STEM Teaching Means Teaming

My guest blogger this week is Caroline (Cal) Goode. Over a year ago, Cal joined me in writing STEM lessons for Engaging Youth through Engineering (EYE) and the large Mobile County Public School System. What a valuable colleague she is, whether we are working together virtually or face to face to create strong middle school STEM lessons.

Great science teaching is Cal’s trademark. She was a Christa McAuliffe Center Teacher of the Year and also a Challenger Center for Space Education Teacher of the Year. Currently Cal is the State Coordinator for NSTA’s Science Matters Massachusetts. I am most fascinated by Cal’s work with the New Teacher Center’s e-Mentoring for Student Success program. As a STEM Learning Consultant, Cal works with teachers virtually and mentors them through challenges with STEM teaching (among other teaching challenges.) I asked her to write about her eMentoring in this blog post. Take it away, Cal!

STEM Students Learn Best in Collaborative Teams

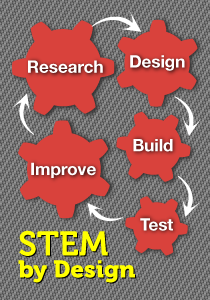

As I skimmed the recently published Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) the other day, I realized that the inclusion of STEM’s “E” (engineering) throughout the standards will be a game-changer for both new and veteran science teachers.

As an online mentor for The New Teacher Center in Santa Cruz, CA, I work frequently with novice and out-of-field teachers involved in STEM-related teaching. I’m able to share my experiences, strategies and best practices with as many as eight new teachers each year. In our private discussion area, called Our Place, mentees can openly share frustrations, ask for help and ideas, and know that they are not alone. Over time, as you might imagine, I’ve gained some insight into STEM teacher preparedness.

Creating a strong, harmonious STEM classroom will require many different teaching capacities, including STEM-specific classroom management skills that in my experience are not routinely found in middle grades teachers’ pedagogical toolkits — especially those of novices.

Expectations for 21st Century learners

Let’s think about where a new teacher begins to acquire the skills and tools she needs to provide today’s students with the ability to become successful members of the 21st century workforce.

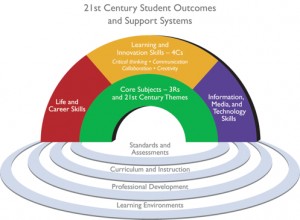

The Framework for 21st Century Learning overview outlines the student outcomes for success in today’s global markets. First and foremost, STEM teachers will need to build a strong foundation for what the framework labels as “Learning and Innovation Skills.” These are the skills students will need to pursue careers in the “increasingly complex life and work environments in today’s world.”

As I think about NGSS and the engineering design process, Communication & Collaboration immediately leap to the top of the toolbox for me. Without the ability to work as a team and communicate effectively, the skills associated with Creativity & Innovation and Critical Thinking & Problem Solving will be very difficult to achieve.

Teamwork is a top priority in business and industry today, and if we are not teaching the art of collaboration in our classrooms, we are failing to prepare our students for success in the today’s world. Anne Jolly’s MiddleWeb blog post “Effective Student STEM Teams” details the importance of teamwork, and I recommend that every teacher download her “Seven Student Teaming Tips and Tools” guide to assist as they integrate collaboration skills into their classrooms.

Knowing how to get students to work together effectively is the first and most basic tool every in STEM teacher’s best-practice toolkit.

The basics of student collaboration

“As a new STEM teacher, what comes to your mind when you hear the words collaboration or teamwork?” When I ask my e-mentees this question, I get responses that run the gamut from “working in groups” or “working with a partner” all the way to “losing control,” “too much chaos” and “too much bickering.”

So what are the basics? Let me share the model that I found works best for me and see what you think. After trying groups of 2, 3, 4, and 5, I found that the 6/3 model was the most effective because it allowed teams (teams, not groups) of students to come together in a grouping of 6 for brainstorming and idea-sharing and to split off into subgroups of 3 for labs and more focused work. The beauty of this model is that when the subgroups come back together, they are able share, communicate, and learn from each other. (Here’s a detailed description of the 6/3 Model.)

