Students: What We Need from Our Teachers

Barbara Cervone and Kathleen Cushman co-founded What Kids Can Do (WKCD) in 2001. At the time, Cervone was directing the Annenberg Challenge, then the largest private effort to reform public education in U.S. history. Cushman, who wrote and edited the Coalition of Essential Schools journal Horace (a model of education writing, even today), had joined adolescent psychologist Laura Rogers, Ted Sizer, and others to start a developmental middle and high school.

WKCD, Cervone says, began “with a fierce determination to spread a more expansive view of adolescent learning: what adolescents could accomplish when given the opportunities and supports they need and what they could contribute when we take their voices and ideas seriously.”

With youth as collaborators and co-authors, What Kids Can Do has produced more than 15 books that bring student voices to bear on schooling, college access and success, and a multitude of other issues vital to teenagers.

Visit WKCD’s website, How Youth Learn, for more resources.

In this article for MiddleWeb, Cervone, Cushman and Rogers share authentic middle grades voices describing what they need from their teachers today.

Student Voices from the Middle Grades:

Five Ways Teachers Can Help Us Do Our Best

by Barbara Cervone, Kathleen Cushman, and Laura Rogers

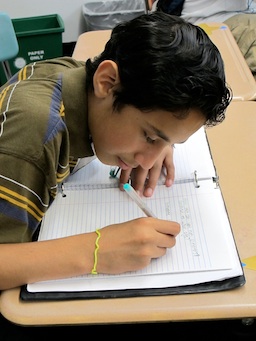

What do students in the middle grades most need from their teachers? For more than a dozen years, WKCD has listened to and gathered answers from middle schoolers nationwide—part of our ongoing commitment to explore teaching and learning from the point of view of students. Here is some of what we have learned and heard. (See the Resources list at the end of this article for more WKCD materials.)

(1) Help us grow into confident learners

How they are doing in school affects middle school students’ sense of themselves. They are newly able to measure themselves through the eyes of others, their peers, and their teachers. They are eager to feel confident, even when they feel out of balance in the rest of their lives. They want their teachers to stick with them, to help them feel successful even when they don’t yet know if they can be.

► “The way the teachers teach, that’s what made me want to act more mature. I can remember my [English] teacher in eighth grade. He stayed on us about doing our essays and stuff. Nobody liked essays, but now it’s my favorite subject, writing an essay. I could write one in about five minutes, because he taught us the formula so many times, really trying to get it across.” —Brian

► “In middle school I had a math teacher and she wouldn’t sugarcoat it for people. She would actually sit you down to look at all your grades, and show you what would happen. She would bring you down to reality, give you the straightforward of what would be the end result. But the way she would speak about it, you wouldn’t be hurt or offended, you’d have a good mindset.” —Geoffery

► “I had a paper graded and they just marked the bad stuff and didn’t point out the good stuff that I wrote. It just made me feel bad about myself. Teachers should say something positive to motivate the student to do better. When they correct papers they always mark the stuff that’s wrong, and just say, ‘Improve on that, fix that.’ They should say some stuff that will help the student feel better about themselves.” —Daniel

► “She was real down-to-earth, really talkative, but she was also very . . . ‘teach-ative’—I don’t know what word. She was very smart. She’d teach you. Like, she’d try with you until you got it, and she was real nice. She’d offer to stay after school, so you could go there if you didn’t get it.” —Kaitlyn

(2) Give us space to figure out who we are

The self-image of kids in the middle grades increasingly derives from their social interactions outside the home—how they present themselves and imagine that others see them, how their classmates interact with them, and how adults treat them. Often they try on different versions of themselves, looking for the fit they want. Many times they draw conclusions that discourage them. For students balancing issues of race, ethnicity, or gender, the drive to assert who they are and who they are not is palpable.

