Teach the Writer First and the Writing Second

By Matt Renwick

It starts with creating a space for students to describe a vision of themselves as writers.

It starts with creating a space for students to describe a vision of themselves as writers.

► What do they want to achieve as writers?

► What does that look like for them?

►What’s standing in their way of achieving it?

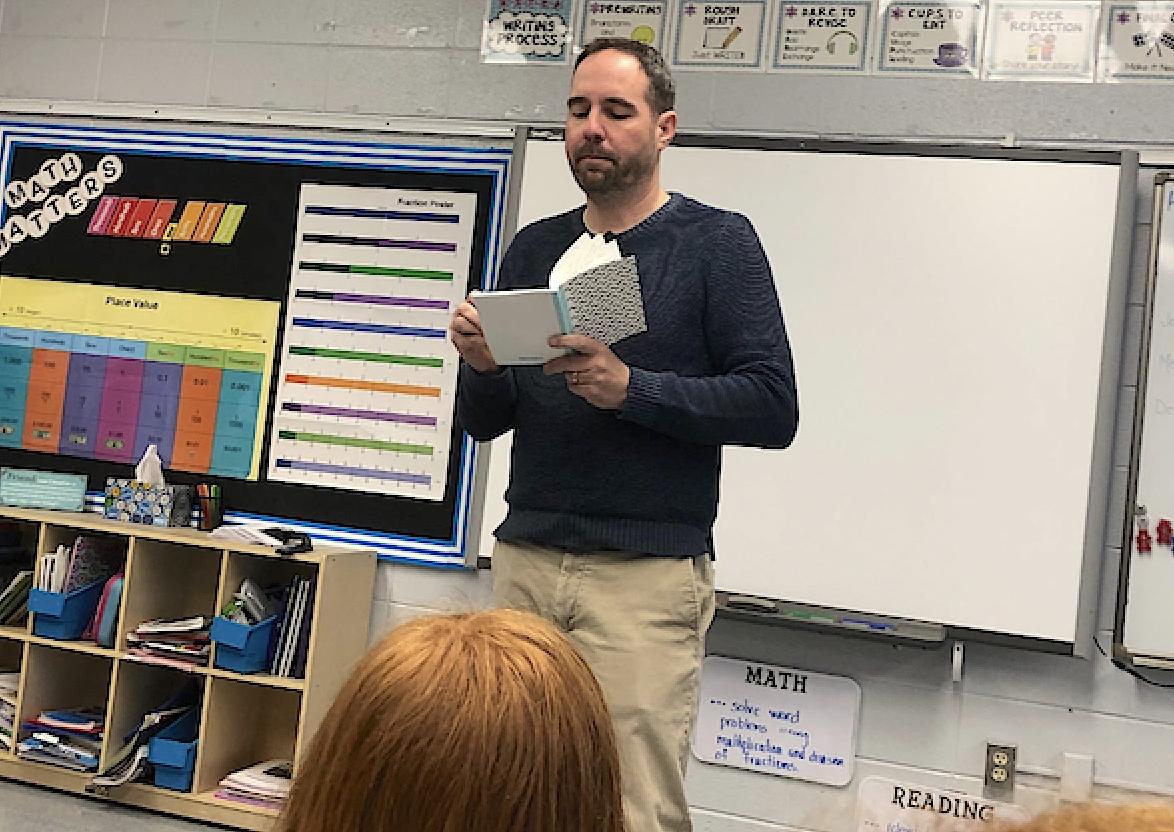

That’s what I set out to do when I demonstrated a writers workshop mini-lesson in 5th grade. Their teacher had already engaged the students in envisioning and goal setting. My job was to help uncover their obstacles as writers.

“Before we begin, tell me about your concerns regarding deadlines and writing.”

When I posed this question, the students looked at each other, smiling sheepishly, not sure how to respond.

“Really!” I affirmed. “I’m interested.” I held a small notebook and a pen in my hands, ready to take down their feedback.

Slowly, they revealed their anxieties about due dates and similar pressures related to writing.

► “I don’t like having to work on my stories at home.”

► “It’s hard to write when there are distractions.”

► “Sometimes we are talking and not focused on our work.”

► “My story is too long.”

I wrote down what each student said in my notebook. My note taking conveyed that I was listening. It also served as an assessment point. I could use this information during the workshop to guide my conferring. I could also come back to it at the end of our time together to see if we were successful.

I am not aware of any writing standard that describes how students should manage the challenges and the stressors of writing. The closest I can find is:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.6.5 – With some guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach.

What can we take away from this?

PROCESS SEEMS TO GET SHORT SHRIFT IN OUR CURRICULAR AND INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS.

Recognizing the gap between formal curriculum standards and the emotional and organizational hurdles of writing, I want to incorporate practical, student-centered strategies. These strategies not only acknowledge the challenges students are identifying but also equip our young writers with the tools they need to navigate and overcome them.

Next is a pathway from identifying the problem to actively seeking solutions that foster resilience and creativity in our students’ writing journey.

