Nurturing Students As Collaborative Contributors

By Jackie A. Walsh, Emily Brokaw and Anna Salazar

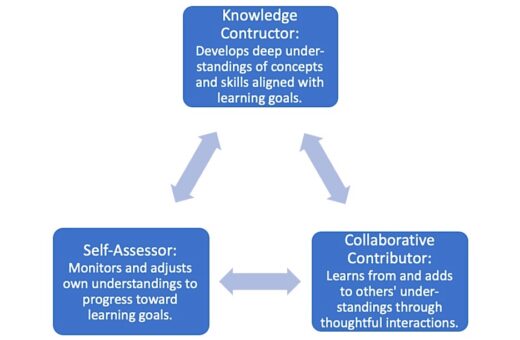

In our previous installment of Making Questions Count, we explored one of three important learner roles, Student As Self-Assessor. When students master this role, they advance their capacity as Knowledge Constructors.

In our previous installment of Making Questions Count, we explored one of three important learner roles, Student As Self-Assessor. When students master this role, they advance their capacity as Knowledge Constructors.

Yet they cannot realize their full potential as learners without engaging as Collaborative Contributors in their classroom community. Follow our conversation as we look more deeply into that role in this final entry of our series.

Jackie Walsh

Jackie Walsh: Learning is not an isolated process occurring solely in the learner’s mind. As researchers note (1), deep learning occurs in communities where students interact with one another and their teacher. The centrality to a skillful learner of being a Collaborative Contributor rests on this premise.

Three identified learners roles (2) are interdependent and mutually supportive:

Discrete skills underpin each learner role. Four seem particularly important to a Collaborative Contributor:

- active listening,

- voicing one’s own thinking,

- provision of feedback to others, which result in

- collaborative thinking and speaking.

Listening to understand others’ comments and perspectives is the gateway skill on which this role depends. This is a skill with which we all grapple, adults and school-age learners alike. Too often “listeners” are focusing on what they think and waiting for the speaker to stop talking so they can interject their own ideas. As teachers we can intentionally help our students develop this skill using a variety of strategies. Among these is the explicit teaching of how to use Think Time 2 while listening.

During structured academic conversations, teachers can use response chaining to reinforce listening as well as to strengthen voicing and support of peer feedback. This strategy involves the teacher

- asking a question, either closed or open-ended,

- naming a student to respond, and

- calling on another student to respond to the first answer by first restating the initial response and then indicating agreement or disagreement with elaboration.

Skills can be reinforced by providing students with tools offering explicit guidance as they develop skills associated with their learner roles. One such tool is the Student Q-Card. This can be reproduced, printing front to back, and cut to form a bookmark that students can easily access during classroom conversations. Additionally, students can benefit from anchor charts or other visuals that feature prompts and stems.

Anna Salazar

Anna Salazar: I have a vivid memory of my summer school classroom a few years ago, where I paused to give students time to reflect on the content we had covered, then provided them with question stems for use in creating clarifying or exploratory questions.

“This is a collaborative learning environment where we use your inquiries to drive our learning,” I explained. And it was a moment of epiphanies…one of my more hesitant students was quickly responding, “You mean, we also contribute to your lesson planning? I can ask questions?!”

The dynamic in that summer school class changed because students realized what their education could be, and it stuck with me throughout my teaching career.

Jackie: Anna, you strengthened your students’ will to invest by inviting them to take ownership of their lessons. Hattie and Donaghue (2016) argue that students not only need the skills to pursue deeper understanding of content, they also benefit from the will to invest in learning – the curiosity and willingness to explore what they do not already know (3). These are dispositional traits that support collaborative endeavors.

Anna: Students are innately curious, but it is only when they are invested that they are more willing to explore what they do not already know. As a U.S. History teacher, I am using student curiosity to drive the lessons. At the start of the school year, I introduced think-time to my students. And as many can guess, someone said “Does this mean I can’t just blurt out answers anymore?” As a class, we paused to review what they should do when a question was asked.

