Writing: Blurring the Fiction/NonFiction Line

By Stephanie Farley

In the food world, the “bowl” I like to make for dinner – containing crispy rice, chopped raw vegetables, and a rotating menu of sauces, including guacamole, salsa verde, and pesto – is a melange of food-culture influences.

I’m not the only one to combine the best of all worlds. A new style has popped up in literature, as well, with the advent of romance/action books, like Rebecca Yarros’s The Fourth Wing, which was a bestseller, or a book I read a few weeks ago, Assistant to the Villain.

There are historical examples of literary fusion as well, like Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, a nonfiction account of a murder in which Capote used the fiction elements of plot, characterization, and setting to help tell the story.

A more recent example is Karl Ove Knausgaard’s opus, My Struggle, a work of fiction, but one whose protagonist is “Karl Ove Knausgaard” and that uses the minutiae of Knausgaard’s life and his reactions to it as “plot.”

Adding “big ideas” and “specific ideas” to essays

And, for years now, I’ve been teaching writing in a similarly hybrid fashion, in that I use elements of fiction to help students conceptualize and improve their nonfiction writing. Specifically, I’ve used the phrases “big idea” and “specific details” to characterize components of an essay, and I’ve explicitly taught “description” as a desirable approach for nonfiction assignments such as personal narratives and essays.

Further, I present these elements as virtually interchangeable: a big idea controls a five paragraph essay just as it guides the action of a story; specific details support the big idea in both fiction and nonfiction; and metaphoric language helps writers communicate more effectively regardless of genre.

The result, I’ve found, is that my students more readily grasp the foundational structures of writing and therefore aren’t as hesitant or reluctant to write in different formats. When they see that a “specific detail” = “example from text,” the notion of writing an essay isn’t so groan-inducing.

Differentiating process and products

As an interesting bonus, in true UDL style, this language has allowed me to easily differentiate both the process and products of writing based on student preferences and strengths. For example, in a class of 20 students, typically about half prefer to write fiction while the other half prefer nonfiction. With my hybrid methodology, I can achieve the same learning outcome for all students and allow them to write in their favored format.

