How I Finally Figured Out Collaborative Writing

I want to share some of what I’ve learned this year about having students work collaboratively on writing assignments (and how I graded them). But first I need to say this:

When it comes to how we approach students’ learning, I’d like to suggest that the world of school is absolutely archaic compared to the “real world” of our students.

It all fell into place for me when my son and husband were playing Super Mario Brothers on the Wii.

To us, that is just how games work, but he wanted to know:

Why go all the way back to the beginning and re-do the part you already know? Why not go online, find someone who knows how to skip that level, and learn how?

This small moment has given me insight into this generation’s learning process in a way that nothing else has. He had nailed the paradigm shift in teaching that I previously couldn’t put my finger on.

Today’s students need to know how to find and obtain answers that keep them moving forward because they live in a world where information is not the currency, but the ability to use information is.

Knowing what to know

I think we can all agree that in the real world there are few instances where we are not allowed to ask for help or seek out experts – few situations where we absolutely must struggle alone and hope that we’ll suddenly understand. Yet this happens in most schools every day.

Meanwhile, in 21st century workplaces industry and business people complain when an employee doesn’t know how to solve problems with a team. The ability to memorize and “know your stuff” (including a lot of stuff you don’t need to know) isn’t nearly as important as it once was.

In The Washington Post’s January 2015 article, “Why are so many college students failing to gain job skills before graduation?”, reporter Jeffery J. Selingo shares part of an important conversation with prominent thought leader John Leutner, head of global learning at Xerox.

“People know how to take a course. But they need to learn how to learn,” Leutner told him. The reason so many new workers take time management courses, he said, is that while they were in college someone else set their priorities for them. “College graduates now move into a contextual job, not a task-based job.”

In my son’s case, he knew that the information was out there (in the form of tips or online tutorials), and he wanted to use it as his own without having to experience the multiple trial and error moments that people of my generation refer to as “the learning curve.”

This is not to say that students don’t have to have perseverance and stamina (along with research skills). But we need to teach them (and sometimes let them teach us) when to exert that stamina, ultimately finding their own best way to solve a problem.

That said, it’s also crucial that we don’t push an agenda that makes all knowledge equal. We must make sure our students know what they need to find out for themselves and what they can relegate to Siri.

The pathway to non-compliance

How often do we reward students for the “right” answer? When do we encourage them to seek information, nuance and understanding beyond what we’ve given them to memorize and regurgitate?

How do we motivate students to be their own best selves, even when the teacher isn’t grading the work or looking over their shoulder?

How do we make writing collaborative?

I set out this year to allow a more collaborative approach in an area where I was least comfortable loosening my teacher’s grip: writing. I’ve always been about the group projects, team presentations, and activities that promoted collaboration. However, for whatever reason, I’ve always held back from allowing students to work together on their writing.

Perhaps it’s because the writer in me couldn’t fathom bringing my thoughts together, on paper, with another person. Or, a more honest answer might be that I didn’t really know what “collaborative writing” should look like. How do you grade something that multiple people have worked on?

I asked the people who know best, my students, what they thought. If I were to allow them to collaborate on their essay for the novel we were completing, how would I know who did what part of the work? What kind of grading could I do?

Guess what. They had the answers even before I’d finished rambling about how I wasn’t sure it could work.

What the students explained to me

What the students explained to me

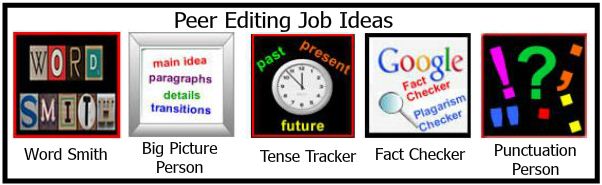

“Well, we could do the whole thing as a Google Doc. Each of us could chose a different color ink, so you’d know who did what part,” Amanda explained.

“And,” Dan added, “all we really have to do to see the whole editing process is to write our suggestions in the comments. Then, we’d share you on it to grade.”

“Ok,” I said, “but how do I grade it? What if there is a student who has horrible grammar on his part? Do I dock the whole group points?”

“I think everyone is responsible for the whole thing. You’ll see in the comments if I told someone that they had mistakes. You’ll be able to trace what happened. If someone doesn’t make the corrections, that’s on him. But, I think everyone will listen to their Resource Group,” Megan said, reasonably.

I took a deep breath and jumped in

So I gave it a try, and it was the best writing we had all year. My students were working diligently, having side conversations about each other’s writing. (Mostly. They are still teenagers).

One thing is for sure, if I had asked them to print their papers and then given them each a colored pencil to edit his or her partner, this would not be nearly as effective.

One thing I noticed right away is that they wanted to continue to make progress and keep writing/typing their paper while someone else was looking it over and commenting – reminding me of Oliver’s admonition that he could just learn as he went along. Talk about a 21st century skill.

