My Chat with a STEM Teacher

A MiddleWeb Blog

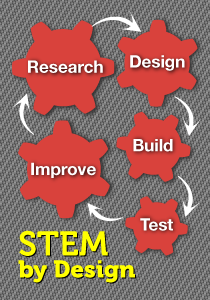

I passionately want STEM – with that all-important focus on teacher collaboration and content integration – to be a successful initiative. I want the big ideas that undergird STEM and the engineering design process to become the new normal for how we “do” school.

I passionately want STEM – with that all-important focus on teacher collaboration and content integration – to be a successful initiative. I want the big ideas that undergird STEM and the engineering design process to become the new normal for how we “do” school.

If you’re reading this blog, you likely agree. But for teachers, remaining faithful to STEM principles can be a tough challenge. What does it take to be successful and to hold the course? I want to share the story of one teacher’s journey with you.

The Engaging Youth through Engineering (EYE) process I described in an earlier post is one effective approach to meeting the STEM challenge. For six years this initiative of the Mobile (AL) Area Education Foundation has worked with teachers and business leaders to develop meaningful STEM modules and instructional practices for the middle grades.

Life science teacher Paige Till is one of the original teachers who partnered with EYE to launch the pilot program back in ’07. Recently I decided to follow up with Paige and see how she feels about this initiative after five years of implementing STEM lessons in her classroom. Here are some snippets from our chat with a few reflections of my own.

Anne: Tell us a bit about yourself – what is your teaching background and experience?

Paige: I have a BS degree in Elementary Education from the University of Southern Mississippi. I have taught math, science, language arts, social studies, and an elective called Art in Science. This is my 18th year of teaching, and the third state/school district in which I’ve taught.

Over the past five years Paige has been piloting, implementing, and helping to improve STEM modules developed by the EYE team. In fact, she and other teachers meet with the curriculum developers and writers before, during, and after implementing each module and provide vital feedback and suggestions.

Anne: How is the STEM process is working?

Paige: In the beginning, I was convinced that this was another program that we (teachers) would put our heart and soul into for three years and then it would be abandoned just as we began to see results. However, as we went through the first couple of years it became apparent that this program was different. The developers listened to the teachers’ suggestions, helped with problem solving, and gave the support promised. It has been a process of open communication between the teachers and the developers.

• Involve all participating teachers from the first as part of the development team.

• Get their input and incorporate their feedback and ideas throughout the process.

• Honor their knowledge and understanding of teaching, and provide support as they begin changing some of the ways they normally do business.

Since Paige has 5 years of experience in facilitating an intensive STEM module each quarter, I wondered what Paige thinks about the STEM curriculum.

Anne: How are these lessons different from what teachers generally already do in their classrooms?

Paige: These lessons are detailed, comprehensive, and interesting to the students. I find that these lessons are close enough to reality that the students seem to buy into them.

Aha! That’s the idea behind STEM – to connect learning to reality. Every year I taught I heard these questions from my students: “Why are we learning this? When will I ever need to know this?” The answer becomes self-explanatory as students use their lesson content to solve real problems.

Anne: Which module do you especially like?

In To Puppies and Beyond, students focus on connections and contrasts between genetic engineering and selective breeding. Other modules Paige works with include Catch Me if You Can in which kids design and build “clot catchers” to solve a blood clot problem; and Eye on Mars in which kids design and build high efficiency growth systems to help with growing plants on Mars. All link students to what’s going on in the real world of science and engineering.

Anne: How have your students responded to these STEM lessons?

Paige: It is really neat to watch the kids problem solve and debate the different ideas presented by group members. I have noticed that the students who are always uninterested and non-participatory tend to get involved and sometimes even show their creativity or leadership skills. I also have noticed that many times my special education students shine with great ideas – sometimes the best of the bunch.

Here’s another great takeaway from Paige: STEM definitely does level the playing field and allow all students to make valuable contributions to the project. To provide opportunity for full student participation, students work in teams. They learn productive teamwork skills and ways of interacting. STEM lessons call for a variety of talents and abilities, and team members all have a chance to shine in some area of the project as they work together in researching, developing, creating, constructing, and testing their products.

Anne: What do you think has been the strongest part of this STEM curriculum?

Paige: I believe that this curriculum has helped to make the math and science connection clear to students.

The idea of cross-curricular collaboration on a project is sometimes hard for teachers to wrap their heads around. Teaching has historically been a silo experience, with different subjects having no apparent connections with other subjects from the students’ standpoint. When lessons can be arranged so that students are working on aspects of the same project in both math and science class, then kids really sit up and take notice.

Anne: What do you value most about a STEM lesson?

Paige: When a student says, “This is like what we are doing in math class.” That moment always makes me smile, because I know they get the connection.

The students are seeing the interdisciplinary connections. Maybe that’s one of the most valuable aspects of STEM for our students. STEM offers many ways to make those connections naturally, in real-world contexts.

Anne: Is there something that does not work well with the STEM lessons?

In today’s world, with so much emphasis on testing specific objectives, connecting STEM content to the required curriculum is especially important. Teachers feel the constant pressure to meet the prescribed objectives. When the EYE team designs a module, the developers place the math and science objectives side by side for the quarter in which that module will be taught. Often engineers and professors meet with the developers to help think through and generate problems that kids could tackle to address these specific objectives. This is one of the most intense and time-consuming parts of the curriculum development process.

Anne: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Paige: I have really enjoyed being a part of the process of developing this curriculum. For teachers who are beginning to implement, I think the most important thing is to establish procedures for everything the students will need to do. This makes things go much smoother.

How do teachers organize to teach STEM? How can schools and systems help with these procedures and organization? Stay tuned! You’ll see that in an upcoming post.

“I have noticed that the students who are always uninterested and non-participatory tend to get involved and sometimes even show their creativity or leadership skills. I also have noticed that many times my special education students shine with great ideas – sometimes the best of the bunch.”

I have seen this for myself and heard many similar reflections from teachers and colleagues involved in developing and integrating the STEM fields via engineering projects. Such reports from the field suggest we are reaching students who are difficult to reach, and that their involvement in the class is enriching their own and others’ learning of important content. (Of couse, they also seem to be learning important social and life lessons, as well.) How powerful and motivating for students *and* teachers — as well as those of us who are fortunate to work behind the scenes and collaborate with teachers like Paige and her colleagues!

I, too, have seen students who are normally complacent and disengaged come alive when faced with a real life challenge and an opportunity to participate in a way that makes sense to them. Kids who have the perceptual skills to see how things fit together and those who can analyze and solve problems in a 3-D world have a chance to shine. Often paper and pencil is just not their “thing.” And learning how to work with classmates in teams helps, because there’s so much more room for participation in a team of 4 than in a classroom of 28. STEM just works, doesn’t it?