Get Students Working Effectively in Groups

By Barbara Blackburn

By Barbara Blackburn

Group work is one of the most effective ways to help students learn. It can increase student motivation and is an important life skill.

When I was teaching, some of my students didn’t like to work in groups. They complained every day until I brought in a newspaper article that said the number one reason people were fired from their jobs was that they couldn’t get along with their coworkers. That was an eye-opener for my students.

Several years ago, I was in a classroom in which the teacher bragged to me that her students worked in groups all the time. When I asked her students, they told me that the desks are placed in groups, but they just read the book silently and answer questions individually. After thinking for a minute, one student said, “We can ask each other for help if we need to.”

That’s not really group work. Effective group activities provide opportunities for your students to work together, either with a partner, a small group, or the entire class, to accomplish a task. In these instances, everyone has a specific role, and there are clear individual and shared responsibilities.

Structures for Effective Group Work

Shannon Knowles explains that in a setting such as a science lab, “I try not to change groups. My kids realized if they complained about other group members, I’d change the groups, so now I explain as they get older, in the real world, you have to work with someone you don’t like, so I don’t change as often now.”

However, I also think students should work with a variety of people, and they should not be limited to working with the same students all the time. In my classroom, I used groups of four for some activities and pairs for other activities. I switched my students around often enough that they rarely complained about other group members. They knew that I expected them to learn to work with everyone and that they would be grouped with someone else later.

Selection of Group Members

Next, decide how the groups will be formed. Will students be allowed to choose their groups? In my classroom, I allowed students to self-select their groups on rare occasions. Most of the time, I assigned groups in order to manage bullying and negative peer influences.

This is up to you, as you know your students. There are times you will want to assign groups based on skill levels or interests; just be sure you don’t label students by always assigning them to certain groups.

Roles for Group Members

A critical step is structuring your group activity. Create an activity that requires each student to contribute to the task. It’s important to assign roles for your students, although you may want students within a group to choose their roles.

Sample Roles and Responsibilities

Facilitator—Leader of the group; facilitates action

Recorder—Records comments and/or work

Reporter—Reports on progress to the entire group

Timekeeper—Keeps the group working within time limits

Technology Manager—Coordinates technology use

Encourager—Encourages others

Summarizer—Summarizes work and may report to the entire class

Fact checker—Checks work from group; researches facts

Reflector—reflects on comments from group, asks probing questions

Designer—Designs the project

Creator—Creates or builds the design

I encourage you to rotate the roles within the team for different assignments so that one or two students do not dominate the group activities. You should also take time to teach students about their roles and responsibilities. As Duke University basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski reminds us, it takes time and intentionality to transform a set of individuals into an effective team.

Rules for Group Work

I found that I needed to discuss my expectations for the noise level of the classroom. I wanted my students to talk to each other. But they needed to talk to their group members, not the entire class.

You might come up with a catchy way to describe an appropriate noise level, such as “Bees Buzz.” Bees buzz when they are being productive (making honey), but they don’t shout. I was in another classroom in which the teacher talked about using your “12-inch voice.” Her students knew that meant that people within a foot (within the group) should be able hear you, but not those outside the group.

I also used a rule called “ask three before me.” This one works when your students are in groups of four. It simply means that a student should ask his or her group members for help before asking the teacher. This encourages students to look to each other for support instead of always looking to the teacher first.

It’s up to you to decide what rules you need in your classroom. Be sure that your students understand your expectations, and monitor the groups continuously to ensure that all students have an opportunity to participate.

Effective Groups Strategies

In addition to traditional pair-shares or small group discussions, you may want to try some different techniques. Here are three that many teachers, including myself, have used successfully.

