Teaching Boys: the STEM Solution

A MiddleWeb Blog

I strongly advocate for more STEM success and preparation for girls. I’ve written blog posts on girls and STEM, and I’ve scattered references to the need for more attention to STEM girls in other posts. However – I have to tell you – I’m the mother of three boys (young men now) and I harbor passionate feelings about our boys and their educational difficulties as well.

During my 16 years as a middle school teacher, my heart went out to all of those squirmy, impulsive young men who brought so much life and energy (and occasional distractions) to my science classes.

The fact of the matter is: many boys are not thriving in school. Our boys are at an educational disadvantage from the time they enter kindergarten. They come to us hardwired with traits that don’t fit into traditional views of how “model” students should behave and perform in class.

Andrea Schneider, a mother of 2 boys and a psychotherapist, puts it this way:

Our culture at large needs to do more to support boys and their unique hardwiring in educational settings. Although my sons have the advantage of great teachers and a nationally respected school district, the structure of our educational system does not favor boys’ unique learning styles . . . We, as a nation, are failing our young men in the area of educational support. And we need to change that.”

Are we failing our boys? Let’s look at a couple of those educationally disadvantageous traits with which our boys are “gifted.” (Note: these traits and needs are often characteristic of girls as well. However, for the purpose of this post, I’m keeping the focus on our young men.)

The hardwire problem for boys:

• Boys show more areas in the brain dedicated to spatial-mechanical strengths, and fewer dedicated to verbal areas. They generally start slower in the areas of reading and writing. Since typical elementary classrooms are primarily language-based and lots of boys lack the fluency to be as successful as girls, many develop identity problems with regard to school.

• Boys are more active and have trouble sitting still for long periods of time. They are more alert when they are standing and moving. Pull up a mental image of our traditional middle school classes where students may be expected to sit quietly in ruler-straight rows hour after hour during the day. Heck, that scares me, and I like to sit quietly. Possibly the most frustrating words a boy can hear is “Sit down!”

• Boys are generally hardwired to be kinesthetic learners. They learn best through hands-on experiences – through touching and moving. They are less able to focus when forced to sit still and learn through static activities.

• Boys are more aggressive and competitive, and tend to be less collaborative than girls are. They have more difficulty with impulse control.

• Boys are relational. Findings show that boys learn best when engaged in a positive, trusting relationship with their teachers.

• Boys learn best when the have a real reason for learning something. In fact, boys need a reason to engage in a learning task that goes beyond, “Because I said so.”

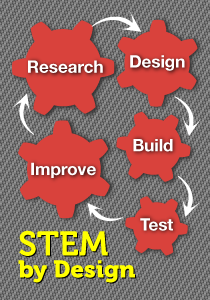

The STEM learning solution:

So what’s a teacher to do? Or a school? Or a school system? Frankly, the recommendations for strategies to meet the educational needs of boys practically scream, STEM! STEM! STEM! Take a look at what the research says.

Provide a high-energy classroom where boys can be energized and motivated by movement. Ditch the teacher-centered approach with lots of teacher talk, note-taking, and quiet studying. Instead, imagine STEM lessons in which students learn about forms of energy and motion by building and testing catapults, rocket cars, and rollercoasters. A good fit for boys? Oh, yes.

Design lessons that provide students with real world applications. Establish an authentic purpose and a meaningful, real-life connection for what you ask students to learn. Boys tend to ask, “Why do I need to know this?” They need clear linkages between what they are learning and their lives outside of school. That’s one of the requirements for an authentic STEM lesson – solving a real-world problem.

Involve students in teamwork. Teamwork is especially important for boys as they learn to cooperate and develop camaraderie. (Tip: single-gender team groupings may sometimes be beneficial.) Recall that boys tend to have a thirst for competition as well. STEM lessons that require a combination of competition and teamwork tend to be most engaging for boys.

Add to those recommendations these 8 categories of lessons that succeed in teaching boys (featured in The Atlantic). Notice the close correlation between these lessons and STEM lessons.

1. Lessons that result in an end product

2. Lessons that are structured as competitive games

3. Lessons requiring motor activity

4. Lessons requiring boys to assume responsibility for the learning of others

5. Lessons that require boys to address open questions or unsolved problems

6. Lessons that require a combination of competition and teamwork

7. Lessons that focus on independent, personal discovery and realization

8. Lessons that introduce novelty or surprise

That looks like a checklist for STEM lesson design to me. What might a great learning activity for boys look like? A STEM lesson!

STEM takes advantage of boys’ high-energy, movement-driven learning styles. STEM allows choice, problem-solving, authentic applications, and teamwork. STEM lessons allow teachers to move around and interact with students, and offer more opportunity for building relationships.

I offer to you the suggestion that STEM is the perfect fit for the educational needs of our boys. STEM lessons are the ideal learning solution. Let’s advocate for effective STEM programs with increasing fervor.

Please don’t think I’m overlooking the girls. I’ve written about Girls and STEM here and here. In reality – STEM is a great solution for all of our students!

Extra resources

You can read more about boys’ learning needs in these articles. Much of my information came from these sites.

10 Essential Strategies for Teaching Boys Effectively

How Boys’ Learning Styles Differ (and How We Can Support Them)

Photo: Motlow CC

Thanks for a great article. As the mother of 4 lively sons (all very different from each other) I appreciate the points you are making. Those of us who have parented boys have an edge on understanding how real the learning needs of young men are. This was not a discussion we ever had in “teacher school”!.

I love the idea of using STEM subjects to engage energetic students. I only wish you had not used boys, specifically. I have an energetic daughter who thrives on STEM subjects! It will be a sign of growth in the teaching community when everyone targets behavior issues rather than gender issues.

