How to Close Read the Language of Film

In my introduction to this series on close reading of media texts, I made note of how enamored today’s students are of the media.

While most teachers use media in their classrooms, not many have received adequate training in their colleges of education to understand how close reading applies to “the media.” (Nor has professional development kept up, which is why I include film in my media literacy workshops.)

Since teachers use video and film in the classroom, and because the new Common Core assessments (Smarter Balanced, PARCC) both include video in their testing, I think it’s more important than ever that 21st century students become “critical viewers” and more “film literate.”

When students are challenged to “close read” a video/film, they must not only learn how to deconstruct the “media text,” they must also understand and appreciate all of the elements and techniques that are used to create it.

“Films can be read like texts. Their images should be unpacked just as we would unpack the imagery in a written passage. (Students should) think carefully about how visual or aural tools enact, reshape, change, or critique an author’s textual expressions.” (Holly Blackford, “The Basics of How to Read a Film”)

The languages of the moving images

I define the language of the moving image (video/film) as both the tools and the techniques used to imply or create meaning. Here is my short list of those language elements:

▶ Cameras (cinematography)

▶ Lighting

▶ Audio/ Sound (includes music)

▶ Set design

▶ Post production (editing, special effects)

▶ Actors (wardrobe; makeup; body language; expressions)

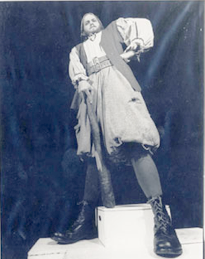

The late film critic Roger Ebert suggested that teachers first consider using film stills (for example, publicity stills) rather than film clips to introduce what he called “frame analysis” (analogous to close reading).

1. Where is the camera positioned?

2. How does it make the giant look?

3. What else might a low angle/upward shot of a person signify?

If you easily answered the first and second questions but were stumped by the third, you’re not alone. As photographers and cinematographers know, when you shoot up at a person, you make them not only appear larger but also more powerful and commanding than they might normally seem.

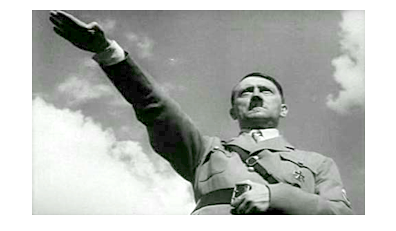

The documentary filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl famously photographed Adolf Hitler from a low angle in the 1935 propaganda film Triumph of the Will.

Representation of character

Filmmakers can use a number of techniques to establish and develop characters. Their choice of camera techniques, acting…editing, lighting and sound all contribute to the representation of a character. – Brett Lamb

Another way that filmmakers communicate to audiences is through the placement of actors within the frame. Consider the farmer, who’s come to make payment to Atticus, at the beginning of To Kill A Mockingbird.

Connecting film analysis & the Common Core

The Common Core makes two specific references to film in the English Language Arts (ELA) teaching standards.

▶ In 7th grade students are challenged to:

Compare and contrast a story, drama, or poem to its audio, filmed, staged, or multimedia version, analyzing the effects of techniques unique to each medium (e.g., lighting, sound, color, or camera focus and angles in a film).

▶ In 8th grade students are challenged to:

Analyze the extent to which a filmed or live production of a story or drama stays faithful to or departs from the text or script, evaluating the choices made by the director or actors.

To assist teachers who want to meet these two standards, I recently created this lesson plan which engages students by having them read a passage from Harper Lee’s novel and compare it to the same scene in the screenplay. Students must also think like a director/cinematographer and decide where and how to position the camera in order to recreate the scene, which takes place just after the jury has found Tom Robinson guilty. Here’s how the director set the scene:

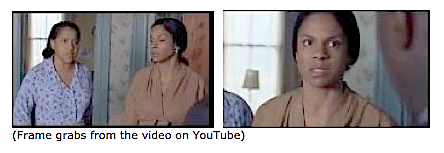

A scene from A Raisin In The Sun: In 2008, a revival of the Lorraine Hansberry family drama A Raisin in The Sun was adapted for television, with rapper-producer-actor Sean Combs in a lead role as the son Walter Younger. (This contemporary version might resonate more with today’s students than the black-and-white version with Sidney Poitier as Walter.)

