3 Perspectives Improve Peer-to-Peer Response

This summer I have piles of books around me (which is rather beautiful) and email notices coming from my local library every day telling me to come pick up the books I’ve requested (novels and teaching resources).

I am also listening to books when I run in the mornings and when I drive to and from summer school. I am reading books before school, after school, and before bed trying to find great books to share with seventh graders. And in between all of this, I am reading blogs that recommend more books.

As a reader, I tend to respond to texts from three perspectives.

- First, I am responding in a sort of visceral way — less relating to intellect and more of a deep inward feeling. Does the text resonate with my being, my humanity?

- I also read to learn and want the text to make me think about something in a new way or teach me something about myself, the subject, and the world.

- Finally, I respond as a writer. When reading teacher books, I like stories, but I also like the suggestions to be clear, organized, and easy to follow. When I read literature, I appreciate fresh phrasing, an unexpected metaphor, meaningful flashbacks, and character revelations that resist didacticsm.

I think readers naturally respond to texts from different perspectives. Depending on their purpose for reading, some perspectives might be stronger than others, but I respond to texts as a human being, as a reader, and as a writer.

Thinking about teacher responses to student work

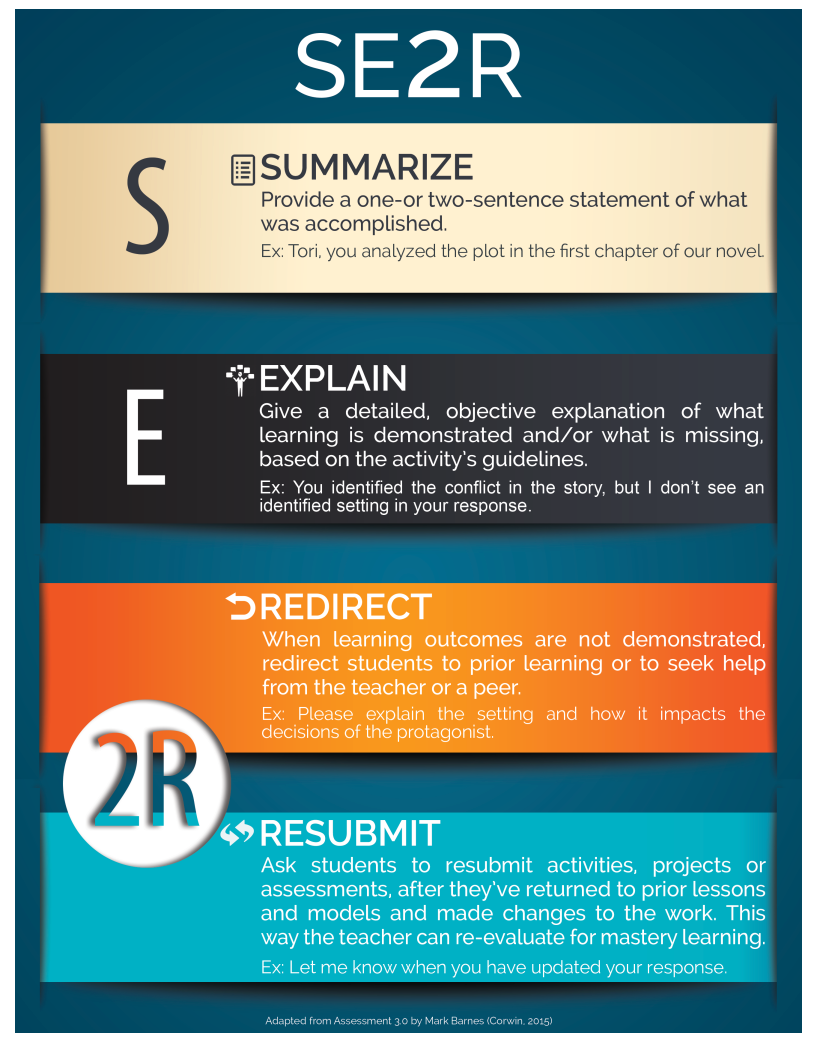

As an ELA teacher, I think a lot about how I respond to students’ work. I am moving toward a no grades classroom, so the responding, the feedback, is the only assessment form I plan to use next year. Mark Barnes suggests the formula of SE2R: summarize, explain, redirect, resubmit. This is really helpful for teachers because when we are reading student work, we also respond as teachers.

