Exciting Middle Graders about Research Papers

A MiddleWeb Blog

“Do you always do this research project?” she asked, as class was ending.

“Do you always do this research project?” she asked, as class was ending.

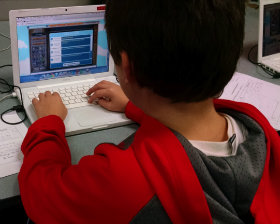

All around her, classmates were putting away laptop computers. She had spent the past 30 minutes writing with intensity and passion. She had not wanted to stop writing even when I asked her multiple times. She was constantly showing classmates what she was discovering, teaching them.

“I really like it,” she added.

“Some years, we do political essays,” I responded. “Particularly when it is a presidential election year, like this year.” She gave me a look like she was sucking on a lemon and shook her head at me, as if to say, that is soooo boring.

Then, as a typical sixth grader, she said it anyway. “That sounds soooo boring. This is way better. I got to pick my own topic, learn more about it, and write about it,” she said, and as she walked away to her next class, she added: “You should do this every year, Mr. H.”

I wish every conversation with my sixth grade students about classroom research projects were this positive. Just as it is not easy to find the perfect ways as a teacher to engage young writers in the intricacies of research-based essay writing, it’s not so easy for them as writers to crack the code of this genre of composition, never mind be excited about it.

A memory that gives me shivers

Kevin, behind his 6th grade teacher

I still remember a monumental, and nearly insurmountable, research project that I was assigned in elementary school on an African country. It caused no end of frustration at the time and the memory of it still gives me shivers.

I don’t even remember the country I researched nor do I recall what I discovered in my inquiry. I just remember not enjoying it, not at all, and I loved writing even then. I know now that I don’t want to be that teacher. I know that I don’t want my students to be that kind of researcher.

In the past few years, as the Common Core has pushed us all much deeper into research and expository/informational writing, I’ve been trying to keep reminding myself of some of the lessons I learned, and continue to re-learn through re-reading, from Christopher Lehman’s great resource on classroom projects: Energize Research Reading & Writing.

Lehman reminds us that small scale research endeavors are more effective than huge research projects that overwhelm students. He suggests a simplified note-taking system, and he urges teachers to allow students to have choice in the matter of topics, within a larger frame.

I’ve taken this advice to heart.

Creating more opportunities for student choice

This year, I found great success with my students’ ability to generate a topic of interest:

► I tapped into a new tool in Google Docs for gathering information;

► shortened the writing expectations to focus on structural development of essay;

► reinforced paraphrasing and quoting while arguing against the plagiarism of copy/paste; and

► added in “extension activities” that allow students to move beyond the essay itself to show understanding with media projects.

The result was a satisfying few weeks of research-based writing, and even my struggling writers made significant progress in writing longer pieces, not to mention learned how to effectively use the Internet for research (done in conjunction with lessons coordinated with our school librarian). The various extension activities have also provided my top-tier writers with an means to push themselves at every step of the way, meeting their needs, too.

I did provide a list of possible topics for those students who struggle with this part of the writing. In the end, the topics ranged from Hybrid Cars to Nuclear Power to Genetically Modified Foods to Air/Water Pollution to Endangered Animals.

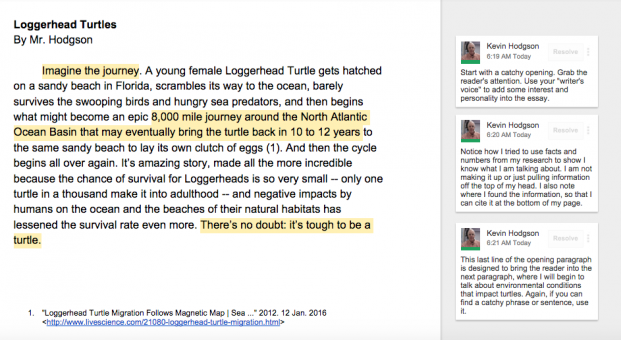

As teacher, I also was writing my own essay a day or two in front of them (my topic was Loggerhead Turtles, which connected to the novel, Flush, that two classes were in the midst of reading, so my essay had two functions: make visible my writing process and give them information about Loggerhead Turtles).

I annotated my draft files, printed them out to share with students, found and corrected mistakes, and talked through what I was doing, both my struggles and my success. I hoped that by sharing my thinking, it would make more visible the writing process, and for many students, it was helpful to watch their teacher writing research with them.

Many students kept my annotated essay files in front of them as they worked (although more than a few copied my writing style in the opening paragraph.)

