How to Differentiate the Teaching, Not the Task

By Mona Iehl

As a 5th grade teacher I often taught students who were still figuring out regrouping and place value, while I had other students solving 3-digit addition mentally. This range made differentiating to meet everyone’s needs difficult.

I tried many strategies: small groups, different colored worksheets with leveled tasks, and manipulatives for certain groups. These strategies took a lot of planning and were only effective sometimes.

Over the years my thinking about differentiating math word problems has changed quite a bit.

My differentiation then and now

I used to label students high, medium or low based on their assessments or standardized tests. Then, I would give my students different problems. I would offer small groups focused on teaching strategies at their level. This took a ton of planning and to be honest, I couldn’t sustain it consistently.

Now I think about differentiation as the level of support the teacher offers the students. I shifted my thinking from offering different tasks to supporting every student in reaching high, grade level expectations. This also was not easy, but this work felt much more aligned with my philosophy on education and equity.

As I made this shift, I made these four decisions.

1. I was not going to label students anymore.

Instead, I decided to see every child as having potential to participate and bring something valuable to the math conversation. That included Robert, who rarely participated in math class appropriately because he was often off task, flipping upside down in his chair, throwing pencils, and rarely doing what I said. And it included Jaylise, who was working on multiplying two digit numbers with concrete models. For a problem like 34 x 15, she drew 34 circles and put 15 dots in each.

I decided that even though these students and many more like them struggled in different ways, that didn’t mean they should be consigned to the “red group” and work exclusively on different standards or tasks.

Instead, I knew the strugglers had experiences and ideas they COULD use to solve problems if I supported them in the right ways. I believed that every student’s learning would be more meaningful if they began with what they knew and built their capacity and understanding little by little each day.

So, in my class, everyone would be in the same group and have the same label. And that label would be the “HIGH EXPECTATIONS FOR ALL” group.

2. I wanted EVERY child thinking in math class, every day.

I was no longer okay with some kids doing most of the participating and discussing.

This shift meant I needed a structure. I had to develop a way for my students to attempt word problems independently and also get support from our class community to understand the math. I knew I would need to make the classroom safe for every child to share their ideas, no matter what they were.

That is why every day we reviewed our co-created math norms and I held students accountable for following those norms through restorative reflections and conversations.

3. I had to stop being motivated FOR my students and instead cultivate motivation IN my students.

As teachers, we want our students to be successful so badly. We work incredibly hard to plan engaging lessons, build excitement and use strategies to get them to take ownership. Only to be met with sighs, frowns, and giving up quickly when things get tough. I can’t be the only one in that boat on a regular basis.

This is where I shifted my thinking big time. I decided to cultivate motivation in my students by doing hard things. You might be scratching your head thinking, “Say what?! But she said they gave up easily.” I decided to teach my students how to solve problems and struggle productively.

I know it’s hard to believe that students would be motivated to do difficult math. However, what I found from observing students over the past decade is that kids like doing hard things. They love puzzles. They love trying to climb to the top of the monkey bars. They like mysteries. If you want to get a child invested, present them with a mystery or secret you just can’t figure out. They will be pumped to help you figure it out. So, I decided to maximize this need for complexity and challenge and apply it to math class.

I cultivated a motivation in my students to solve word problems each day. I supported them as they learned how to struggle productively. We added tools to their toolboxes that allowed them to overcome moments of failure, course correct, and stay in a problem solving mindset. We did this through what I call a Word Problem Workshop, a student-centered daily routine where students productively struggle to problem solve and engage in a math discussion with their classmates.

4. I stopped making all the decisions for them. Instead I let them lead their own learning.

I wanted my students to have a voice and choice in their learning to help them build investment and ownership of their math understandings.

This meant I needed to consider when I was making the decisions (like telling students what strategy to use, where to sit, or who was to speak) and when I could let students start taking the lead. I opened up my classroom for more student choice, without letting things get out of control.

How did these decisions lead to differentiation using word problems?

Remember, differentiation doesn’t mean giving different things to students based on their level or label. Instead, it means giving different support and choice to students based on their current need.

That meant the first thing I needed to do was really know my students. Then I would be able to assess what they knew and could do independently and identify gaps where I could support them. Here are the steps I developed.

Step 1: Listen and observe. While students are working on word problems, the teacher must first understand what students are thinking and what they’ve tried, and get them to explain it before offering any support or suggestions. The goal is to ensure students have autonomy while also understanding what they are thinking. So, we watch them work and ask them to explain their thinking.

- Can you show me what you’re doing to solve?

- What are you doing in your head right now?

- Can you tell me what you’re thinking?

- How’s it going?