► “I feel dumb, I feel bad inside, because they put the other people in smarter classes. They’re putting them way over there, and they’re smarter than me, but we’re both [learning] the same skills and we’re both getting the same grade. It makes me feel different.” —Tiffany

► “I am not American, I am from a Sinalueñse mother and a Yucateco father that came together no matter the critiques of them. / I am not an alien, although my initials are E.T. / I am not a shoplifter, my Mom pays for everything I buy. / I am not going to be a high school dropout, I am full of potential that sometimes I don’t show for everybody to see. . . .” —Elizabeth

► “I feel invisible.” –Steven

► “I’m gonna be one of those professional women who wears high heels to work.” —Yamille

(3) Understand the ways that grades affect us

As students approach the end of middle school, they may begin to appreciate the ways teachers use grades both to assess their work and to encourage them to do better. Still, many students will experience a teacher’s encouragement as contradicting the grade you assign—and when that happens, they listen to the grade. They are extra sensitive to how they stand compared to other students in their class. At home, grades may matter to students’ parents in ways you never intended.

► “When you get a bad grade and teachers say you’re trying, I think they’re just trying to motivate you to maybe study next time, and try harder to get that A or B that you want.” —Daniel

► “I think the teacher should [give criticism] privately, ’cause kids make fun of you when you don’t do good—they call you dumb and stupid.” —Edward

► “I’m always trying to get A’s, trying to please my mom because I know she has a lot on her mind, and if I get bad grades, then it’s just another problem for her to deal with.” —Genesis

(4) Involve us in conversations about what’s fair

Middle school students often hold a different perspective about what’s fair than their teacher does. They are highly tuned to who gets called on in class. They resent group punishment. They may balk at the notion of shared responsibility. They may be short on the empathy you hope they’d show to classmates. Yet they are ripe to talk about what’s fair or unfair.

► “My teacher will get us interested in a topic and we’ll all be raising our hands and wanting to say something about it. But he only picks on two people to say something. I usually call out, because I’m dying to get to make a comment, and then the teacher’s like, ‘You’re supposed to raise your hand.’ How am I supposed to raise my hand if you’re not picking me at all?” —Genesis

► “Teachers let that favored student do more, even if it’s just like a little thing like moving up in the room, or leaving when you want to. As much as students say, ‘I don’t care,’ they know deep inside that they care.” —Heather

► “They’re trying to say, ‘The whole class has to take the punishment, because we’re all in this together.’ Well, for me it’s not fair.” —Genesis

► “The first week of school, my teacher had us decide on rules for how we’d behave in her class, like being on time, no put downs, having a group mindset. We also talked about what should happen when someone breaks a rule. I liked that my teacher asked our opinions.” —Mario

(5) Encourage us to spread our wings

All too often we reward middle (and high) school students when they toe the line, when they say no to unhealthy risks, when they stick to the answer we’ve taught. We don’t offer enough opportunities for kids to spread their wings, to take positive chances, or to make a substantial social contribution. The curiosity, energy, and flashes of independence that mark early adolescence, when nourished, can yield remarkable results, producing newspaper headlines like these (from WKCD’s daily new bulletin, “Kids on the Wire”):

“Fort Lee Middle Schoolers Design, Refurbish Vietnam and Korean War Memorials”

“Middle School Students, in National Engineering Competition, Design Cities of Tomorrow”

“Eighth Graders Raising Money for Water Well in Nepal”

“Indiana Middle School Students Bring Wii Gaming to Nursing Home”

“Rhode Island Middle School Students Design Video Game to Help Stop Abuse”

“Students Join Scientists in Search of Asthma Triggers”

“Middle School Students Make History by Writing History”

“Kansas Middle Schoolers ‘Sing It Out’ Through Collective Songwriting with Elders”

“Stove Project by Massachusetts Middle School Students Sparks Global Youth Action”

Resources

“This Is My Place”: Middle Schoolers Talk About Social and Emotional Learning (video)

“You Don’t Know Me Until Now”: Latino/a Middle School Voices (photos and PDF)

Making Math Come Alive: Middle Schoolers Talk About Mathematics and Everyday Life (video)

How Do I Grade? An Exercise for Teachers (reflection piece)

What’s Fair from a Student’s Standpoint? An Exercise for Teachers (reflection piece)