Teach Students to Read (and Write with) Video

By Jason D. DeHart

In this final post in my series on literacy, I have the chance to talk about a text that I love, and one which has been a major part of my reading life – the film.

In this final post in my series on literacy, I have the chance to talk about a text that I love, and one which has been a major part of my reading life – the film.

Linking popular characters across types of storytelling and parts of culture was a regular part of my life growing up. These representations of characters and stories included film, television, comics, novels, action figures, and more.

The Close Read/View

As noted in a previous post, scholar and author Renee Hobbs has written about the passive nature of film viewing as a classroom activity. She advocates for deeper student engagement with media. Scholars and authors like Frank Serafini have also written about the close and analytical work that can be done with film. In my dissertation study in 2018, one teacher told me about the power of hitting pause and noticing the features of film. The pause is so important, as is the conversation that follows.

Cinema does indeed have its own complex language. Standing back and watching the moving ensemble can be passive, but teachers can engage students in a critical process of not only reading but also creating their own videoed products.

Aspects of character and storytelling can be revealed in a split-second interaction or unpacked over a sweeping hour-long epic. These moments, frozen and explored in classroom conversation, can serve as mentor texts for reading, visualizing, and responding.

The Language of Literature Onscreen

Mise-en-scène. One of the first ideas that I often share with my students is that each moment and frame in a film is planned and arranged. What they see on the screen is a textual product of meticulous work, with each shot taking hours to plan and put in place, supported by location scouts who have scoured the world for the ideal spot, or digital artists who have been tasked with manifesting imaginative worlds that do not exist.

My classes watch the famous tracking shot from the movie Goodfellas and talk about how the scene comes to be, including the use of technology to follow a character. Then we talk about particular lines in the scene and what they demonstrate about the relationships among these characters (e.g., “What do you do again?” “I’m in construction.”).

The move from reader or viewer is always one to writer/maker/composer for me. As a young person reading comics, I immediately turned to making my own comics. Now that cameras and editing techniques are readily available on cell phones, the move to filmmaking is not as limited as it was once.

Students are often remarkably comfortable working through this process, and there is a support system for students who are less familiar from both the teacher and peer interaction in the classroom.

In fact, middle school students are most likely readily engaged in some kind of filmmaking at a high level, given the presence and popularity of brief video in today’s social media. Even if students are simply taking and arranging static images of themselves and their surroundings, this is a kind of filmmaking (the medium is, after all, composed of individual shots in rapid succession). In a recent TEDTalk activity to build arguments, my students stunned me with their use of humor and filters for imaginative effect.

From location to use of audio to framing, students can engage in multiple decisions in a short amount of time – even within a two to three-minute filmed response. This activity need not replace engagement with the written word. From reading, the next natural move is making.

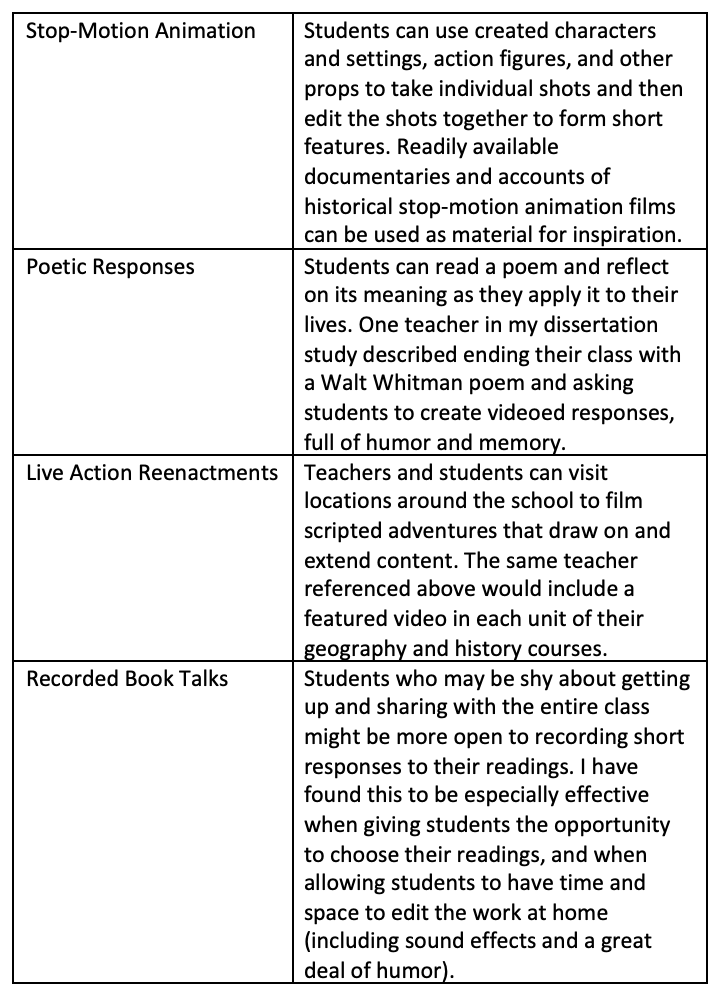

In short responses, when we are about to read a period novel, I ask students to think about the feeling of an age. Or about their major findings from their chosen readings. In the table below I list a few more ideas to consider when thinking about how to use short filmed responses in the classroom.

The Visual Age

With so many tools and technological advances, one might ask if life will ever return to a focus only on words and print as text. However, given the visual and artistic history of humanity, I wonder if this priority was ever an actual reality. I am reasonably convinced at this point in my life that popular culture and film had a significant impact on the reader and teacher I have become.

In this series, I have shared some ideas for creating and sharing, as well as for expanding what text means. May our conversation continue as I begin a new series of posts focused on how to support and challenge middle grades readers through critical thinking and text-focused work in literacy.

Dr. Jason D. DeHart teaches English at Wilkes Central High School in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. He taught English Language Arts to middle grades students in Cleveland, Tennessee for eight years, earned his doctorate, and served as an assistant professor of reading education at Appalachian State University before returning to his first love, the secondary classroom.

Jason’s work has appeared in Edutopia, SIGNAL Journal, English Journal, The Social Studies, and the NCTE Blog. See all of Jason’s MiddleWeb posts here – including a 3-part series with teacher and school librarian Jennifer Sniadecki on using picture books with middle level readers. His website Book Love: Dr. J. Reads offers book reviews and author interviews.

Write On! I’ve always believed in the power of watching, analyzing, discussing, and writing about a video in classrooms. I’ve used videos to provide background knowledge in classrooms at Title 1 schools forty years ago. Segmented viewing is a great strategy with a focus question at the beginning. Then pausing the video to discuss that segment will turn passive viewing into active learning. I’ve seen how the use of a video often provides the background knowledge necessary to level the playing field.