplicity of the questions themselves. In the beginning of the year, I give them a chart (download here) to help them identify and clarify the questions as they encounter texts.

During the course of the year, I break down each question into smaller bits, helping students focus on just one small element at a time as they read: One day they might zoom in on the author’s bias, another the funding for an article; one day they might look at a text through the lens of eco-criticism, another through racial impact; one day they might examine the special effects used in a text, another a website’s algorithm.

One day, they could question if the producers of the text perceive them as part of the text’s audience or not. Another, they could wonder how to take action to respond to the issue raised in the text.

We always begin, though, with the 5 Questions themselves. If we can help students metacognitively identify how they are reacting to a text, we can help them process and respond with intelligence, reason, patience, compassion, or all of these at once. This is the work of teaching English now.

Find all the Five Questions articles here.

Look for her new Heinemann book, Critical Reading in the Age of Disinformation: 5 Questions for Any Text, coming in the Fall of 2024. Learn more about her work at https://marilynpryle.com/ and read her many articles for MiddleWeb here.

This article is adapted from material in Critical Reading in the Age of Disinformation. ©2024 Heinemann Publishers.