As the semester progressed, students would go through the steps of using think time and notice how much more engaged they were. Think-time created a more equitable opportunity for all students to understand the question, make connections, and have time to express their response. As we progressed through content, I also realized that – after hearing answers – more students would participate in the dialogue.

Often, some students would express they misunderstood the question and as a result that led them to a different answer. As students had more practice using think-time, students were more willing and even less afraid to ask questions that they were left with.

It was exciting for me to receive these questions as feedback, because I could see they were integrating their knowledge, self-assessing their understanding, and collaborating with their peers to ask questions.

Jackie: Another essential disposition for Collaborative Contributors is a sensitivity to equitable participation. Response structures and accompanying protocols, which establish how students are to engage in communicating their ideas or answers to questions, can scaffold student development of this and other dispositions while providing them opportunities to intentionally use core skills.

Emily Brokaw

Emily Brokaw: I agree. I’ll never forget a time in my classroom where I desired to have students engage in academically productive discussion and collaboration and tried to do so by instructing them to “just collaborate.” As you’re guessing, the ensuing reality was far from my desire.

Protocols give us and our learners the ability to ensure that every member of the classroom can contribute to the collective learning. The structure they provide ensures that we don’t only have our confident learners overpowering the discussion but that all students can contribute because they know how and when to do so. As Zaretta Hammond writes, “Protocols create ways into the discussion for students typically left out.” (4)

In my coaching role, in addition to encouraging teachers to incorporate protocols in upcoming lessons during planning, I continually engage them in experiencing the benefits of these structures during professional learning. Below are a few of my favorites. These and many other protocols are fully documented and downloadable in the open-access column at https://nsrfharmony.org/protocols/.

- Constructivist Dyad: This short protocol supports learners in practicing the skills of being an active listener and holding open space for others to fully share their thoughts. As mentioned in the Zarreta Hammond article cited above, it is also great to use for short social-emotional learning check-ins and discussions.

- Four A’s Text Protocol: If you are looking to build students’ understanding of and ability to make arguments, this is the protocol for you. Students gain practice with analyzing a text and synthesizing the arguments with their own insights.

- Text Rendering Protocol: This structure allows group members to build on each other’s understanding of the text or content with clear guidelines on what to share. It serves to lower the stakes of the discussion and support our more hesitant learners.

- Connections Protocol: This one has become a sacred ritual in my graduate school program! It is a useful response structure for controversial or pithy content or even can be modified and merged to be similar to a morning meeting. If you are looking to build your and your students’ comfort and skill with think time, the Connections protocol is a great tool to do so.

Anna: My emergent bilingual students enjoy the think-write-pair-share protocol as they begin to become more confident and comfortable with responding to questions. They are often hesitant to express their answers aloud in a whole-class setting. Having that time to think and write down their answer is sacred to them because they often have a lot of really good ideas to share.

As these students talk with their partners, they are able to get feedback on their answers from a peer who may make suggestions for improvement before they share out to the whole class. I notice that this leads to students asking all sorts of questions; for example, “Based on the article we read, I concluded …… Am I on the right track?”

Sometimes the partner reading a written response summarizes the response and asks clarifying questions. This creates a more dialogic classroom, one where students are collaborating and building on each other’s answers and reflections.

Jackie: Thrill is the third factor in Hattie and Donaghue’s conception of a successful learner. Thrill consists of “the emotions associated with successful learning.” Anna, I can only imagine the feelings your reticent bilingual learners experience as they successfully offer their ideas to the classroom learning community.

This affirms my belief that students are more likely to experience this thrill when they invest in learning with and from one another. And, according to Hattie and Donaghue, collaborative learning is most important when students are consolidating deep learning.

Emily: By developing students skills as self-assessors, knowledge constructors and collaborative contributors, we are empowering them to experience the thrill of learning. At my campus we have a period dedicated to extracurriculars, and it’s during this time that I see all the learning dispositions and skills that we work to cultivate in our academic classes come alive.

