Help Readers Discover What a Text Is Hiding

This is Marilyn’s third in a series of articles about the 5 Questions teachers can use to help students become more critical readers with any text in any format. The complete series includes these articles: Introduction: 5 Questions to Help Kids Become Critical Readers | Question #1: What Am I Reading? | Question #2: What Is the Text Showing? | Question #3: What Is the Text Hiding? | Question #4: How Am I Reacting? | Question #5: How Does It Work? To see summaries of the complete series in one place, go here.

By Marilyn Pryle

I argued that if students are to have more confidence, agency, and critical skill when encountering a text, they must cultivate the mindset of examining all that a text reveals about itself rather than simply what it “says” on a surface level.

For Question #3, I want to go a bit deeper, past what a text might divulge about itself to what it is deliberately suppressing.

Question 3: What Is the Text Hiding?

This question is a natural response to Question #2. A text shows, but it also hides. This question teaches students to look below the surface of a text, below what is clearly or inadvertently revealed, to the parts that are intentionally quashed.

This can have a range of meanings. Perhaps there is an inconvenient fact or statistic that is pushed to the side, while another is inflated, or an author has a clear bias that is downplayed in the word choice, but evident in the tone. Perhaps the logic is shaky, or the text is rife with faulty logic.

Maybe the sources the author cites are unreliable, or even fake. Maybe the text is funded by a group or company, and this colors the entire message of the piece. Or perhaps the text itself is sound, but the suggestions for further reading or viewing are suspect, intending to lead the reader into a rabbit hole of a certain way of thinking or to a path of purchasing.

This question touches upon darker motives than the previous two questions. The first two questions – What am I reading? and What is it showing? – ask students to peek under the surface of a text, to investigate beyond the finished product, in an attempt to see the fuller picture of a text’s background and influences. This third question, however, prompts students to ask themselves if the text is deliberately trying to deceive the reader in some way, big or small.

Obviously, this is important. If students are to successfully navigate the myriad of content they encounter outside of school, they must be able to see beyond what is revealed. What is hidden in a text points to an author’s or creator’s purpose as well: We must ask not only what is intentionally hidden, but why. What does the author want you to think, feel, or buy? Why would certain information be suppressed? We must help students develop a habit of inquiry and, when appropriate, skepticism.

I have found that this is the most difficult question to have students practice. That’s because in school we usually don’t give students fake information or bad logic. If we do, it’s with the intention of showing them the problem.

We might say, “Take a look at this article and see if you can find the unreliable sources.” Or we say, “Read this argument and highlight the evidence of author bias.” (Notice that in both of those statements, we’ve skipped Question #1 – What am I reading? – by telling the students the genre outright.) In the classroom we present texts in a way that is very specific and compartmentalized. We give students instructions in a vacuum.

But we know that hidden information is everywhere in our world outside school. And so do the students. We see faulty sources, suppressed truths, fake news, and author bias the second we pick up our phones. We know that the algorithms are working on us with every click.

Additionally, this hidden information is so hard to detect and name because we don’t know what we don’t know. And we don’t want to teach students to be completely paranoid, thinking that everything is hiding something and that all texts are out to get them. But we do want to make space for the hunch, the doubt, the question. We have to make space for the thought that pops up that says, Wait a minute, is this right? Is something missing here?

Using Reading Responses to Implement this Question

If you are new to my method of Reading Responses, please see my previous articles about it, as well as my book Reading with Presence. In short, a Reading Response consists of an original thought, a metacognitive category, a cited quote, and five sentences. In my class we do at least one a day, thus making it a constant, low-stakes writing practice.

To implement Question #3, I give students Reading Response categories such as:

- Author Bias

- Suspicious Sources

- Find the Faulty Logic

- Find the Funding

- Map the Algorithm

- Ethical Implications

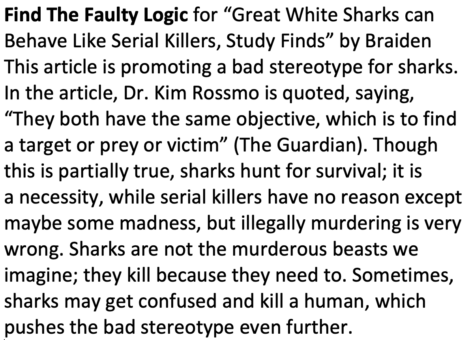

Each of these categories comes with some prompting questions to help students explore their thinking on the topic, and students can always choose the category they want to respond in. Think about how each of these categories connect to Question #3 – What is it hiding? Each category gives students space to explore something in the text that the author or creator did not want to reveal. The intention was to obscure. Look at the prompt and Braiden’s student example below for Find the Faulty Logic category.

Find the Faulty Logic

Are any of the arguments or techniques in this text faulty or inaccurate? Is there evidence of personal attacks, bandwagon thinking, or slippery-slope conclusions? Are there any other types of fallacies? What effect does this have within the text?

Here, Braiden is touching upon the basis of most stereotypes – a partial truth. In a conference, I would ask him if he thinks it is the researchers or the article who focus on this stereotype more. I would also ask how the title of the article draws in readers, what emotion is evoked, and if that is responsible journalism.

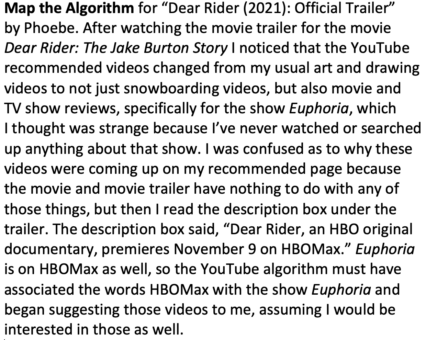

In this next example, Phoebe examines YouTube’s algorithm for her:

Map the Algorithm

As you read or view a piece of information onscreen, pause and look fully at the screen. Are there articles or videos suggested for you to view next? What does it look like these are about? What does this site predict about you? What intellectual or emotional direction is it funneling you toward?

* * * * *

Algorithms are designed to engage; the viewer is supposed to zone out. Helping students break into that pattern, even for just a few seconds, can help them become more critical consumers of texts.

* * * * *

We ask students constantly to explain what a text is “saying.” But in today’s world, we must go deeper – we must give them the tools to see beyond what a text is saying to what it is showing (Question #2) and then beyond that, to what a text is hiding.

We must make space for the inquiry, the hesitation, the hunch that pops up in their minds and asks “Is this true? Is there more?” This is not often done in schools. But to navigate the information that bombards them outside of school, students must have the skills to detect the bias, lie, or hidden intention.

Find all the Five Questions articles here.

Pre-order her new Heinemann book, Critical Reading in the Age of Disinformation: 5 Questions for Any Text, coming in November 2024. Learn more about her work at her website and read her many articles for MiddleWeb here.

This article is adapted in part from material in Critical Reading in the Age of Disinformation ©2024 Heinemann Publishers.