A Tool to Help Students Share Their Research

By Lisa Baldwin, Eric Chavez, Cassie Nettle and Sunday Cummins

Synthesizing information from multiple sources (a.k.a. doing research) can be tricky for middle grades students. Asking them to communicate what they learned from their research – orally, in writing or in the development of some sort of model – can feel even harder.

In a previous article we wrote about how inquiry charts are a simple way for students to organize their notes as they learn from each source in a set (Hoffman, 1992; Cummins, 2019).

Inquiry charts are also helpful when students begin to plan for what they will write or say or integrate into a project and then as they engage in this endeavor. As one of Cassie’s students put it, “I would look at the inquiry chart and it would give me advice on what to write.”

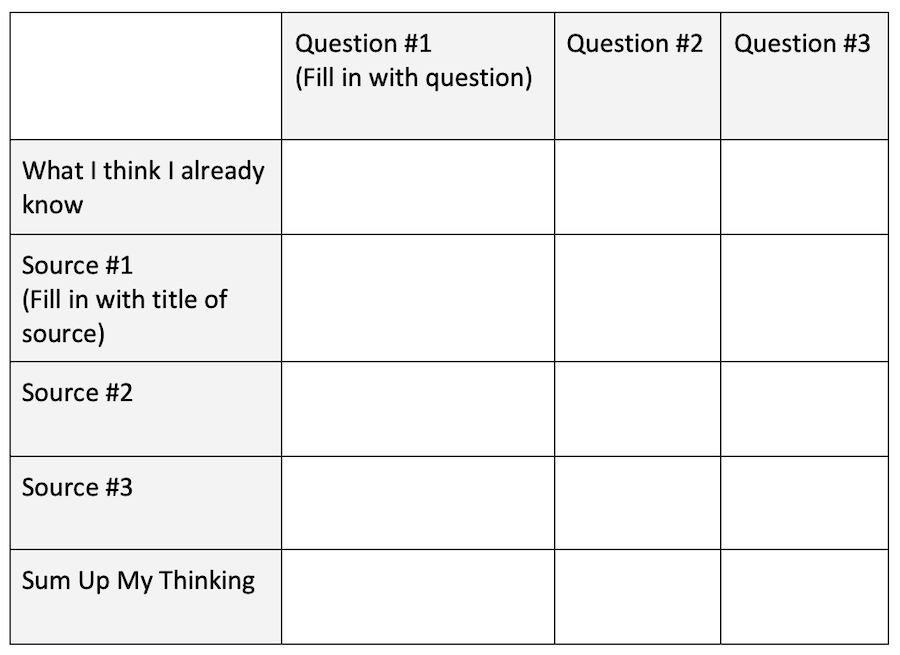

In the figure below, you can see a blank (minimized) inquiry chart. Students write clear, manageable questions for research across the top row and then list the resources they used down the left hand column. Then they take notes in the blanks.

The students get excited about filling in the chart because they begin to notice how the information in sources (e.g., graphics, video, short articles) is connected. As their knowledge of a topic deepens, they begin to see themselves as knowledgeable.

Minimized Inquiry Chart

Then comes the harder part – communicating what they have learned without simply looking down a column and regurgitating what they learned from each source. Supporting students as they move from research to communicating in meaningful ways may feel daunting at times. We have three tips to offer:

- Nurture talking with intention about their learning throughout the research process.

- Support students in using their inquiry charts to create a plan for writing or communicating in response to an engaging task with a clear prompt.

- Orally rehearse before and as they draft.

Let’s consider each tip in more detail.

Nurture talking with intention

Don’t wait until students are done with research to practice talking about what they have learned from multiple sources. As they complete the inquiry chart, students need to talk about what they learned from the source and how it compares to information in other sources.

This way the language they need to use when it is time to write or talk about what they learned is not unfamiliar territory. More importantly, we have found that it is not enough to just discuss; we have to coach students in how to use language to express their thinking.

This coaching starts with the kinds of questions we ask along the way. When students are moving from that first source to reading, listening or viewing additional sources, we include questions for discussion like:

- How does the author of this second text add to what you learned in the first text?

- What are the similarities or differences in the authors’ key ideas on this topic?

When they move into writing or planning for communication, we ask questions like:

- How will you combine those ideas?

- How will you reveal the contrast between these ideas?

As needed, we also provide sentence stems to support students’ language development such as:

- These two sources are similar/different in that…

- In the first source I learned that…but in this second source I learned that…

- The second source added on to what I learned in the first source, which is that…

- In all three sources, I learned that…

- I might combine these ideas by saying that…

Provide space for students to annotate and plan

After completing the intense thinking that needs to occur to fill in this chart, we have asked students to share what they have learned in various formats including writing a piece of historical fiction, preparing to present to students in the lower grades, and even just writing an essay about what they learned that was engrossing.