And this communal attitude toward writing is practical. Just today, I collaborated with two 8th grade ELA teachers in the creation of a rubric. We then shared our department chair and principal on the document. Every single person had something to contribute, and the final draft was better for it.

So what about the grading, you ask?

You might imagine that grading was difficult, but I did not receive a single complaint when I graded the group as a whole and then assigned another separate grade for their individual contributions.

I learned a lot from this first experience, and I plan to continue to expand the collaborative aspect of writing because it really is the expectation of 21st century workplaces that new employees will be able to work both collaboratively and individually, while problem solving and taking risks.

Just as Oliver wants to forge ahead, relying on the collective knowledge of gamers to help propel him forward through the whole Super Mario universe, I’m hoping to see collaborators work together, learn together, and create together – an approach that will increase student engagement, understanding, and quality of work.

I’d love to hear what you’re experiencing as you try to get serious about collaborative student work . . .please share in the comments!

Feature image: Flickr Creative Commons

____________

wow–this is such a refreshing, modern and innovative article. Truly a resourceful idea, Amber.

Thanks! Innovation can feel messy, so I appreciate the compliment.

Great post … I’ve been doing collaborative writing and I am still figuring it out. Check out my post where things went awry with collaboration: http://dogtrax.edublogs.org/2016/05/06/collaboration-and-chaos-the-best-laid-plans-sometimes-fall-apart/ We’re in a moment where we need to try new things and find ways for our students to engage in literacy practices that translate into their own lives and transform the possibilities of their futures. Your journey is likely one that many of us can relate to. Thanks for sharing your ideas, concerns and aha moments.

Kevin

@dogtrax Hi Kevin. I’m in awe of the future–I can’t keep up with it, so I have to enlist the students and my own kiddos. It is a great time to be a teacher. I also shared your blog-it is awesome.

Another excellent post, Amber. We’re currently GoogleDoc-ing it for our final product of the year and the kids are pretty savvy when it comes to leaving feedback and using it (after a few gentle reminders that clicking “Resolve” doesn’t make a problem go away!). The grading dilemma is a non-issue as the product descriptor makes it pretty clear what is expected and how to get there – and it builds stake.

I usually bust on my son who is quick to hit the YouTube hacks for his video games (I still call them cheats!), but I like the way you re-framed it. Why start over when it’s the Boss Battle you need to re-do (or the wonky transitional phrases, or flat conclusion, or…)? Kids can be great teachers sometimes!

Chris– My husband and I completely think our son’s approach is cheating, but I’ve come to see that is because I am just a child of the 80’s.

Yes, feedback is great w/docs. Honestly, they act like it is texting, and they are more engaged!

Thanks for the thoughtful comments. It is always nice to know people are thinking about what you blog.

What a timely post! Thank you for sharing. I just had a conversation with a parent of one of our middle school students about a lack of communication skills and being able to present to groups. I think this idea would certainly aid in honing those skills. I have been using Google Docs to have students share individual writing with me so I can then give them suggestions and feedback for the revising process. This takes that even further and gives them the opportunity to collaborate on something and work with each other to make the group writing the best. I like the idea of evaluating it both on an individual and group level; that just “keeps the writers honest” in their participation and contributions for the project. We are getting ready to refocus our curriculum and move to a “one-to-one” computer program in another year. I see all kinds of possibilities. Thanks again!

So glad I could help! It is new to me as well, but like you, I see this being a part of our students’ futures in ways we can’t yet imagine. Give it a try and keep us posted!

You mentioned in the grading section that you want to look for quantity and quality. I understand how you would grade the quality of work, but what about the quantity? How do you ensure that each student is putting in the same amount of work? Would it be ok if one student did all the research and writing while another did all the editing?

Great questions! And, not coincidentally, the same ones I struggled with. I try to run a differentiated classroom, so the short answer is that different kiddos will need different quantities. The basic tenet is that unless I’m targeting that skill (say writing), either student could do it. To see how much imput the other students had, I can

look at the revision history

in Google docs and see each child’s contributions. I also have them do reflections in mini-groups, and they are held accountable by their groups. Also, they receive a test grade each quarter based on their participation. I circulate, take notes, and give feedback about the quality of their input in projects, always trying to help them grow, knowing it will be at different paces.

I love it! You really got me thinking. Thanks for joining in.

I love this track you’re on. I went the same route this year, and really I couldn’t believe how effective it was for students to collaborate on writing. Consider not grading the final product at all. Give the students narrative feedback, give them an opportunity to make corrections based on your feedback, and when they have made corrections based on your feedback, publish the work in a meaningful way. Then celebrate the accomplishments of publishing work. That’s it. If grading is a must, conference with the students to ask them what grade they feel they deserve. Ask probing questions and trust that they will be honest and reflective and gives themselves a fair grade.