These questions allow me to get inside students’ brains. I tell my students, “I’m going to mine your brain.”

Listening is essential to this part of the process. When teachers listen closely, they are able to truly get an understanding of where the students’ understanding is before jumping to assumptions or providing assistance. Sit back for just a few seconds and truly listen to the students thinking. Consider your role during this step as to “get curious” about students’ thinking.

Step 2: Offer Choice. Before we get to the ways you might support students, it is important that when asking students to productively struggle with word problems you provide opportunities for the student to make choices.

We know word problems provide lots of challenges for students from reading, comprehension, and application of skills. However, setting up your classroom community and lesson routine can provide a predictable and safe structure while allowing students autonomy in their solving.

Start by allowing students the choice to solve problems in ways that make sense to them. This means strategies and models as well as math manipulatives that the student finds most effective.

Then you’ll be able to layer in other choices to build students’ ownership and investment in the math lesson.

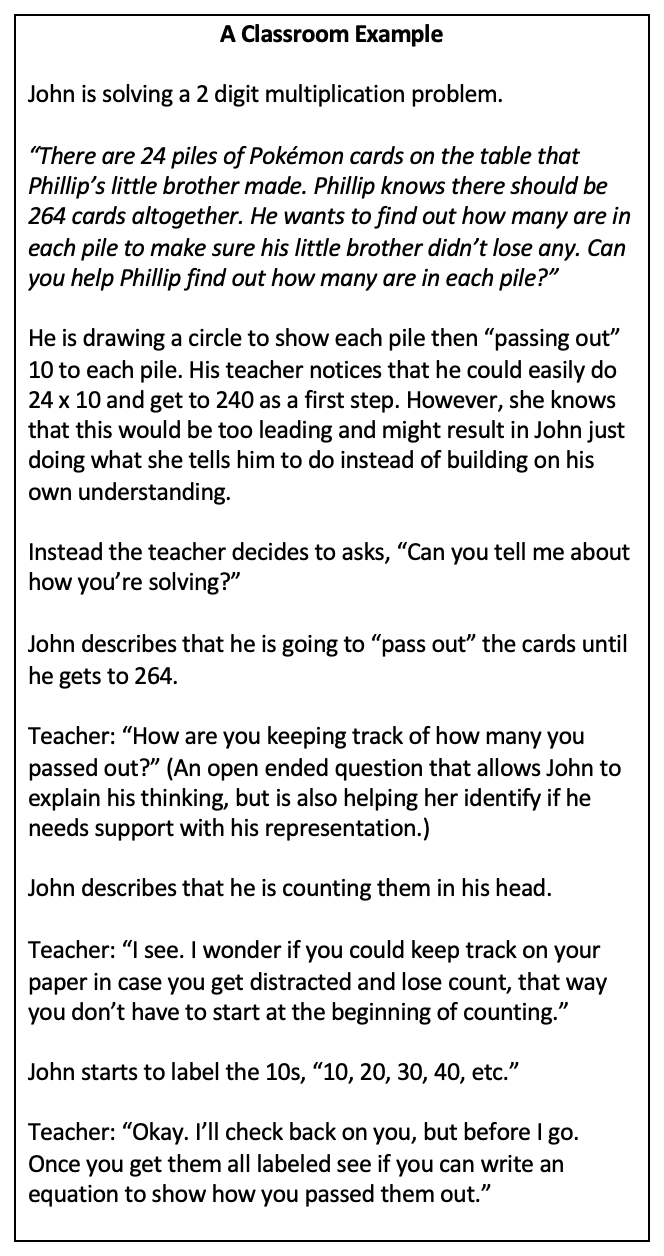

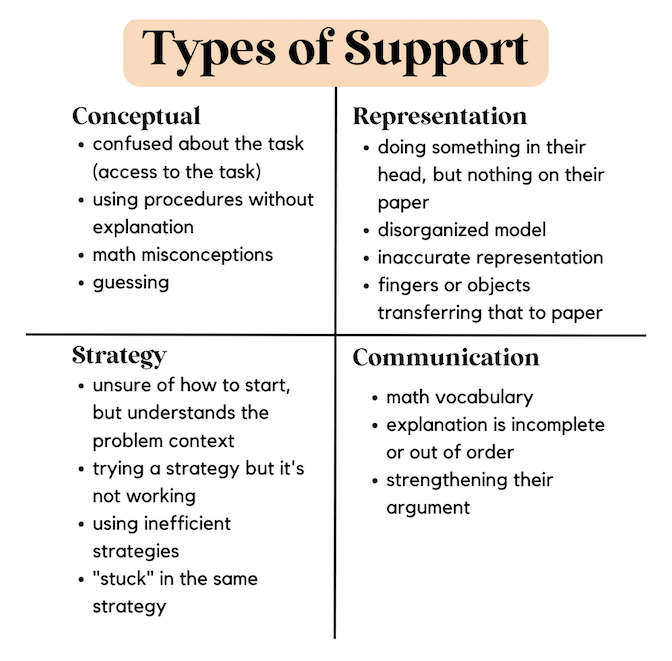

Step 3: Listen to Support. The types of support we give our students will differ depending on our “brain mining” – what the student shared. It can be overwhelming to “support” students on the spot, so think about the types of support we might offer to students. We might support students with their conceptual understanding, strategy, representation or communication. Some examples are included in the figure below.

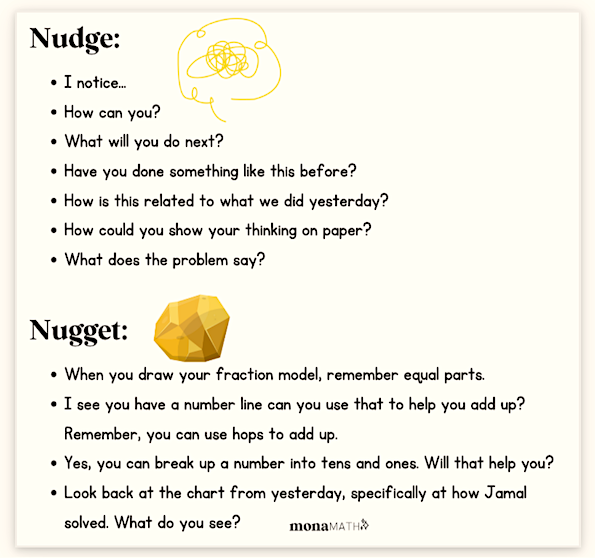

Step 4: Offer the Support. Once you have identified the type of support students might need, you’ll want to decide how you will support them. I urge you to consider giving them just a tiny bit of support that is easy to implement.

This bite size support aims to keep students engaged in solving problems in ways that make sense to them. Your advice or queries should enhance or question their methods without giving them something entirely new to do. I call this type of support a nudge or a nugget.

A Nudge is a question or prompt to re-engage students or direct their attention to a certain part of their math thinking. A Nugget is a piece of mathematical information (a vocabulary word explained, a concept or diagram).

The teacher knows that the labels might help John notice the multiplicative pattern and find a more efficient way to represent it. She is also taking note that this might be a worthy discussion point for the whole class.