While I still respond as a human being, reader, and writer, there is this added responsibility to redirect or move the student toward some deeper thinking or new technique. Unlike my reader response when I am alone, in the classroom, my responses have the power to move minds and hearts.

What I say or write has the potential to ignite inquiry or silence a thread of thought. I have found that if I hold on to the human being part of the response (which I tend to skip over when life gets hectic), more learning happens.

Getting students to respond to peers

This is nothing new. Teachers do this everyday, and I know just how challenging it can be to teach students to talk to each other about their reading in meaningful ways (especially when they have been “programmed” to sit quietly, raise their hands to speak, and defer to the teacher’s authority). I just want to share one approach that has worked well in my middle school classroom (but also in undergrad and grad classes I’ve taught).

A triple approach to reading response

The three-perspective reading response approach has been a helpful resource for me and for students when responding to peers’ writing (e.g., informative essays, arguments, fiction, personal narratives, poetry) and reading blogs (text comparisons, reviews). I include sentence stems, some of which students wrote, but most I crafted myself because I have an agenda.

Here is the frame of my three-perspective approach:

1. Respond as a human being: How does this text affect you emotionally or personally? What connections can you make to the topic personally in your life or in the life you hope to have?

- “Your essay/poem/critique resonated or spoke to me personally because_______.”

- “I appreciate you writing on this topic because in my life________.”

- “This topic/idea hits me in the heart because I really care about_______.”

2. Respond like a reader: What did you learn? What will you do with this information? How have your beliefs or thinking on this shifted because you’ve read this essay?

- “I understand you better as a person because you’ve shared this story about ______”

- “I am grateful that you’ve trusted us with this experience about _______.”

- “I never knew about this” or “I will try your suggestion because __________”

- “This is a fresh perspective on ____ because usually people talk about it like______”

- “I understand the text/character/conflict/plot better now because before I thought_____and now ____” or “I missed that part about ____when I read______”

3. Respond as a writer: Which line or phrase seemed most vivid or funny or descriptive or unexpected but good?

- “The line that seemed most powerful/insightful in my view was _________________ because _______.

- “The features of this genre that you did well were______________. For example, __________”

- “One technique I noticed was________; for example, ______________.”

- “Something unique (fresh or surprising) that you did was __________________.”

- “The best example you gave was _______________________”

Here are a two student examples:

► Hi, thanks for sharing this poem about Love. I read the poem, and I agree with your interpretation of your poem because even though I haven’t been in a relationship most of my friends have.

► I appreciate you writing on this topic because in my art class we were learning About this and this gave me more information on different pencils you can use to draw something. The line that seemed most interesting was when you said “The H stands for hard” because my sister uses these pencils but I never knew what the H and B meant. But anyway I really enjoyed learning something new.

Some students do not use sentence stems after doing this a few times. Few need the words once they get that their writing moves others to respond. The words come because they experience and like how it feels to give and receive this kind of feedback from each other. And I think this is “good.”

How do you facilitate peer response in your classrooms? I hope you’ll share your thoughts in the comments.

Sarah J. Donovan (@MrsSJDonovan) is junior high ELA teacher at Winston Campus Junior High in Palatine, Illinois. She earned a PhD in English from the University of Illinois at Chicago, specializing in young adult genocide literature and the ethics of teaching. She is an adjunct professor at DePaul University and Dominican University where she teaches graduate courses in adolescent development and teaching in diverse classrooms. She is currently working on three projects with her seventh graders: a No-Grades Classroom, Bearing Witness: Documenting the Stories of Our Community, and the Inclusive Literature Workshop. Follow her at her collaborative website, Ethical ELA, on Twitter, and on Facebook.