Confessions of a Struggling Student (Me)

A MiddleWeb Blog

Then there are the students who, sadly, don’t know how to interact with their peers, and so group work is a challenge for us when we pick kids to work together.

But the behavior I worry about the most is found in the silent, apathetic student, who may be concealing a brilliant and creative mind.

So, what do we do as teachers? How do we help all these different kids whose behaviors affect not only their classroom performance, but our frustration levels as we search and search and feel like we’ve tried everything?

Maybe it will help us to remember a time when we struggled ourselves. I don’t have to think back very far (a couple of days actually!) — to call up those feelings. So let me tap into my current personal experience and share some of what is helping me, the student whose behavior is affecting her classroom performance.

Learning that put me outside my comfort zone

Recently, I was honored to be chosen to be involved in a STEM grant in my district. As part of this professional opportunity, I would take online math courses for 18 months, get paid a stipend, be given a MacBook and an iPod Touch, and spend time each week working with other colleagues as we solved math challenges and created projects for our students.

Our first “Kick Off” in August had me excited (like the first day of school for our students) as we met one another and were provided with a schedule of our two days of activities to prepare us for our coursework. We had been given our shoulder bag full of technology tools earlier in the summer, and I was so excited about learning how to use them. (I felt like our students with their backpacks filled with 3-ring binders, pens, pencils, paper, and notebooks).

I met my group — the teachers from throughout my state with whom I would be sharing my work for the next year and a half, as well as our facilitator, Sheree. I thought of this as my homeroom; they were the kids from different neighborhoods and Sheree was our homeroom teacher. I eagerly tried learning names and faces, and felt a little nervous. Then I saw a teacher from my building join our group, a familiar face. Is this how kids feel on the first day of school?

What it feels like to wait for help

I was reminded of my students who are talking in class while we’re teaching. As my fellow classmate tried to help me get caught up, I realized I was dragging her down, and our talking was distracting the other students.

As we continued to further update our laptops, I noticed there were “assistants” circulating the room helping other struggling students. I joined the signaling but the help was slow in coming. I became jealous and impatient because I couldn’t go further without their help. I wondered if this is how my students back at school felt when there were two teachers or a teacher and a para-professional, and 24 of them waiting to get help.

Eventually, thankfully, I got the help and completed my software updates. This was our last class for the day, ending at 9 p.m. I was so tired that night, but I didn’t sleep well, knowing that classes were starting the next morning at 8:45.

The next day was equally challenging: incorporating math, using the iPod Touch to videotape our students, and learning how to do a student interview. What saved me that day were two teachers who invited me to join their group and helped me navigate the iPod movie making. They reminded me of the kind and thoughtful kids who offer to help their classmates back at school. I actually gained confidence as they guided me to make videos of them.

Walking a mile in my struggling students’ shoes

As I read, reread and highlighted the class notes I began to wonder, “Do I have some kind of math disability or reading comprehension weakness?” I read the words, I listened to the video, I even tried doing the problems along with the video, but still, nothing. No connection, no understanding, no lightbulb switching on or Aha moment. My mind was blank.

Then I did what my students who get frustrated sometimes do — I shut down. I logged off our website, angrily shoved all my notes into my book bag, and did all kinds of avoidance things: ate chocolate, drank MORE coffee, called friends and patted my kitties. Then this sick feeling came over me: if I don’t do this work, I have to give back the beautiful technology tools, I won’t receive my stipend, and (worst of all) I’ll let my math partner Aileen down.

I’ve had kids ask me as early as the first semester, “If I don’t pass, will I get kept back?” That’s how I felt: What if I fail?

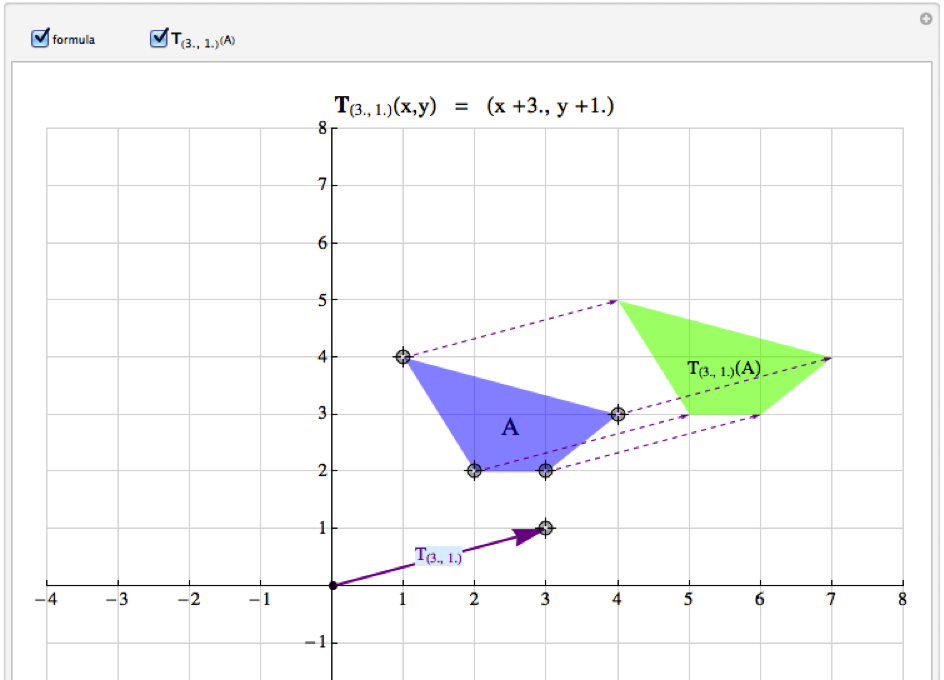

This is the kind of work I need to understand each week:

T3(x) = x + 3: T(a;b)(x; y) = (x + a; y + b): T( 4 , 1 ) (x, y) = (x+4, y+1)

Yikes!

