Designing Group Work that Advances Learning

By Karin Hess

Most people can remember not-so-great experiences working in groups – one person dominates the conversation or is not respectful when interacting with others. Or one person gets stuck doing all the work, while everyone gets the credit. If you were willing to be the “workhorse” of the group, everyone wanted to be in your group. But group work doesn’t have to be that way. At it’s best, group work advances the learning of every student.

Most people can remember not-so-great experiences working in groups – one person dominates the conversation or is not respectful when interacting with others. Or one person gets stuck doing all the work, while everyone gets the credit. If you were willing to be the “workhorse” of the group, everyone wanted to be in your group. But group work doesn’t have to be that way. At it’s best, group work advances the learning of every student.

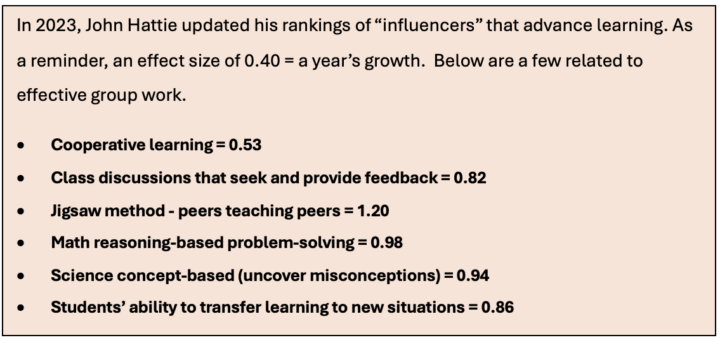

James Surowiecki in The Wisdom of Crowds (2005) states that under the right circumstances, groups are remarkably intelligent and are often smarter than the smartest people in them. In my books, I’ve summarized compelling research describing how well-structured small group work can result in students learning more, learning more quickly, and learning more deeply than each student can accomplish individually in the same amount of time.

For example, structured discourse within small groups engages more students simultaneously than whole class discussions ever could. Small-group problem solving (e.g., see this exemplars video) provides each member of the group with opportunities to integrate their prior knowledge and apply reasoning as they collaboratively complete open-ended tasks.

But it’s not simply collaboration that leads to deeper thinking. It’s actually dialogue that drives thinking within groups, large or small.

“Dialogue is one of the best vehicles for learning how to think, how to be reasonable, how to make moral decisions, and how understand another person’s point of view. Research also indicates that most teachers talk too much in the classroom and don’t wait long enough for students to respond. Dialogue is supremely flexible, instructional, collaborative, and rigorous … and one of the best ways for participants to learn good habits of thinking” (Nottingham, Nottingham, & Renton, 2017).

Collaborative discourse – especially in small, face-to-face groups – provides students with practice and models of what reasoning, giving critical feedback, and “showing your thinking” can actually look and sound like. It’s worth taking the time to teach students how to structure their feedback with actionable feedback stems (e.g., for gallery walks) or how to engage respectfully in collaborative discussions such as in this Edutopia video, Talk Moves.

Collaborative learning activities

Consider how each of the collaborative learning activities below support deeper reasoning and understanding for every member of the group.

►Send a Question/Problem/Claim: This strategy promotes team building by applying what has been learned. Each team “puts their heads together” to develop a question/problem/claim for another team to answer/solve/respond to. Before they send it to the another team, they must draft an acceptable response to their question, with supporting evidence. Then teams switch questions, develop answers to them, and send them back to the originators for feedback.

►Problem-solving Steps with Reasoning is structured for pairs of students to complete. After deciding what an open-ended problem is asking them to do, the pair completes each step (the how), explains their reasoning (the why), and tries to make broader connections using their collective prior knowledge.

►Collaborative Notetaking: Teachers can reduce the cognitive demand when trying to understand complex information by having students work in small groups to collaboratively develop notes using a shared outline document (e.g., using the TQE strategy or other brain-based notetaking strategies). Students build on their collective prior knowledge and make more – and more meaningful – connections to the new information through discussion and by considering the reasoning of others.

►Collaborative Error Analysis: This strategy pushes students to think critically about common errors and misconceptions by creating problems with errors for peers to evaluate, solve, and explain reasoning.

Round 1: students generate a problem or open-ended response related to the current unit of study, intentionally making an error or applying a misconception.

Round 2: groups rotate so they are looking at a problem with an incorrect solution generated by another group. Using a different-colored marker, they identify the error and resolve the problem.

Round 3: each group rotates one more time and critically analyzes the original problem and the corrected solution and determines if appropriate reasoning has been applied.

Using “GPS-I” to Structure Group Work

My collaboration acronym – GPS and I – is a useful way to remember the research related to designing successful and productive group collaborations.

G Stands for Group Processing

Group norms for short-term work will be similar to class rules, but it’s important for each group to adopt or adapt norms they all agree to follow (e.g., encourage everyone to contribute, take turns, no negative comments, each person takes a role to complete the work).

For longer-term projects (e.g., science or social studies investigations, writing a play), group members should establish norms to guide their time working together. Each time the group meets, they quickly review norms before getting started. Groups then clarify their tasks, set specific goals (such as using a SMART goals format), and self-assign roles to accomplish each of the tasks (such as in my PBL Team Activity Log).