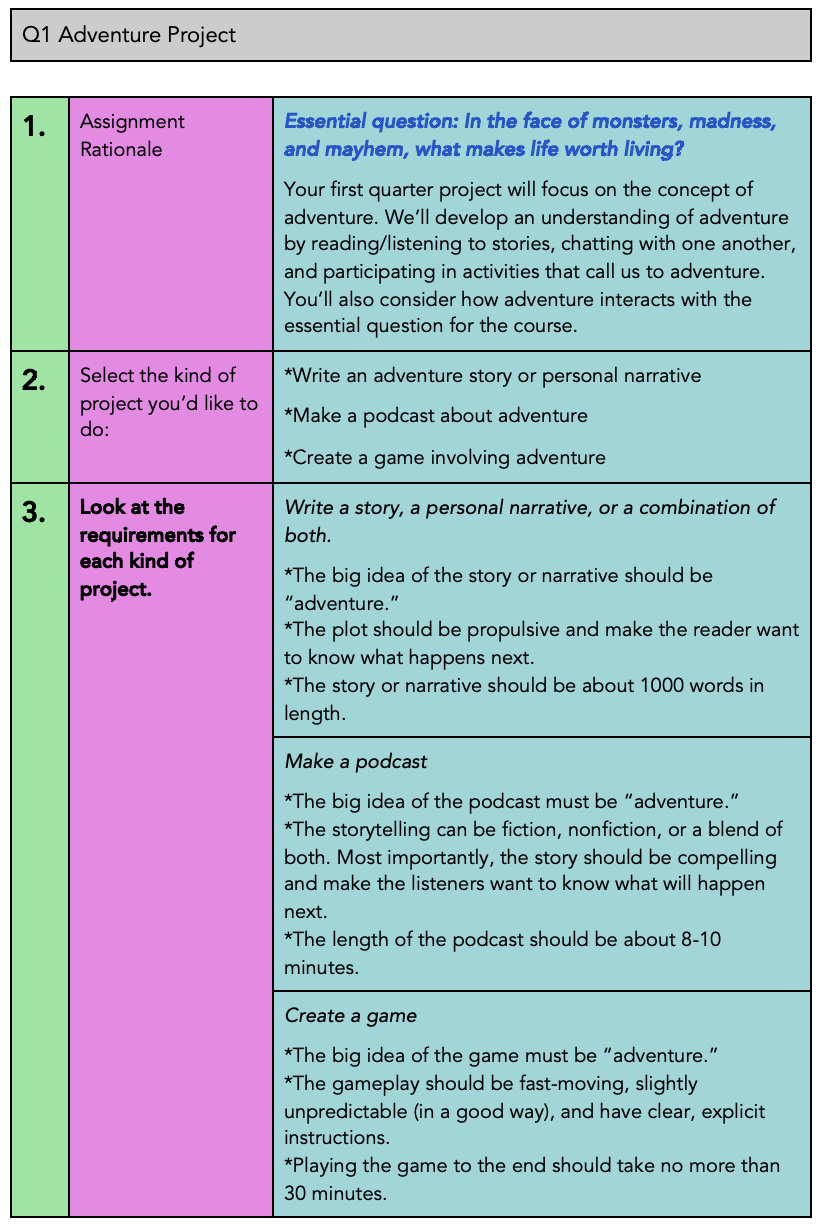

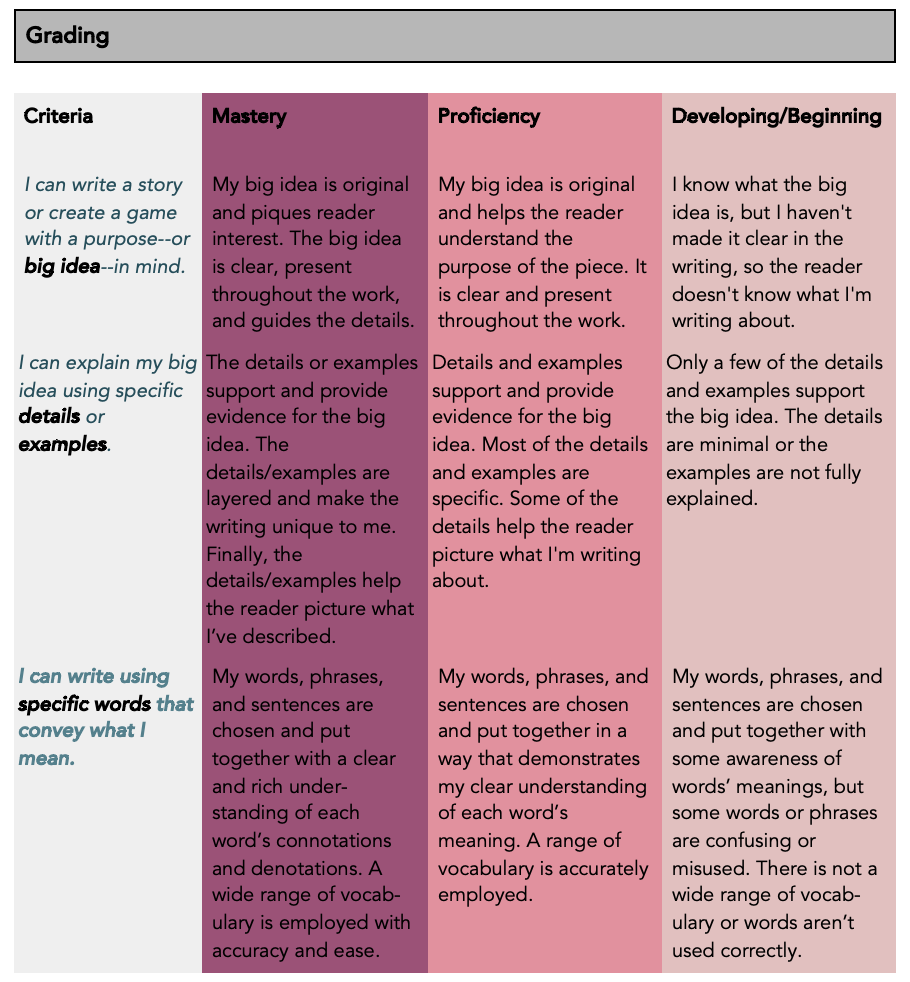

Here’s an example of an assignment to illustrate what I mean.

As you can see, the learning targets – represented by the criteria in the grading rubric – echo the language used when the class practiced these elements of writing. Indeed, there was explicit instruction and practice of “big idea,” “specific details,” and “specific words.”

We looked at models in the form of mentor texts; then students practiced each component through activities like: being assigned a big idea and having to produce details to support it; being assigned details and having to develop them into a story with a big idea; and being assigned specific words and having to use them creatively in a 5 sentence story. By the time this project was assigned, students were very clear about the kind of writing expected.

The blurring of fiction and nonfiction is also evident in the project style descriptions: I encouraged students to develop writing that was, perhaps, based on an event in their own life but fictionalized to make the story more “adventurous.” Alternately, they could entirely make up the plot but add in details that were true to their own experiences. Lastly, students had the option of writing “pure” fiction or nonfiction.

I’d be remiss not to mention that the success of this type of project requires that I’m super clear about two elements:

1. In terms of assessment, I need to know which learning targets I plan to evaluate before I even write the assignment. In other words, I have to engage in backwards planning so that I’m intentional about what students should know, do, and understand at the conclusion of the unit. Obviously the learning targets above combine “know” and “do.”

2. The curriculum is concept-based, which means that while I’m definitely evaluating skills at the end of the unit, ultimately my learning outcomes are based on enduring understandings of concepts within the discipline of English. That’s why each project style was about “adventure”: the enduring understanding that I aimed for students to develop through the unit was “Adventures make life worth living because they bring novelty and cultivate zest.” This is the “understand” part of the unit. It’s not graded, but I’ll see the understanding demonstrated in the writing as well as in students’ reflections on their writing.

Rethinking genre and form

The result of this type of curriculum and instruction, I’ve found, is that students are far more motivated to both practice and complete the project. Indeed, as Deborah Meier posited, they are inspired by the power of their own ideas. And why not? It’s fun to break the traditional rules of genre and form, and it’s really fun to develop a style that feels new and fresh!

For your next project in social studies, English, or history class, I encourage you to do a little action research by trying this method for yourself and seeing how the kids respond. Then, let me know! I’m excited to learn what happens.

Stephanie’s first book is Joyful Learning: Tools to Infuse Your 6-12 Classroom with Meaning, Relevance, and Fun (Routledge/Eye On Education, 2023). She has created professional development for schools around reading and curriculum and has coached teachers in instruction, lesson planning, feedback, and assessment. Visit her website Joyful Learning and find her other MiddleWeb articles here