It’s funny you should mention not grading…I’ve had them assess themselves and found that they pretty much know where they are and what they could have improved upon. In the class participation rubric I mentioned before, I conferenced with them before I gave them my grade–they were spot on. If we disagreed, I’d ask them to think about it and meet again. I’d change grades if something compelling came up, but it was really inspiring to see they can think metacognitively if given the space.

Thanks for the validation! One of the reasons I write is to open up great conversations like this!

Students in my class just asked me yesterday to consider letting them write their final opinion essay with a partner. I told them I would think about it. Last evening I saw your article.

Done! You’re ideas are timely and helpful. I can’t wait to tell my class.

Terry–That’s awesome! It sometimes takes a little nudge to get things going like that. Anything that is experimental is kind of like, “Ok, here we go!” Good luck with it. Please let me know how it goes. You can email me at AmberRainChandler.com.

As “refreshing, modern and innovative” as this may seem, there are some key factors that educators are failing to consider.

It’s stated that information is not the currency but the ability to use information is” and that students are traditionally taught “a lot of stuff [they] don’t need to know.” However, you can never have too much knowledge, and it takes knowledge to know how to use information. In addition, one isn’t truly literate unless one is culturally literate. This also requires knowledge.

This notion that students’ education can be narrowly focused is a big mistake.

It’s also stated that “information doesn’t have to be memorized” because it’s so “easy to locate.” Thus, “the real skill is knowing where to find the best, right answer.”

This presents two major issues: 1) reliance on quick Google searches means portions of the brain are no longer being used. Studies have already shown this is becoming a problem. The brain is a muscle that dies from lack of use…atrophies…just like any other muscle in the body; 2) students won’t be able to determine what is the “best, right answer” if they haven’t retained any knowledge. It takes knowledge…and plenty of it….to know the difference between merely adequate and on point.

It’s stated that students need to know what they should “find out for themselves” and “what they can relegate to Siri.” First, the minute they start relegating anything to Siri is the beginning of lazy minds. Second, in finding out for themselves, aren’t they going to be using tools like Siri? Therefore, the two concepts are not separate and distinct but, essentially, one in the same. Instead of using their own minds, they’ll be relying on a source that isn’t always right.

Thanks for reading and responding so thoughtfully to my piece. I’m going to try to explain what I meant by some statements, as I certainly see what you mean.

The idea of memorizing “stuff” is directly from my own experiences. Though I recognize the value of knowing all the state capitals, I’m suggesting understanding what the function of a state capital actually is, or why historically it was important, is far more important. I know that many students are drilled on information, rather than the broader picture.

I agree wholeheartedly that parts of the brain are not being used, but my perspective offers opportunities to explore social-emotional learning and see benefits, particularly for students who find memorizing difficult and ineffective. At least in my experience, when students are socially/emotionally connected to content, it sticks.

I’ll be the first to say that we, as educators, are in muddy waters when we begin to utilize technology–in part because it changes so quickly. I don’t necessarily believe it leads to lazy minds; I encourage students to pursue all the questions that pop into their heads using Siri or other technology. I find that this expands their knowledge base, rather than shrinks it.

Ultimately, your comments are essential in this conversation. We need to have great dialog like this in order to grow, as I think we must. You’ve given me food for thought, and for that, I’m appreciative.

My co-teacher and I will be doing more station teaching this year. I think this approach will work beautifully for the students. I loved this article!

Thanks! I’m glad it was helpful. Please let me know how it goes. I’m always looking for teacher feedback.

Amber, you dared to do something different here and I love the idea. I see this working with a partnership really well, but what would you suggest? What levels of learners do you believe work best with each other? I will be teaching a very low grade 7 class this year and wonder about pairing students who are below grade level with at level, of at level with above? It seems students who are gifted struggle when working with students who are below grade level and the lower level learner doesn’t participate much in the process…having said that, there’s student dynamics and personalities you don’t want to bring together as well sometimes. Curious on anyone’s thoughts here?

Students still need to be able to produce a complete, coherent piece of writing on their own — this approach allows them to have someone else take up the slack so they can avoid the real work. Once they’ve established a solid foundation as writers, then they should move to this model for some (but certainly not all) projects.

I agree! My students write lots of different pieces on their own. If all students are invested–which happens when they have interdependence and respect for each other–it isn’t taking up “slack,” but instead being able to accept constructive criticism and learn from each other. They write individually often, and I think a mix is appropriate for sure.

I simply loved the article. I have allowed students to write collaboratively for several years. In the past two years, I have also begun allowing them to use Google Docs and that was suggested by a student as well. I found the students peer edit with a keener eye than I do at times. Also, they help me identify trends in their peers’ papers.