This is the type of support that meets the learner where they are and honors thinking, while simultaneously nudging them to make progress.

The teacher knows that progression of learning happens gradually over time and is best done through experiences. That’s why she resisted the urge to jump in and show John how to solve more efficiently. She also knows that John will have the opportunity to engage with his classmates about different models and strategies to help him continue to make progress.

So we differentiate with support, while maintaing student choice

I hope you noticed the way John’s teacher allowed him to stay in the drivers’ seat of his solving, while supporting him and offering him a nudge. He got to decide whether or not he would adopt the nudge, but the option was there. And the teacher would be ready with further nudges and nuggets as John worked through the solving.

Building a student’s capacity to struggle productively through problem solving happens little by little over time. If we fall victim to the urge to “just show them” or “tell them what to do,” we lose out on the opportunity to let them make an investment in the learning process and gain ownership.

Seeing what brilliance and capacity exists in every child – and meeting them where they are with nudges and nuggets of support – allows us to empower students to see themselves as the mathematicians they are!

Listen to this episode of Mona’s Honest Math Chat podcast to learn about the research that undergirds her Word Problem Workshop.

Mona Iehl (@HelloMonaMath) has been a fifth- and sixth-grade math teacher in Chicago, Illinois for six years. She started her 14-year year teaching career at the primary level but found her home in the middle grades. This year she has taken on the role of coach. For more details about the teaching methods she highlights here, visit her website and browse her other MiddleWeb posts.

Mona recently took her passion for helping teachers and students find their inner mathematician to a podcast. Listen in at @HonestMathChat. More fluency resources for multiplication and division systems are available at her Mona Math TPT shop.

What is the data showing student improvement? Has it been replicated with the same success?

Mona Iehl points readers to a discussion of the research behind her teaching approach at the end of the article. Here’s the link: https://monamath.com/podcast/66-math-research-behind-word-problem-workshop/

Thank you for sharing your thoughts! I think that the infographics you include are incredibly helpful. As a special education teacher, I think providing those visuals and supports would be really appreciated by the general education teachers that I work with.

How do you ensure that you are getting accurate data about what each student can do independently?