Here are some supports that are helping

I am very lucky that my math partner Aileen and two school colleagues, Lisa, another 6th grade teacher, and 7th grade teacher Carolina, are part of this grant work. We are required to meet weekly, and so Carolina, who tutors adults as her second job, offered to tutor us each week. She puts each problem on the board and explains it and clarifies it as we work to solve it with her guidance. Does this sound like after school help?

In addition to helping me understand the math, Aileen and Lisa help me navigate the laptop (we also have to format our work into PDFs, with graphs, etc.). Since Aileen and I co-teach together, she will make connections for me between what we’re learning in our STEM class and what we’re teaching our sixth graders. Oftentimes when we plan our lessons, we are also incorporating our interviews with students into our planning discussions. As a student, I am being called upon to “make connections to learning,” just as I expect (hope) my students will do.

Learning by doing

When I first started posting my assignments on our STEM grant platform, I would get e-mails scolding me for not posting in the right place or in the right format. This just added to my frustration. Pearl, our grant’s technology guru, offered to come to my school and work with me 1:1 until I understood what to do.

I am not joking that I cried with joy as she guided my hand over the MacBook touchpad and showed me how to click using my thumb (I learned clicking with a mouse on my old Gateway) and to scroll using my fingers. She had me practice as she guided me verbally on the various steps needed to post correctly, and made me practice until I was successful.

Putting my teacher hat back on…

Here is what I’ve learned as a student who struggles:

Having support from peers – Our group posts our assignments to a Forum. Here people share their answers and voice their frustrations. Sheree again encourages, and she creates an environment that is supportive and respectful. In our classroom Aileen and I have the students sit in pairs. We encourage peer sharing and completing math investigations together. In addition, when we have after school help, we often have Grade 7 students who love to tutor the “new 6th graders”.

Demonstration + Practice = Confidence – I realized I wasn’t any different from my students who struggled with new material: I needed someone to show me and then let me practice. The more I practiced the more confident I became.

Kids often don’t believe their teachers have ever failed at anything. When a student shuts down, it helps to share your own stories of when you struggled (we’ve all had experiences of being challenged with learning something new: maybe trying to drive a car with a 5-speed manual transmission, or how to do Yoga or Zumba). Sharing the feelings of frustration or even embarrassment with your students is immensely empowering for them.

Kids may not join because they can’t contribute. When kids don’t want to join in a group, there can be factors we aren’t even aware of: they feel inadequate, they feel they can’t contribute to their group. (I feel this way on a regular basis when I meet with my fellow Math Musketeers, all certified middle school math teachers, and me, the special ed teacher.) Students may be having difficulty socially with another member of the group; perhaps they used to be friends in elementary school but have now drifted apart.

Some of our students are on the Autism Spectrum or have Non Verbal Learning Disabilities. The thought of being in a group and being forced to socialize is as challenging for them as my course instructor asking me to present to my fellow teachers. My co-teacher teammates often give kids a choice if they come to us privately, and are very uncomfortable working in a group. We can check with the school psychologist to guide reluctant group members during counseling time, but if they aren’t quite ready, we allow them to work independently.

The most valuable lesson

I realize that the most valuable lesson I’ve learned from this STEM grant wasn’t how to use the laptop, or navigate the math; it’s how I can better approach my students whose behaviors affect their classroom performance. I’ve broadened my perspective — I’m no longer seeing everything from the teacher’s perch. I’m also a fellow student, a person who sometimes struggles with learning and needs an understanding hand to guide me as I learn new ways to click.

Teaching is the highest form of learning. If you allow your students to teach as a way of learning you have created an environment that supports learning as a self sustaining model. . Following the class wide peer tutoring model builds more skills than just academics. It develops social intelligence, therefor, changing academics will also change the challenging behaviors in your classroom as well.

Eva,

Thank-you so much for your comments; social intelligence is so important for kids. It provides an opportunity for them to learn and develop empathy as well, a priceless lesson they will use for the rest of their lives. I would love to hear more about how you use peer tutoring with your students.

I had a visceral reaction to this article. I could feel your pain. As a special education teacher, it is easy to relate to the scenario you paint. My career has not provided the opportunities to “embrace” the technology of today. Being unfamiliar with the tools as well as the content of a course creates the perfect horror story. I, too, could only have ended up in such a class by accident. Imagine what those kids who struggle every day feel like; it ‘s no wonder they find different ways to check out.

Cynthia,

Thank-you so very much for your honesty and heartfelt comments. When our new schools were first built 11 years ago, I went out and bought a computer identical to the one I would be using in my classroom for home use. I didn’t even know how to write or send an e-mail.My students taught me so much and were incredibly patient with me. I felt like the kid who learns how to drive a car and wants her parents to buy the car she’s learning on through driver ed. Thank-you so much for reading our blog and sharing your thoughts.