STEM, really is lacking if it does not include the A for art, making it STEAM. Just the idea of STEAM, creates energy and all kinds of possibilities! I totally agree with Judy, gender really is not the issue.

I am a high school science teacher, and one class I teach is generally made up of high risk for dropout BOYS! I’ve always said these guys don’t buy in to a class in which a woman stands in front telling them how to fill out paperwork. Their fathers and male role models don’t do such things. Their male role models build engines, rescue stuck jeeps using winches, and hunt and fish. Sometimes their male role models play ball or ride dirt bikes. Good article.

Barney, I know about those lively sons, for sure. What I honestly did not realize was the difference in the biology of the male brain. (Some of those articles I posted go into that a bit.) We are really doing our boys an injustice by conform to and perform in a traditional stereotypical classroom. Girls do work better within that stereotype, although we don’t do them any favors by not engaging them in active learning.

Maybe we can form a STEM advocacy club, Judy! I felt I should give boys an even shake because I had already done two posts on girls and STEM. I get a little bent out of shape about the reigning stereotypes that assign girls to specific roles. We have to make conscious and persistent efforts to include girls in STEM opportunities, and help them believe in themselves. In fact, our STEM workforce will decline in numbers if we don’t pull more women into STEM. So, my focus on boys wasn’t meant to be at the expense of girls. It’s just that these young men aren’t doing well in school and it’s time we implemented a curriculum that actively engages all students in learning in a variety of ways. Thanks so much for your comment!

YES, MaryEllen! I totally agree about the “A” in STEM. In fact, a friend (a musician) and I are doing an eCourse on STEM/STEAM in October through the PLP (Professional Learning Practice) site. I’ll post the link to the course when I get it. Thanks so much for bringing that up. Someone has to add beauty to the world, after all.

Joetta, one of the recommendations for meeting the learning needs of boys is exactly what you point out – the need for male role models and mentors. It was hard for me to relate to the competitive, single-focus, motion-oriented male psyche.

I like to think that as my teaching career progressed, I did understand more about teaching these active young men, however. I had one class of 22 under-achieving, highly disruptive 8th grade boys in 2000 – including some felons. I totally threw away the book on traditional teaching. I called in a college professor who took them around the newly-constructed campus and helped them identify and choose a location for a wetland. They dug out the wetland, chose plants to go into it, built a weir to back up the water, and took responsibility for its success. This was probably their most successful year ever – they loved getting to school. On days when they were building the weir they would show up at 7:00 in the morning with their own tools. Their parents had a way to be involved and showed up with sandwiches, coolers of water, and sometimes to cheer them on. These boys never got into fights or disrupted when they were working on physical tasks of this sort. They were like different people. I’ll always be glad for that.

From another perspective . . . did they know Objective 1.2 for The Test? Not always. Theirs was project-oriented work, not test-oriented work. They were learning about vascular plants rather than icebergs. But they had at least a year that they were successful as students before they hit high school. That has to count for something. (And on another note, their test scores were higher than in previous years. Go figure.)

My concerns with the way STEM is implemented are 1) T and E are only seen as a way to teach S and M. The science and math are taught and then a pile of materials are dropped in front of the students and they are told to build a structure or make a machine. The photo of the catapult in your blog is a good example. Many students would not know to brace the legs as these students did; theirs would fall apart and they would get frustrated. In addition, how real world is it to put pieces of wood together with tape? I’m a coach for BioMoto, a STEM club involving physical fitness and motor sports. One of our challenges was to build a device to move a 5 gallon bottle of water 10 feet. Students had no trouble coming up with a simple design, they said, “build a platform, put wheels on it.” When I asked what materials we would use and how we would form the platform out of the materials and how we would attach the wheels, they fell silent. They knew the science of friction and rolling objects, but they didn’t know the engineering of load bearing or the technology of nails and bolts.

2) My second concern with STEM programs is that there needs to be some preparatory teaching and some summarizing, active boys need to stop and listen during these periods. Playing with sticks, tape, and spoons will be fun, but lessons need a point and that point needs to be stated as some time in the lesson.

Powerful and informative comment, Kurt! And what you say is sadly true for a lot of STEM lessons. There’s at least one practical reason for that – it’s called high-stakes testing. A lot of math and science objectives must be taught – and taught in a particular scope and sequence. Because so much is riding on student test scores, schools often use STEM as a method of reinforcing the those science and math objectives. So STEM (engineering) becomes the application for this knowledge. That’s not the ideal approach, but it’s better than the current silo approach in which the kids can see absolutely no reason for what they learn. (Incidentally, the catapult kids hadn’t had any previous teaching on bracing the legs – at least not any that I’m aware of – but they figured it out when the non-braced catapults fell flat.)

I also like your point about the need to use real materials – not just tape and wooden sticks. Again, reality strikes. Buying real materials for 150 kids per teacher to use (that’s about 8 student teams per class) is prohibitively expensive for most schools. But that is definitely where we need to go. Plus, kids have to be able to do this in as little in 45 minutes – the length of a period in some schools.

So you are definitely on track with the need to make STEM a method of teaching math and science, not just an application of something already learned. And ideally we should use real tools of engineering – not just plastic and paper. (We often explain to kids that they are constructing a prototype – not the real thing – but a model of the real thing to test some aspects of feasibility.)

Your second STEM concern is pretty much addressed in most cases, I think. Kids do get preparatory teaching for projects in my experience. And active boys do have to sit and listen – an easier task if they know why they are learning something, and they know that they will need to apply what they are learning.

Thanks so much for your insightful comments, Kurt, and keep us apprised of what’s going on with BioMoto. I looked it up online and I’m impressed with the program. I plan to reference it in a future blog, in fact. It’s a great partnership! (Readers – type Biomoto into a search engine – I can’t hyperlink it in this response.)

Anne