Here’s what I say to my mentees: Gone are the days when talking to another student or sharing work was a punishable offense. We are working with students who are used to speaking their minds, questioning things they don’t understand (or sometimes don’t agree with). The 21st century student comes to us seeking structure and knowledge, not as vessels to be filled by the transfer of our knowledge into their minds.

So I’ve got the 6/3 model – but I’ve got 30 kids!

Many teachers wonder, of course, how in the world they’ll manage a class of 30 or so students working together. It’s a great question, and I quickly admit that teaching and modeling teamwork with middle school students takes time. These are some tips I offer:

• Teams should be heterogeneously grouped. Taking the time and effort to look at your student’s ability levels helps to insure that your classroom reflects the “all students can learn” philosophy. You will be amazed at the relationships that form among students of varying talents and experience when all ability levels come together to solve problems and think creatively.

• Establish protocols. Before embarking on the road to teamwork, think about how comfortable you are with student interaction. When you have 30+ students brainstorming, discussing, sharing and working, expect the noise level in the classroom to rise. Giving my students fair warning that when working as a team they are to use their “one-foot voices” (meaning that their voice should only be heard by a person one foot away) has helped to keep me in my comfort zone. When the noise level rises, be ready to remind the too-loud team or teams to use their “one foot voice.” If this isn’t sinking in, feel free to shut the lab or discussion down.

• Assign team roles. In order to function as a “team,” students need to know that everyone contributes to the end product. By defining roles, you are giving each member of team ownership in the work to be done. Roles change weekly so that each member of the team assumes responsibility of the work on a rotating basis. This system prevents the shy, quiet student from being shut down by the more aggressive students on the team. Everyone has a voice and everyone is respected.

Creating an effective STEM classroom that has rich content, incorporates 21st century skills, and is inquiry-based will be a challenge for both new and veteran teachers, but mastering the process of effective teaming and collaboration is a tremendous first “tool” for the teacher’s STEM toolkit.

Developing a collaborative model that works for a particular teacher in a particular classroom in a particular school takes time. I spent many years “stealing from the best” to tweak and develop the model that worked well for me. Every successful STEM teacher will do the same. I hope these ideas and resources will help accelerate the process!

Ah, Cal – you are so right about the teamwork. Students may have a good handle the academics, but unless they can work together as colleagues to use that knowledge to create, design, and engineer products, much of that knowledge will be useless in the practical sense.

I am fascinated by the e-Mentoring idea. So many teachers are trying to implement STEM lessons alone and need someone to collaborate with. You provide them with ongoing help. There’s got to be something there for school systems to consider in helping teachers to implement STEM.

Good job!

Cal,

What a helpful and practical guide for teachers who want to help their students become better at teamwork! I know teamwork WORKS on a lot of different levels, but I also have seen some teachers struggle just to get their students to behave once they are in a team situation. In such situations, I see that the teacher’s natural impulse is often to minimize the number of times students collaborate, to minimize the difficulty and maximize appropriate control over classroom behaviors.And I empathize with that response when the situation is extreme and the class truly does seem in danger of spiraling out of control.

I have been wondering about whether there are more effective (but realistic) approaches to take. I have some thoughts – but I would love to know what others think! What has worked for them?

Here are some of my thoughts:

* Would it work to start modestly, with interesting but extremely short activities that require pairs of students to think and work together? Maybe Think-Pair-Share is the right starting point, with a gradual increase over a few weeks to include Think-Pair-“Do Something”-Share…and then Think-Move-to-Triads-Do-Share….Or something along those lines. The activity should be engaging but not prone to distract students. Maybe an observation exercise, where students are looking at something (a shell? a mixture of powders? something curriculum-oriented) and first making their own observations and then comparing, trying to collectively come up with as many detailed and unique observations as possible? (This could then lead to some aspect of the content for the day.)

* I also know from our colleague Deb Dempsey that taking the time in the start of the year to create a culture of collaboration is important. Before she retired from the classroom, she would do this via community meeting. Students practice certain protocols for sharing ideas, but the information is more on a light, personal level (in the beginning). The message is that the people, as well as their ideas, are important, and that everyone has a chance to be heard. This carries over into the curriculum (and a small action research project that she conducted showed better behaviors and fewer negative incidents outside the classroom with students who had experienced community meeting, over a control group.)

