Try This UDL Higher Order Thinking Strategy

By Susanne Croasdaile and Samantha Layne

Samantha

Every educator views their world through a “lens” that colors their perceptions of what they see and how they will plan to address challenges.

Our lens is Universal Design for Learning (UDL) which is based in brain research and focuses on reducing cognitive load and developing students into expert learners.

Susanne

In our middle school, we use the UDL Guidelines 2.0 because we focus on something called the “Cautious Corner.” When we look at the lower-right side of the guidelines, we see a Cautious Corner of UDL Guidelines 6, 8, and 9. (This video explains it!)

Higher-order thinking skills and metacognition fall in this “cautious corner” of skills that won’t fully develop until students complete their neural development – around age 25!

That means students will need scaffolding and support for these skills for many years after our 7th grade class. We have to explicitly teach and scaffold the skills the entire time they are with us in the middle grades.

Current standards require complex higher-order thinking skills

People don’t learn complex higher-order thinking skills without explicit instruction. We just think they do.

When we see students engage in collaboration, communication, and critical thinking, it’s important to know that some person took the time to teach it, perhaps intentionally, and the student learned it and internalized it. For other students, it’s our responsibility to teach it.

With the executive function challenges our students face in middle schools, strategy instruction is the key to success.

Learner-owned strategies reduce cognitive load by chunking multiple steps into a single process and reducing the weight or “load” on working memory. To teach these academic behaviors, we have to model and practice them, using strategy instruction. In our school, we intentionally plan the First 20 Days of class to build critical habits and routines.

If all these things are in place, the student solidifies that routine in their long-term memory. They will use the higher-order thinking strategy as if on auto-pilot because their brain tells them “This is how we do it.”