Begin with Student Concerns

As shared previously, part of my kickoff for a unit of study on writing was inviting students to share their concerns about deadlines and writing in general.

This approach helps identify specific challenges students are facing, such as working on stories at home, dealing with distractions, or managing long stories. It also gives a permission structure to admit the challenges of a writing life. Another possibility is documenting students’ concerns on an anchor chart instead of my notebook as a visible acknowledgement of their vulnerability.

Implement Writing Sprints

Break down large writing projects into smaller sprints. Help students create lists until they can accomplish a next action. This method encourages students to make progress in short bursts. They can focus on what’s important and feel less overwhelmed by the overall task of completing a coherent writing product.

Facilitate Peer Support for Strategy Application

After demonstrating a strategy, pair students up to help each other in applying the taught strategy. Peer tutoring strategies help ensure what was taught is applied accurately. It also distributes the power of a teacher’s instruction. We now have more time to monitor and coach.

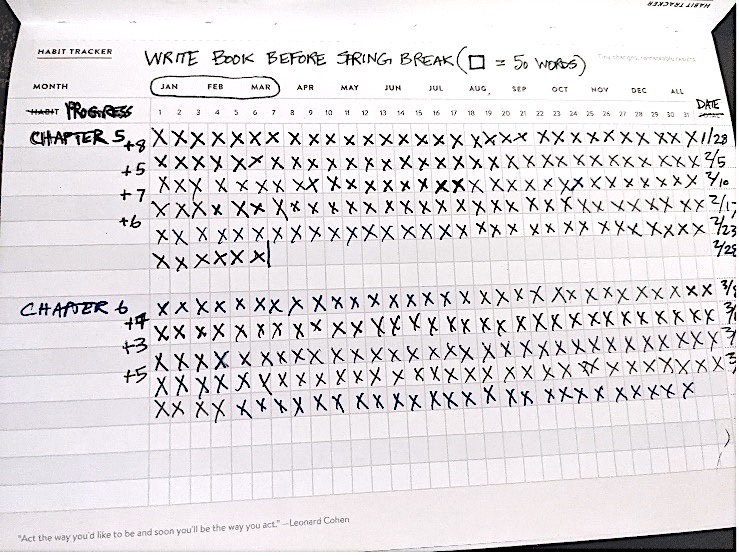

Use Journals to Teach Planning and Structured Reflection

Introduce dot/bullet journals for students to organize their writing projects and create character webs and use other graphic organizers. They can monitor their writing progress by creating word count trackers and documenting celebrations at the end of each writing session. For example, below is my word count tracker I kept while writing the first draft of my most recent book. Each X’ed block representing 50 words.

Sharing our own tools is a powerful way to model how writers operate.

In addition, students can be invited to use affirmations in their journals to build confidence and stay motivated. Possible affirmations students can write repeatedly include

► The more I write, the better I get as a writer.

► I have important ideas to share.

► People benefit from what I publish to the world.

Use ‘Public Conferences’ to Model Celebration and How to Give Feedback

It can be challenging to respond to students’ needs and deliver a mini-lesson all within one day. Public conferences, in which the teacher has a coaching conversation with a student about their writing in front of the class, gives the rest of the class access to the thinking processes involved in improving one’s work. This efficient approach ensures that all students can benefit from the reviewing experience and apply the strategies being taught.

Reflect as a Class on the Effectiveness of Strategies

At the lesson’s end, guide students to reflect on their initial work and assess how well the strategies led to improvement. This goes beyond a simple comparison of their initial and current writing drafts. Asking them to describe what they did and why they decided to use a certain strategy or guide can help identify approaches to add to their writing toolbox.

During my demonstration lesson, I had students share out publicly what they were noticing about their writing.

►“The tsunami ending I had was too short and weird, but today I was able to extend it. Now it makes sense.”

►“Comparing my last writing to today’s, I had better descriptions.”

►“I found a grammar checking tool to help me with my edits.”

Creating an open and safe classroom culture like this places value on experimentation and personal growth in writing. It encourages students to take risks and learn from each other, emphasizing the importance of each student’s unique process and contributions.

Next Steps

In their book Schools That Work: Where All Children Read and Write, Richard Allington and Patricia Cunningham have this to say: “Time matters, but how time is used matters more.”

No idea is guaranteed to work. It’s important to keep observing and asking questions about the impact of our practice. Was there a specific challenge for certain students? For example, did they not have enough time to write? Or did they not have the tools and strategies to manage their time effectively?

Considering this information, we have two general next steps:

1. Acknowledge our wins and best intentions today.

2. Prepare for better instruction tomorrow.

These next steps are not that different from the process writers engage in daily.

Matt is the author of Digital Portfolios in the Classroom: Showcasing and Assessing Student Work (ASCD, 2017) and Leading Like a C.O.A.C.H.: Five Strategies for Supporting Teaching and Learning (Corwin, 2022). Subscribe to his Read by Example substack and follow him on X-Twitter @ReadbyExample.