However, Deb was in a more-or-less self-contained classroom situation, and had a little more flexibility than the teacher who has 45 minutes per lesson. Any suggestions for tapping into community meeting, or otherwise creating a classroom culture of collaboration, in these latter types of classrooms?

*Maintaining a culture of collaboration is also important – Making Learning Visible (a project at Harvard’s Project Zero) has some info on that, with the fundamental approach being that teachers and students examine documentation of what’s happening in groups as they learn and create, and reflect back on that. As students and teachers engage in narratives of the learning process, the documents – images, quotations, works-in-progress, final work -consciously focuses on the contributions that individuals make to the group. I think this kind of mirror is an important aspect of maintaining culture.

Of course, this is all very hard to do – especially when we are teaching something for the first, second, or even third time.

So…I just wonder…Cal, Anne, others – are my ideas too pie-in-the sky for reality? If so, what might them back down to earth?

Carolyn, Thank you for your post and you do make some good points that I’d like to address. As a middle school teacher who what began with “cooperative learning” in the early 1990’s, to what is now know as, collaboration, I can attest that what works for me may not work for you.. Believe it or not, I continued to revise and tweak my original model until the day I left the classroom and began consulting, all the while taking what I could get from teacher leaders in the many hours each summer of professional development. To be honest, the “think-pair-share” model was already a part of my language arts and science classroom strategies. At that time, all of my “hands-on”/constructivist activities were done in pairs. Like our friend, Deb Dempsey, I began my first few years of teaching in a self-contained classroom and found it was much easier to set up and model working as partners than when I moved to the middle school to teach language arts and science. The one most thing I missed in this transition was being able to have my community of learners. How in the world was I going to establish such a community with each 45-minute class of student?. I came to realize that, yes, I could still bring that “community” feeling into my middle school classrom through the teamwork lens. Just because there wasn’t time for our informal discussions didn’t mean that I couldn’t develop teamwork protocols and procedures that would teach my students the values that teamwork instills such as, listening with respect to others ideas and presentations, being able to contribute to group work as an active participant, and accepting that it isn’t always “all about ME” (this is a hard concept to grasp for middle schoolers). The difference in middle school is that you have to jump right into it and allow the students to learn on the job. As you said, this may be difficult for teachers who are not experienced, but it is not impossible. Yes, begin slowly with the “pair-share-think” strategy and with mini-labs and activities and know that this may be all you can do the first year. Hopefully, as you begin to build confidence in yourself and your students, you will be able to move to the next level.

As for the teacher who cannot cope with “letting go” or being in control, I say it is time for change. There is no way we can prepare our students for the global marketplace if we are still teaching them like we did when we went to school. If a teacher is still keeping kids in rows, is still the “giver of knowledge”, and worries that things will spiral out of control, then it is time for the administration to step up and provide opportunities for these teachers to receive the training and modeling they need. It is critical that we, as teachers, move from the passive classroom to the active classroom. In other words, be a 21st century teacher to our 21st century children. This will not happen overnight, but we have to start somewhere, don’t we?

The Making Learning Visible project sounds doable and valuable but something that teachers should be doing naturally in the classrooms anyway. I know, sad to say, that this isn’t always being done but I know that effective teachers, like the Deb Dempsey’s of the world, do this naturally. Reflection through discussion and writing is a key component to learning, both for students and teachers, but seems to be the one step of the teaching and learning process that we fail to achieve. I think there are several factors in play here–time constraints, lack of teacher knowledge of effective reflective strategies, and the old assumption that the almighty written test or quiz sums it up. We both know that is not true. Even in the best professional development programs, I find it hard to recall having the presenter take the time to model reflection techniques. As a presenter, this is something I have to address. After all, how can I expect teachers to use reflection with their students when I am not giving them the resources and practice to do so?

So to answer your question about “pie in the sky” vs. reality, the answer is no, Carolyn. Your thoughts need to become reality:)