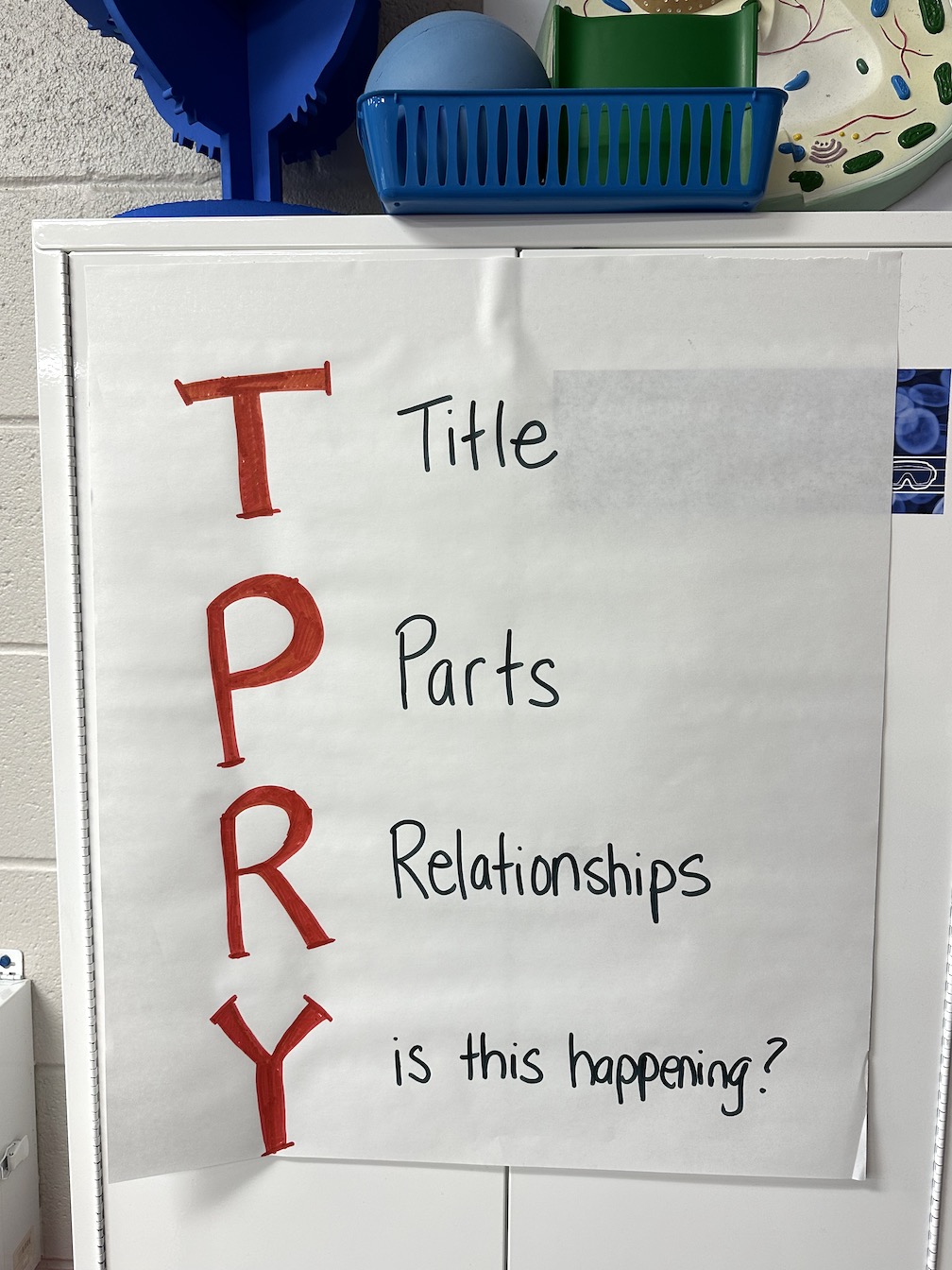

Using the TPRY strategy to “pry open” thinking

TPRY is a learner-owned mnemonic strategy based on science standards. It captures the NGSS practice of Developing and Using Models. Many of the complex higher-order thinking skills students need in middle grades today center on the crucial life skill of sense-making.

In science, history, math, and CTE, analyzing and creating models is a key sense-making skill. Here’s an example of the use of models in a physics class.

As a life science teacher and department chair, Samantha had experience with using scientific models with students and as part of professional learning. For those of us not as familiar with models, they are important sense-making tools that help students predict and explain the world. As diagrams, words, or equations, they are ways we record and communicate ideas about phenomena and systems (Schwarz, Passmore, & Reiser, 2017).

In the current science standards, teachers are expected to plan and implement experiences for students to create and use models of real-life scientific phenomena. In reality, many students spend more of their science classroom time on vocabulary activities and worksheets than models or model-building activities.

The taught curriculum has for years suffered from a mile-wide, inch-deep approach that leaves students with “disconnected ideas that cannot be used to solve problems and explain phenomena they encounter in their everyday world” (Krajcik & Merritt, 2012).

As a generalist, Susanne decided to learn more by enrolling in Edel Maeder and Kate Soriano’s excellent National Science Teachers Association 2022 webinar on Engaging Students in Developing and Using Models. The facilitators focused on three “all-purpose, back-pocket questions”:

- What do you absolutely need to include in the model (parts/components) to explain the phenomenon?

- What is the relationship or interaction between component X and component Y? How might you represent that?

- How or why are the components interacting (mechanism) in this way? How might you represent that?

These questions resonated with Susanne since they highlighted the critical features of developing and using models from the student’s perspective as well. If we distilled these questions into a self-talk mnemonic, might we make a higher-order thinking strategy that can be used in science…and history, math, and career and technical education?

After some discussion about the UDL Guidelines, the Cautious Corner, and learner-owned strategies, we drafted a mnemonic strategy. We shared it with skilled science and history educators across our region and landed on the TPRY Models Strategy.

We liked the mild humor in the strategy title (pronounced “tuh-pry”). After mapping Maeder and Soriano’s back pocket questions to “P-Parts” and “R-Relationships,” we distilled the rest into “Y-Why?” and a title (T) , with the idea that the title would serve as a summarizing check.

Using TPRY to analyze visuals

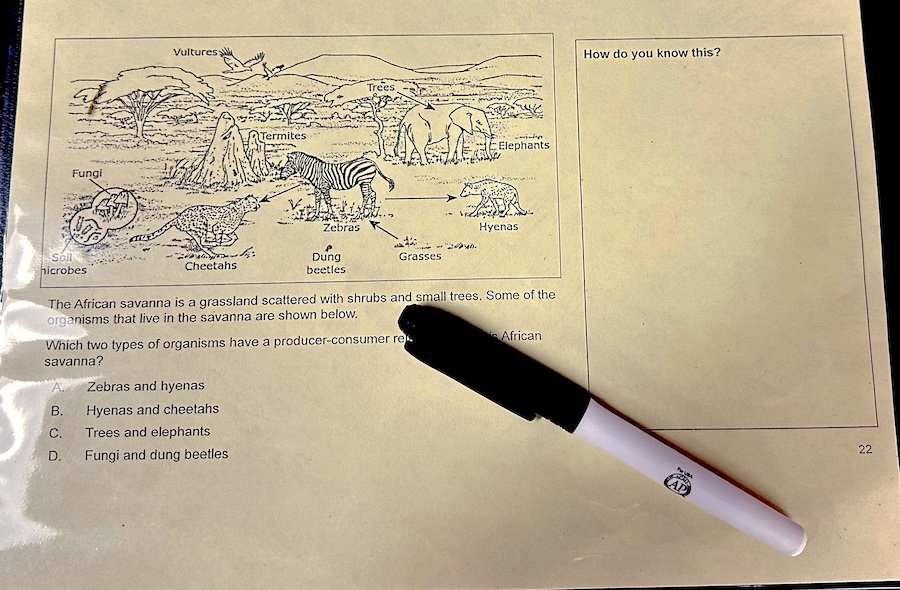

Samantha taught her 7th grade students to use the TPRY strategy to analyze visuals by using a food web. We were working towards learning how energy transferred through an ecosystem and had mastered a food chain, but we needed to understand how to read a food web diagram.