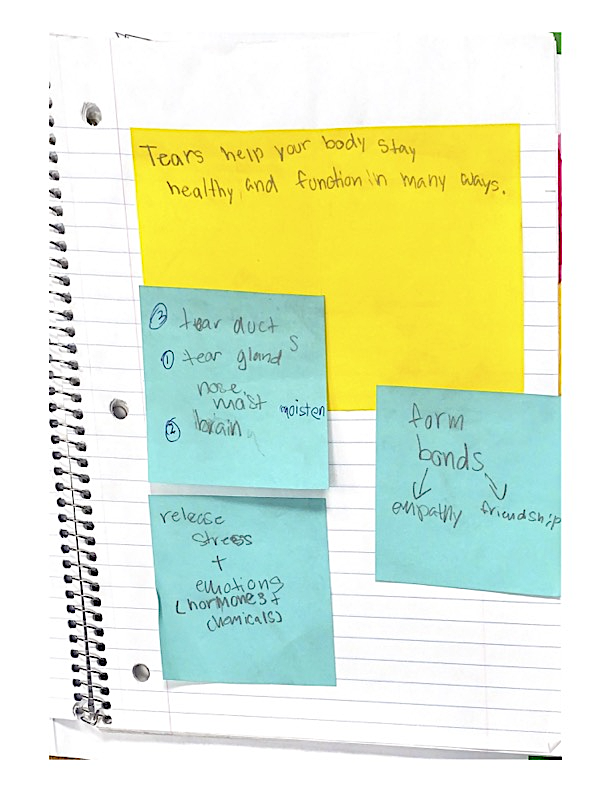

Cassie’s students wrote presentations on the fascinating topic of how our eyes’ tears impact the body so they could present to 2nd grade students and then lead a question and answer period.

Lisa’s students wrote a fictional piece about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried the city of Pompeii, integrating facts they’d learned. An engaging task (with a clearly written prompt) not only motivates students but clarifies which details in the inquiry chart will be helpful.

Depending on the task chosen for communicating their learning, students will probably need to sort the details on the inquiry chart in some way and then create a plan for what they will write, say or develop. Sorting details may involve one of the following:

- returning to the inquiry chart with colored pencils and circling important details that belong together

- simply drawing arrows between details on the chart that belong together

- marking with an asterisk important details to include.

Prompts we use to support our students include

- Looking across your chart, which details will support the idea that you want to communicate?

- How can you combine details from those two sources to help you say what you want to say?

Creating a plan for writing may involve constructing a skeletal outline or jotting key ideas on sticky notes and putting them in some order. We avoid asking students to rewrite copious amounts of details from the chart – that seems redundant. The key ideas in a minimal “plan for writing” serve as triggers for remembering what was learned or which details they need to consult in the inquiry chart.

Annotating the inquiry chart and planning for writing frequently happen simultaneously. As a student thinks through what they want to communicate, they may move back and forth from one process to another. Provide scaffolds as needed along the way.

Cassie noticed that even though the students had engaged in synthesis as they read all three sources, they needed support developing a main idea statement. She engaged them in a shared development of a main idea statement, encouraging them to think back to previous conversations and to look once again across the notes in their inquiry charts.

Once they had a statement, they practiced orally rehearsing it before writing it on a sticky note. Then they returned to the inquiry chart for key details to include in their plan (on additional sticky notes). The image below is an example of one student’s plan.

Orally rehearse before and as they draft

As students draft their pieces, provide opportunities for them to say aloud the sentences they are contemplating. This is different than just talking about what they are going to write or present. Prompt them to actually orally rehearse what they will write. You might say the following as support:

- How would you say that?

- Let’s look back at the details you want to include. How can you combine those details in a sentence? Try saying it aloud.

- I see that you have written about ______ so far. What will you write about next? Let’s practice saying that idea aloud in a sentence.

- Can I give it a try?

- What if we started by saying___? How could you finish that?

As the last two prompts reveal, this is also an excellent opportunity to support language development. You might offer a prompt like this to an English Language Learner, or you might be offering it to a student who needs to use more complex sentences in their communication.

The power of i-charts

The benefits of this kind of practice are immense for each student but also for their peers. We have found that they listen to each other rehearse and are able to build off their ideas. Sometimes students who are “stuck” get ideas they can contemplate as they think about what to write next.

We have seen a profound increase in our students’ excitement and engagement in research. The inquiry charts have been essential in supporting our students throughout the research process. This includes the critical thinking used in communicating what they have learned.

We have also found that students are applying what they have learned with the inquiry charts in all subject areas and are making strong detailed connections. We are planning on incorporating the i-charts into our units of study this year.

References

Cummins, S. (2019). Nurturing Informed Thinking: Reading, Talking and Writing Across Content-Area Sources. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hoffman, J. V. (1992). “Critical Reading/Thinking Across the Curriculum: Using I-Charts to Support Learning.” Language Arts 69 (2): 121-127.

Here’s a link to both articles in this I-Charts series.

Lisa Baldwin is a 4th grade teacher at Topping Elementary, North Kansas City Schools. She is a graduate of Avila University and holds a master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction. In 2017 she achieved National Board Certification in Generalist/Middle Childhood.

Eric Chavez is a 4th grade teacher at Topping Elementary School, North Kansas City Schools. He is a graduate of California State University of Long Beach and University of Missouri Kansas City. He holds a master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction Design.

Cassie Nettle is a 4th grade teacher at Topping Elementary, North Kansas City Schools. She is a graduate of Northwest Missouri State University with certification in Elementary Education and Middle School Mathematics. She holds a master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction from Peru State College.

Sunday Cummins, Ph.D., is a literacy consultant and author and has been a teacher and literacy coach in public schools. Her work focuses on supporting teachers, schools and districts as they plan and implement assessment driven instruction with complex informational sources including traditional texts, video and infographics. She is the author of several professional books, including Close Reading of Informational Sources (Guilford, 2019). Visit her website.