Walking through one student’s research

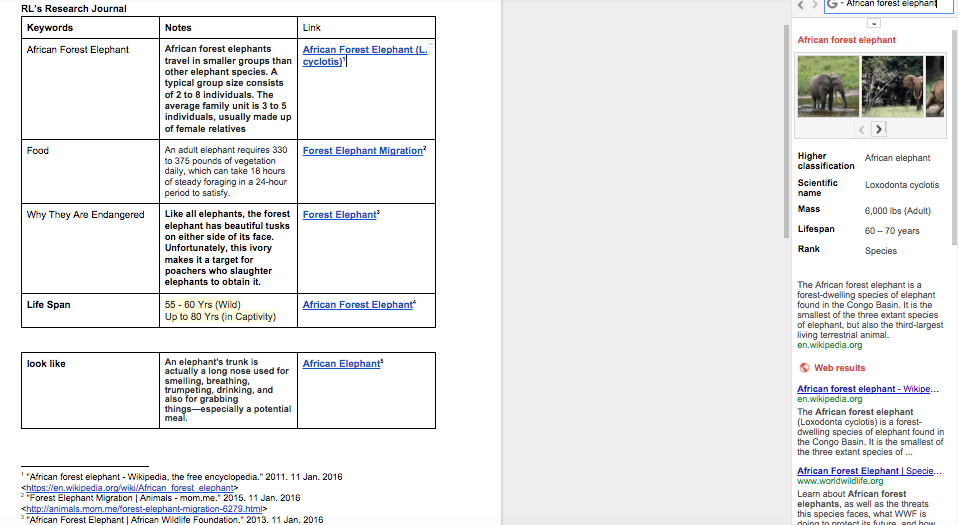

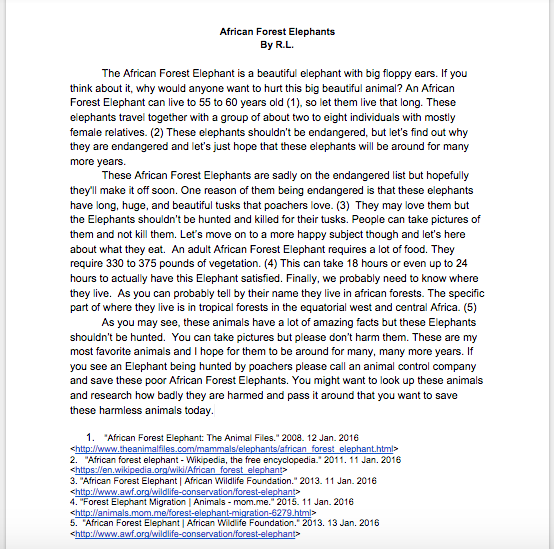

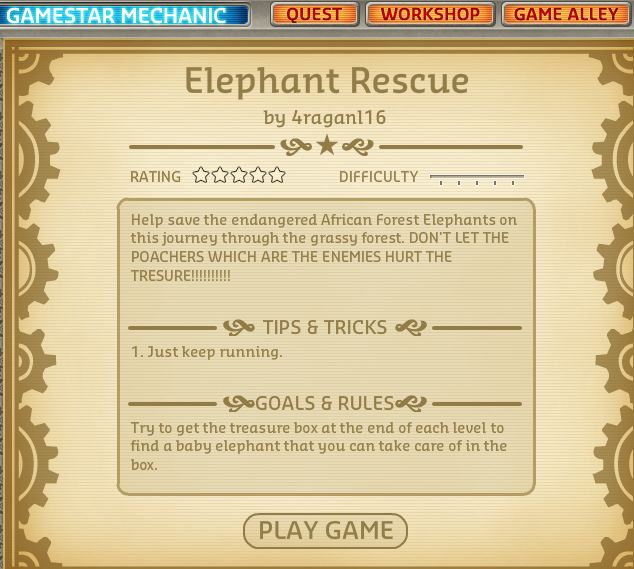

One particular student, whose work I want to share here as an example of our process, was interested in the elephant generally, and then they narrowed down the focus to the African Forest Elephant. This important “narrowing” came after our consultations and the realization that “elephant” as a topic was too broad to cover in a small essay.

In Google Docs, this student tapped into a relatively new built-in tool called Research. This allows writers to do searches and citations right in a Google Doc. I had all students set up a Research Document where they would take notes and grab information, while also keeping track of websites and citations. This is a separate document from the essay itself. By doing this, I was able to have a handle on how students were faring and who needed the most one-on-one assistance from me during class.

After gathering information, I did an extensive lesson around plagiarism, quoting and paraphrasing. I acknowledged the ease of which we can now copy and paste text from one source into another with technology, but I emphasized the need for a writer’s own understanding, words and voice to come through, and that if you use information from research, you need to point to it with citations.

We used a very simple citation method, connecting the bibliography resources with a number in the text itself. The essay had to be at least 300 words long, cite two sources and develop from an introduction into a body of research and end with a closing.

All students had to create a “media companion” piece to their essay, as well, using Google Slides to bring images, maps, graphs and other items into their understanding of the topic that they chose to research.

At this point in the year, they are adept at Slides, so this is mostly independent work. This companion piece allows them to “tell the story” in a different way than an essay, and we talk about how media can inform a reader on a topic.

Finally, for students who finished the essay and the media piece and wanted to do more, the extension challenge was to create a video game project in Gamestar Mechanic, using the topic of their research for the basis of their game. This provided another connection to the research, and tapped into their skills developed earlier this year around video game design.

A few thoughts

The various threads of this unit – research, formal essay writing, media piece, game design – come together to provide students with a larger understanding of not just the writing process, but also a deeper connection to and understanding of the topic they chose to research.

If the unit was successful, they will remember not just what they did, but what they uncovered. And hopefully, those writing and research skills will translate into deeper analysis and writing in other subject areas this year and beyond.