Media Literacy: Teaching about Visual Media

We can and should teach students that films and other visual media can be “read” in a conscious and deliberate way (just like we read words) to extract meaning.

Filmmaker George Lucas has been a long time advocate for visual media education: “We must accept the fact that learning how to communicate with graphics, with music, with cinema, is just as important as communicating with words,” he says. “Understanding these rules is as important as learning how to make a sentence work.”

The important role of writing & storyboarding

Once their script/screenplay is final, students can begin the process of storyboarding the scenes. Many students are not familiar with the role of storyboarding. I want them to know that video games, TV commercials and movies are all storyboarded prior to production. (Today’s graphic novels are popular with Hollywood because potential studios can see the action and story already visualized, like a storyboard, in the graphic novel.)

Read a MiddleWeb book review about storyboarding.

Media Making & Meaning

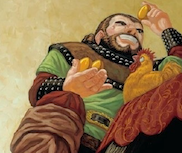

All media makers, from political campaign consultants to toy commercial producers, understand that there is a language to film and video. Here’s one example of a way to help students get meaning out of some of that language.

Filmmakers would tell you that when you position the camera to aim up at someone from a low angle, you’re also making that person more important. In the inverse, shooting down on someone takes their power away from them. With that simple understanding shared, I would turn students loose with newspapers and magazines and ask them to find photos that demonstrate the “high angle” and “low angle” techniques.

Where you put the camera has meaning. But there’s also meaning in the use of lighting, set design, sound, costume, makeup and more. These comprise “the languages of film.”

Surfacing visual clues

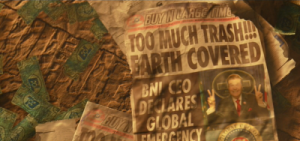

I like to use the opening scenes from the Pixar/Disney film Wall-E when I teach visual literacy to students in the middle grades.

• Does the action take place in the past, present or future: what are the clues?

• From what camera angle do we first see Wall E?

• Who is Wall-E’s sidekick? What role does he play?

• how does the music change as Wall E makes his way down the skyscraper of trash?

After the second viewing, participants share their observations, guided by the questions on the index cards. The second viewing responses make it a more enriching learning experience.

In this way, I am using these popular culture texts as the hook to understanding film technique and to teaching Common Core standards. After they’re comfortable, then we can move on to more complex films.

Language of Film resources & the Common Core

Recently, I unveiled a Language of Film web site. On this site, you’ll find several categories (cinematography, lighting, costumes, audio–just to name a few). Each category includes links to recent news stories, teaching curriculum and resources, as well as recommended texts and videos.

My goal is to make it easier for educators to integrate important 21st century skills into existing and developing curriculum. Did you know that the new Common Core Standards for the English Language Arts actually include specific references to film and the techniques students should know and understand?

Reading Standards for Literature: Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

CC.7.R.L.7 – Compare and contrast a story, drama, or poem to its audio, filmed, staged, or multimedia version, analyzing the effects of techniques unique to each medium (e.g., lighting, sound, color, or camera focus and angles in a film).

CC.8.R.L.7 – Analyze the extent to which a filmed or live production of a story or drama stays faithful to or departs from the text or script, evaluating the choice made by the director or actors.

With the buzz starting (already) about the Academy Awards (February 2013), movies, and those who make them, flim will be in the news frequently in the coming months. If you’re going to be teaching about film and/or film techniques, you’re sure to find plenty of material for student reading.

We all know that when we use video or film in the classroom, our students tend to sit up and pay attention. By going the extra mile, and teaching them screen education, we ensure that their viewing will not be passive, but rather active and critical.