Jigsaw

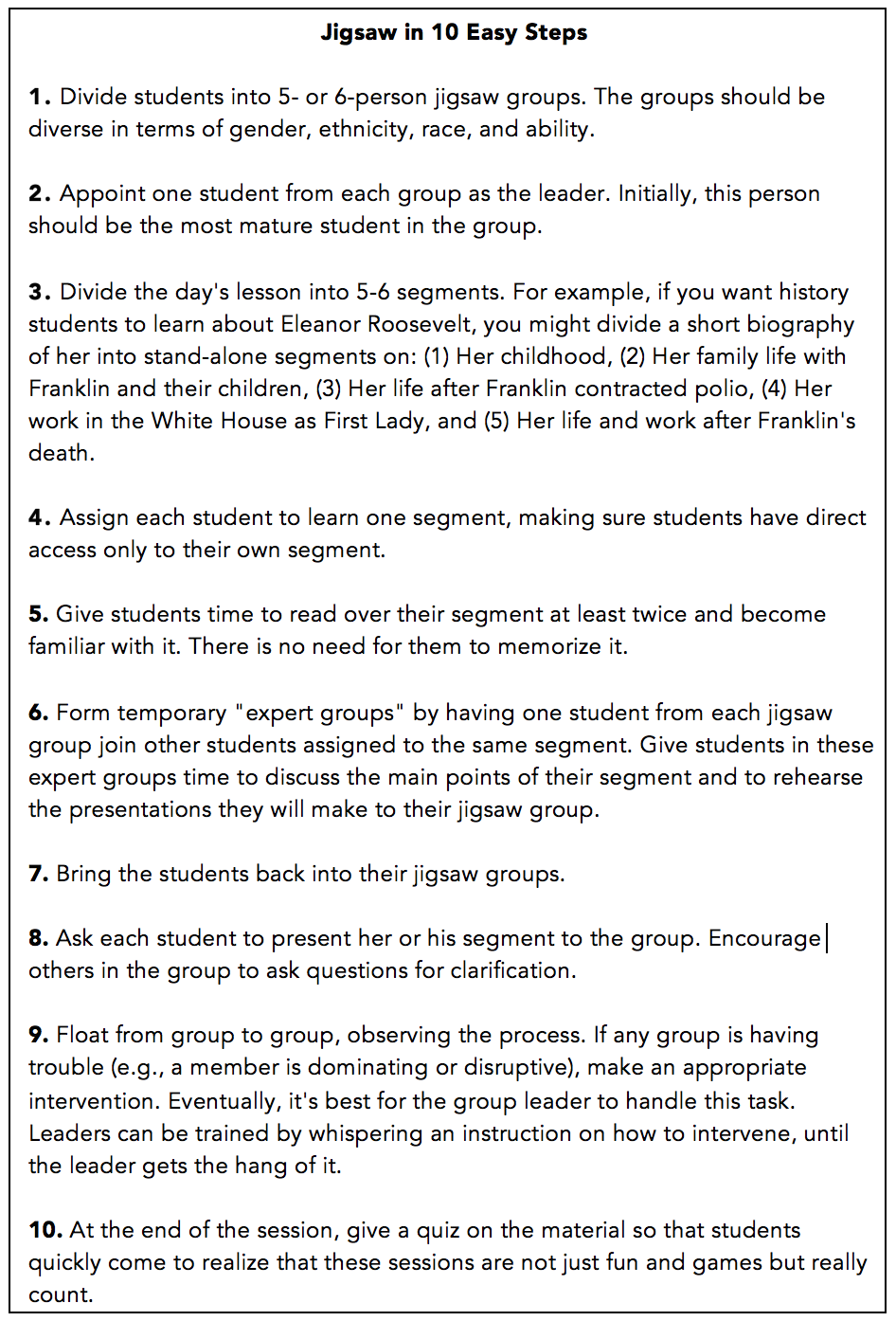

One method I used was jigsaw, in which students are placed in small groups, assigned a topic, move with other students assigned the same topic, research the information, then return to their original group as an expert to teach the material. Instead of me lecturing the whole time, students taught the material. In addition to being more engaging, students took ownership for their learning.

Traveling Heads Together

An adaptation of the jigsaw method, here each student is placed in a group of six, then is given a number, one through six. After the teacher gives the task, all of the number threes move together, etc. Numbered groups complete their task or part of the assignment, then move back to their home groups, just as in the jigsaw method. However, instead of simply presenting information, they must also explain the processes used to develop their information.

Circle of Writers

Elements of Group Success

These group projects are effective when teachers create meaningful activities, design structures that ensure individual and group success, provide instruction to support the process, and make learning fun. And students will respond in a positive way!

I teach 6th grade humanities and often use group projects as a learning tool, not only for curriculum but also for life skills. I tell my students that I am looking for not just the finished product, but also how you got there. Collaboration is an important part of my curriculum, and I ask for feedback from the participants to see how the groups have done. It is done confidentially and gives me some good insight as to who did what on the project, who worked well with others, and how they overcame any difficulties.

I agree students should work in groups because they will learn more.

Thank you so much! We are encouraged to use groups but this helped me understand how to overcome group dynamics of the dominating “do it myself” student and the sit back and let them student.

Good clear advice on building group dynamics. I have been incorporating group work into my classroom for the last 2 years, but I have struggled. I have too many students willing to take a free ride during the group learning time. I think that some of these strategies will help me next year to really teach my students how to work together and everyone pull his own weight.

I’m glad you found them helpful!

Thank you for that. We are actually doing group research in my class; your website was very helpful!!! Thank you for all your help, Dr. Blackburn!