As I walk around the building I see our debate team engaging in peer feedback protocols to refine each student’s critical thinking and speaking skills, our chess students are teaching their peers new moves, and our community service and multicultural clubs are finding an unmet need in our community and coming up with creative ways to add value to our culture.

None of these experiences would be possible if we were not continually working as a school to create a learning environment centered on the foundation of formative feedback. Without this, students wouldn’t be equipped (skill) or feel confident (will) enough to pursue their purpose with passion (thrill).

Jackie: Emily, I’m wondering about the degree to which you find your students possess this triad of traits when they enter your secondary classrooms?

Emily: All students are capable of engaging in deep learning through collaboration when they enter any classroom. The question really is: Do all students feel comfortable and confident in knowing when and what to contribute?

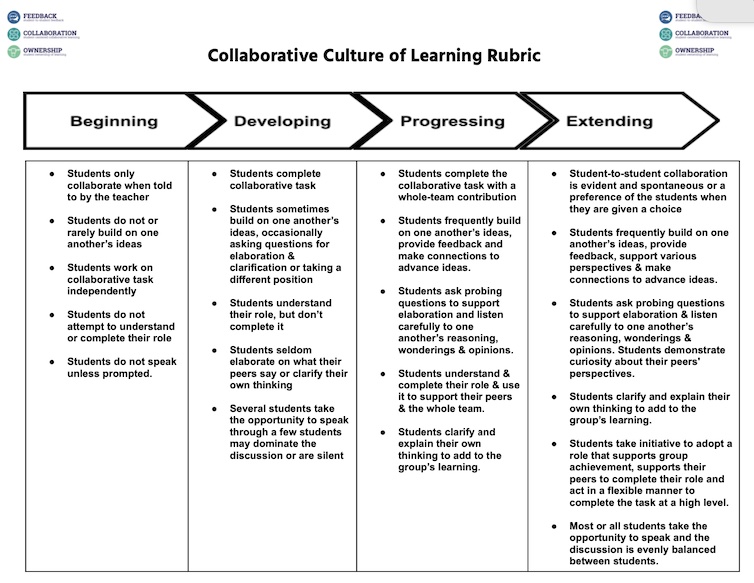

Clarity and opportunities (through protocols like the ones mentioned earlier) are the catalysts to maximize students’ impact as Collaborative Contributors. We’ve worked to support students’ successful collaboration by communicating clear expectations for what effective collaboration looks and sounds like.

The result is the Collaborative Culture of Learning Rubric provided below. By providing and instructing students on collaborative progressions, we find students know the expectations (skill), are confident in their abilities to collaborate (will) and can even see how their abilities as collaborative contributors grow over time (thrill).

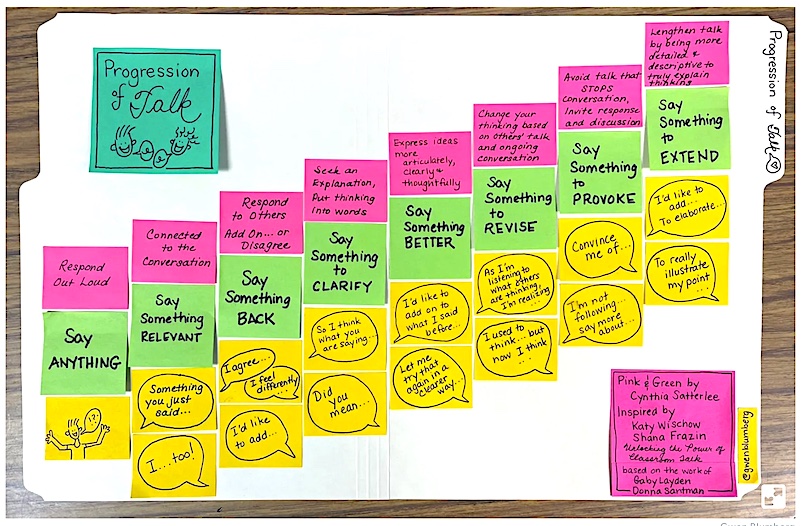

We also provide our students with anchor charts they can refer to as they participate in classroom dialogue. The example below comes from the Edutopia article Teaching Students How to Have an Academic Discussion (5), authored by Gwen Blumberg, a district literacy leader in greater Boston.