Students were given laminated copies of a food web along with dry erase markers (click to enlarge). Samantha led students through the parts of TPRY and they made notes on their copy. Students learned to use “T” to locate and read the title. If a title was not present, then students made a title to add to the diagram. Students made note of “P” for parts of the food web, which were the pictures, labels and arrows of the food web.

Students circled the “R” for relationships on the food web and discussed their notes with their neighbor. Students had to reflect on “Y” – why this is happening in an ecosystem. With guidance from the teacher, the students recognized that all living things need energy and that the diagram was showing the transfer of energy from producers and consumers.

It was easy for students to use TPRY to analyze visuals because we reviewed it each time we had a visual and it was posted in our classroom as an anchor chart. Students understood to “pry” something meant to open it, which meant they were “opening” a visual in order to understand the information it was relaying to us.

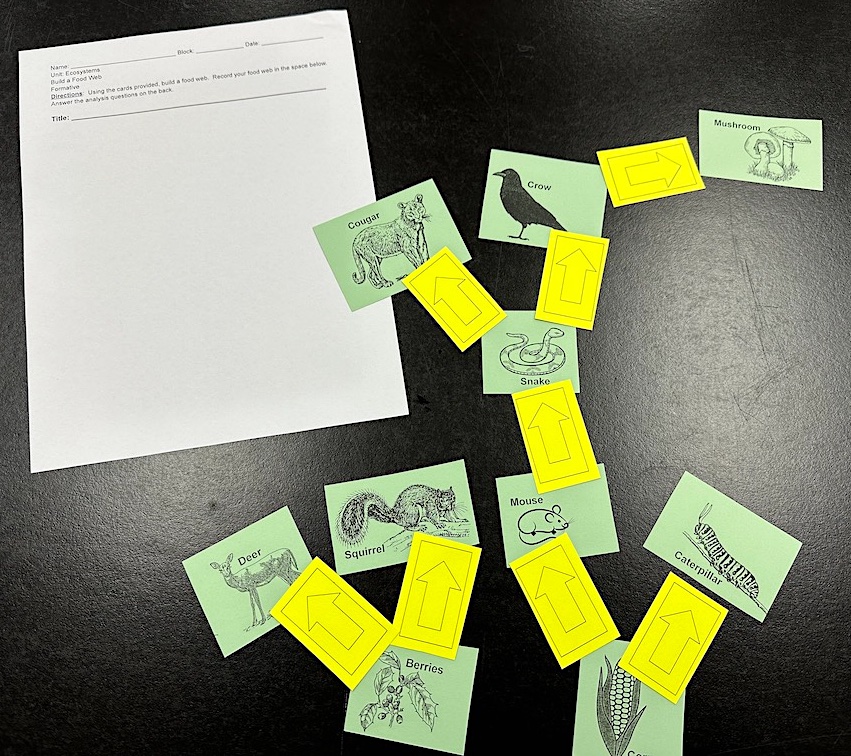

Using TPRY to build models

In addition to using TPRY to analyze visuals, Samantha uses it to help students build their own models. Students built their own food webs using pictures and arrows cut into cards, sort of like a card sort but sorting into a food web. Instead of students starting with a “T” for title, students started with “P” for parts.

Students recognized that the parts of the model were the animal cards and the arrows. After students sorted them into food chains and then connected them to form a food web, students used a worksheet to explain the “R” relationships between the plants and animals of their food web. Students explained to their neighbor “Y” these relationships existed in an ecosystem and finally gave their model a “T” title appropriate for the “P” parts (plants and animals) of their model.

This is our national launch of TPRY. Let us know what you think and if you’ll use it with your students!

References

Krajcik, J., & Merritt, J. (2012). Engaging students in scientific practices: What does constructing and revising models look like in the science classroom? Science Scope, 35(7), 6-8.

Maeder, E., & Soriano, K. (2022, January 27). Engaging students in developing and using models [Webinar]. NSTA. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQKdVE39zuA&t=1244s]

Schwarz, C., Passmore, C., & Reiser, B. (2017). Helping students make sense of the world using Next Generation Science and Engineering Practices. NSTA.

Check out ‘First 20 Days’ Planning Preps Kids for Success for more on how to plan strategy instruction in your classroom or grade level and use a calendar.

See all of Susanne Croasdaile’s

UDL articles here at MiddleWeb

Samantha Layne has been a middle and high school science teacher with extensive experience teaching English language learners and students with disabilities. She has served as a department chair and on the school leadership team. Samantha is a national professional developer for the University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning’s Strategic Instruction Model and currently leads a school-based peer coaching team. She also provides professional learning to teachers related to developing a school-based curriculum.