In a pivotal scene, Walter is preparing to walk out of his mother’s apartment, even though his wife wants to talk to him. An argument ensues. Notice how the director places daughter-in-law Ruth (portrayed by Audra McDonald) in the middle of the frame between mother Lena (portrayed by Phylicia Rashad) and son Walter, representing a key dynamic within the play.

Editing (post production)

When most of us watch film, we’re not really aware of all of the techniques filmmakers use. Post production editing is one of the most powerful, as directors and editors pick and choose which scenes and images will be included in the final creation and how it will all be fitted together. In my workshops, I like to call attention to the editing process and the way it shapes our responses to the film, in hopes teachers will do the same with their students.

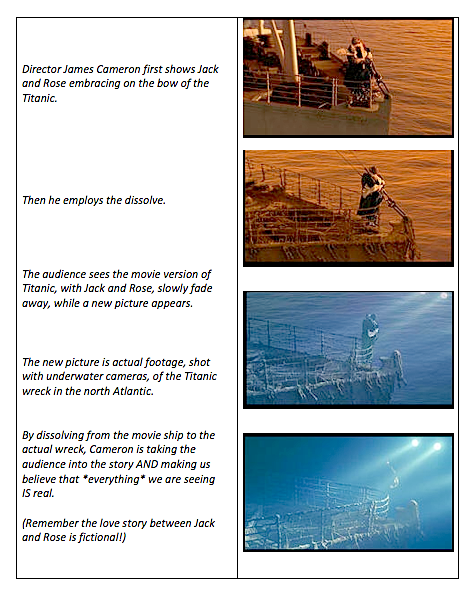

Consider the 1997 film Titanic. Many students believe this to be a true story, but in fact it’s a docudrama, a blend of true and fictional elements. One of the techniques the director, James Cameron, uses to make us think it’s all true is the “dissolve”—when one image slowly fades away while another image begins to replace it, often representing a shift in time or location, or both.

One memorable example of this technique: We meet the older Rose at the beginning of Titanic and as she reminisces, the dissolve begins and we move from the present to her past – her memories come alive. Clever directors can also use the dissolve technique to add a sense of reality or truth to their fictions. Consider this example:

More resources to explore the language of film

There are many more ways that filmmakers communicate. I recently created this Language of Film web site to assist educators. It includes links to articles, lesson plans and resources. And be sure to visit the Film in the Classroom index page at the New York Times Learning Network to find links to their large collection of articles and resources for teachers and students.

ALSO: My colleague Heidi Hayes Jacobs and I recently unveiled this Film Canon website. We invite educators who already use film to join (it’s free) and contribute to the growing list of films appropriate for the classroom. You’ll find recommendations and related materials organized by grade levels (e.g., middle school).

In a recent edition of his book The English Teacher’s Companion, author-educator Jim Burke urged teachers to embrace movies, advertising and other visual media and to find opportunities to use them in instruction. Otherwise, he says, teachers risk their credibility with students.

That’s some good food for thought. I hope my four-part look at the close reading of media texts, here at MiddleWeb, feeds your appetite for including media literacy in your approach to close reading and the Common Core.

Also see the other articles in this series:

Part 1: Close Reading and What It Means for Media Literacy

Part 2: Close Reading: Visual Literacy through Photography

Part 3: Close Reading of Advertising Promotes Critical Thinking

_____

Frank W. Baker is a media literacy education consultant and the author of three books, including Media Literacy In the K-12 Classroom (ISTE, 2012). He contributed two chapters to Mastering Media Literacy (Solution Tree, 2014). In November 2013, Frank was a co-recipient of the National Telemedia Council‘s annual Jessie McCanse Award given for individual contributions to the field of media literacy. Follow him on Twitter @fbaker and visit his website.

I am a k-9 licensed educator with a film BA and a MA in teaching. Thank you for the article! It’s good to see how my former training can relate to the common core.

Hi,

The article that I read puts the insights into documentary videos. These videos and films are provided in this section for you to learn more about the history of racism.