Jackie: We’ve had the privilege of sharing our thinking and experience with readers over the course of this school year, focusing on both teacher and student behaviors associated with quality questioning and formative feedback. When I began my deep dive into understanding the relationship between questioning and feedback, I was struck by a theme in the literature: If teachers effectively and consistently support students in the use of formative feedback, students will be able to self-regulate their learning.

This if-then statement reminded me of the late Richard Elmore’s admonition that educators need to become more mindful of the relationship between teacher actions and results for learners. Elmore inspired me to test cause-and-effect relationships in my own work.

Here are a few of these relationships implicit in our series for MIddleWeb.

- If teachers provide clear and explicit expectations for identified learner roles, students will experience greater success in learning.

- If teachers instruct students in the why, what, and how of Think Times 1 and 2, students will use these pauses to self-assess and correct or extend their thinking.

- If teachers strategically match response structures and accompanying protocols to questions, students will be more accountable and comfortable in sharing their thinking.

Emily: As I reflect on our journey with questioning as a tool for formative feedback I find myself cementing on the concept that these practices aren’t just part of the teaching and learning work, they are the work. If we as educators center students in the questioning, feedback and assessment process, we are cultivating agentic learners who have the skills to take on any challenges, pursue their passions and make positive changes in the world.

Anna: Students do not always come to us possessing the triad of traits we’ve explored in this series, but once they feel they are in a safe environment and they build the confidence, they begin to contribute more. Students want opportunities to be active collaborators on their learning journey. And as they get more practice and feel seen as contributors, they will start to recognize their identity as true learners.

We hope that you, our readers, are intentionally aware of the relationship between your instructional moves and your students’ learning. We encourage you to experiment with some of the ideas we’ve offered and look for the effects they have on your students’ learning. We’d love to hear from you!

See the entire Making Questions Count series here.

References

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, How People Learn II, 2018, p. 152.

- Walsh, J.A. (2022). Questioning for Formative Feedback. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Hattie, J.A.C., & Donaghue, G.M. (2016). Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model. NPJ Science of Learning, p. 16013.

- Hammond, Z. (2020). The power of protocols for equity. EL 77 (7). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Blumberg, G. (May 11, 2022). Teaching students how to have an academic discussion. Edutopia..

Jackie Acree Walsh, Ph.D. is an author and consultant focusing on quality questioning. Jackie is author or co-author of six books, two of which provide the basis for this blog series: Questioning for Formative Feedback: Meaningful Dialogue to Improve Learning (ASCD, 2022) and Empowering Students as Questioners: Skills, Strategies, and Structures to Realize the Potential of Every Learner (Corwin, 2021). Follow Jackie on X/Twitter @Question2Think. Find all of her earlier MiddleWeb articles here.

Emily F. Brokaw is a Campus Coordinator at Molina High School in the Dallas, Texas Independent School District where she leads her campus’s work with Assessment for Learning and helps to create the conditions for all students to become lifelong learners! Prior to this role, she was a social studies teacher for six years. Emily has a Masters in the Art of Teaching from Texas A&M University-Commerce and is currently pursuing a Masters in Urban Educational Leadership from SMU.

Anna K. Salazar is a U.S. History teacher at Molina High in Dallas ISD. She teaches in an Assessment for Learning classroom where she works to create experiences that empower students to be inquisitive and ask questions. Additionally, Anna supports new teachers to empower students to own their learning through intentional practices. She is in her fourth year in education and is a member of the Innovation in Teaching Fellowship.

So helpful! Thank you!