Group members collaboratively reflect on how well they worked together each time: How did they resolve problems when they didn’t agree? Did they listen to suggestions that improved the quality of their work? Did everyone contribute? Using a quick strategy, such as using emotion emojis or “fist 5” (holding up 0 fingers as low to 5 fingers as high) to show how effectively they think their group worked together. Quick checks like these let the teacher know how well groups are functioning.

Finally, you may need to spend time guiding groups to collaboratively set broader (academic or mindfulness) goals for how they’ll work more effectively in future work sessions. Groups might also see a need to refine their group norms. Group processing ensures that the group – not the teacher – holds members accountable.

P Stands for Positive interdependence

“When students have trusted peers and solid relationships with their teachers, they are more likely to perceive the text and task to be less challenging and more doable. The ‘steepness’ of the learning experience will be judged to be less difficult because of the social support that the people around them provide. We can call this supportive presence” (Goldberg, 2025).

Positive interdependence – group members depending on each other to accomplish a shared goal – should be addressed in the group’s norms. Each member has a role and supports and encourages all other members in completing their individual roles and tasks. In turn, individual tasks contribute to the overall quality of the group’s final product. Positive interdependence can include how members interact with each other and how each person’s task depends on another completing their part (e.g., two students develop the story board, one person checks facts, while another drafts the shooting script for the documentary they are producing).

Interdependence can be created by having each student use a different resource or search for different pieces of information needed to solve a problem or complete the task. For example, one student is researching the context of an historical event while others are looking for differing perspectives, causes, or effects of the event. Then they combine and analyze the information together to develop a role play depicting the event.

S Stands for Simultaneous Engagement

Groups with too many members often have someone who becomes disengaged because tasks can be completed more easily by fewer people. When forming groups, consider how many different roles might be needed to complete the given tasks. Roles should demonstrate that everyone is working on something and contributing to the group’s shared goal.

Rather than teachers pre-assigning roles, teachers can suggest the roles needed and teams decide who will be responsible for each task. Another way to encourage students to self-assign roles is to have groups break tasks down to determine how each member can contribute. (For example, see my Collaborative Inquiry Plan).

Roles establish how each individual will be held accountable within the group. Simultaneous engagement means that everyone is working and contributing at the same time, not some members waiting around to do a task that comes at the end, like reporting the group’s progress. Simultaneous engagement and positive interdependence help students to learn the social skills that enable them to be emotionally and cognitively engaged, face-to-face or remotely.

I Stands for Individual Accountability

Each individual is held accountable for their contributions for successful completion of a shared task or goal. Thinking through the task requirements together helps students to clarify and take responsibility for answering these questions: what is my group supposed to do and how will I contribute so we can successfully accomplish it together?

Individual accountability – based on individual roles – addresses the age-old issue of grading group work. Individual contributions can be assessed separately from the group’s final product when rubrics are designed for both aspects of group work.

Teachers sometimes rotate the same roles, such as in ongoing science investigations throughout the year, so that by the end of the year, every student has demonstrated deeper knowledge and skills for each role (e.g., setting up equipment, collecting and graphing data, analyzing and writing up results). No one is held individually accountable for every role in each investigation. When students rotate roles, they can also teach peers what they learned about how to do that job effectively.

Assessing Individual and Group Responsibilities

Assessing collaboration can take a 3-pronged approach: Teacher observation and conferencing, peer feedback (e.g., Student-designed investigations with checkpoints), and self-assessment.

Collaboration Rubrics developed for K-12 schools by the New Hampshire Learning Initiative, describe performance levels for each grade span. Self-reflection and peer-assessments require students to provide their own supporting evidence to demonstrate that they have met expectations. The criterion for Self-Awareness addresses Individual Accountability within a group; the criterion for Monitoring and Adapting addresses Group Processing and Positive Interdependence within the group. Students use rubric descriptors to guide them in identifying appropriate examples of supporting evidence.

Final Tips on Structuring Collaboration, Engagement, and Meaningful Discourse

✻ Start with an authentic task worth doing.

If students are working in groups, they shouldn’t simply be working on low level tasks. Students can do many familiar routine tasks quite efficiently on their own. When you want students to do something challenging – perhaps more challenging than individual students are able to accomplish independently – it is an excellent opportunity to allow them to take some risks, struggle through a problem, and learn together as they construct deeper levels of meaning.

✻ Be sure that everyone has a job.

We can maximize simultaneous engagement and support deeper understanding when we structure group work for complex tasks requiring a stretch (far transfer). To do this well, we need to answer two questions: (1) What is the purpose (intended learning) of the project or performance-based task? (2) How many people will it take to successfully complete it? Educators can encourage the members of groups to self-assign roles for each job by guiding them to break down and define possible tasks that will lead to successful completion. Groups can assign roles based on individual unique skills or talent (e.g., artistic, public speaking), personal interests, or by lottery when all else fails.

✻ Establish parameters for completing the task.

We often give too much time and too little direction to what we expect students to do. Saying “discuss this with the person next to you” is not as clear as “you have one minute to discuss and write three reasons why______.” Whether it is a short, informal group sharing (e.g., Turn & Talk, Think-Pair-Share) or a longer performance or project-based task taking several days, giving students an estimated time frame and clear success criteria holds everyone accountable for managing the work, staying on task, and getting it done. Remember, you can always give groups more time if they need it.