An Activity to Help Kids Learn Civil Discourse

I have learned a major truth in nearly five years of retirement, “Once a middle level educator, always a middle level educator.” I may read a provocative article and think, How would my students have reacted. Or I may hear a song on the radio and think, I would have used this to begin a discussion about so-and-so.

And it’s happened yet again following this presidential election. My brain seems to be front and center on the following question: If adults have had a difficult time dealing with one another from the primaries to this post-election period, what are adolescents making of the whole thing?

Middle schoolers are notorious sponges. This year they’ve been exposed not only to social media and televised vitriol but often to angry, divisive rhetoric in their very own households.

They have seen friends and relatives in heated arguments as well as “defriendings” on Facebook, and may even see evidence of bullying fired up by inflammatory campaign talk.

Educators know that adolescents tend to react with their hearts first; they normally burst forth in their own arguments with raw emotion. But they perceive adults as more measured and thoughtful in voicing their opinions.

That has not been the case lately. People have not been listening to one another; instead, they have dismissed those who disagreed with them as illogical, crazy, or worse. My concern about the effects of all this rancor on young minds is that somehow it becomes normalized, that our civility – which I feel had been trending downward even before the primaries and election – has bottomed out.

True discourse begins with respectful listening

What can we do? Classroom teachers have an opportunity to reinforce the premise that only in an environment of respectful listening and acceptance can true discourse take place. While effective teachers create a culture in which put-downs, closed mindedness and lack of empathy are not acceptable, we all know that middle school students tend to test the waters.

The greatest lesson we can teach our students is that we have to meet people “where they are.” Every individual has his or her own belief system, values by which they order their daily lives, and no amount of force feeding our own ideas and opinions on them will change things. But adolescents often feel that if they just keep hammering away (as many adults did during the election) their voices will be heard.

A multi-dimensional lesson activity

The following exercise can be used for a variety of purposes across all content areas. On the face of it, it seems simplistic; however, it addresses so many layers built into the art of civil discourse.

I discovered it in a skill-building reading text (the title of which eludes me after all these years), and I found the exercise resonated with my eighth grade classes year after year.

It started out as a means to have individuals examine their own values and write about them. But later on it became a multi-dimensional lesson on focused listening, embracing others’ values, and consensus building. In addition, I had students examine their own learning and report out about their deliberation process, findings, and conclusions.

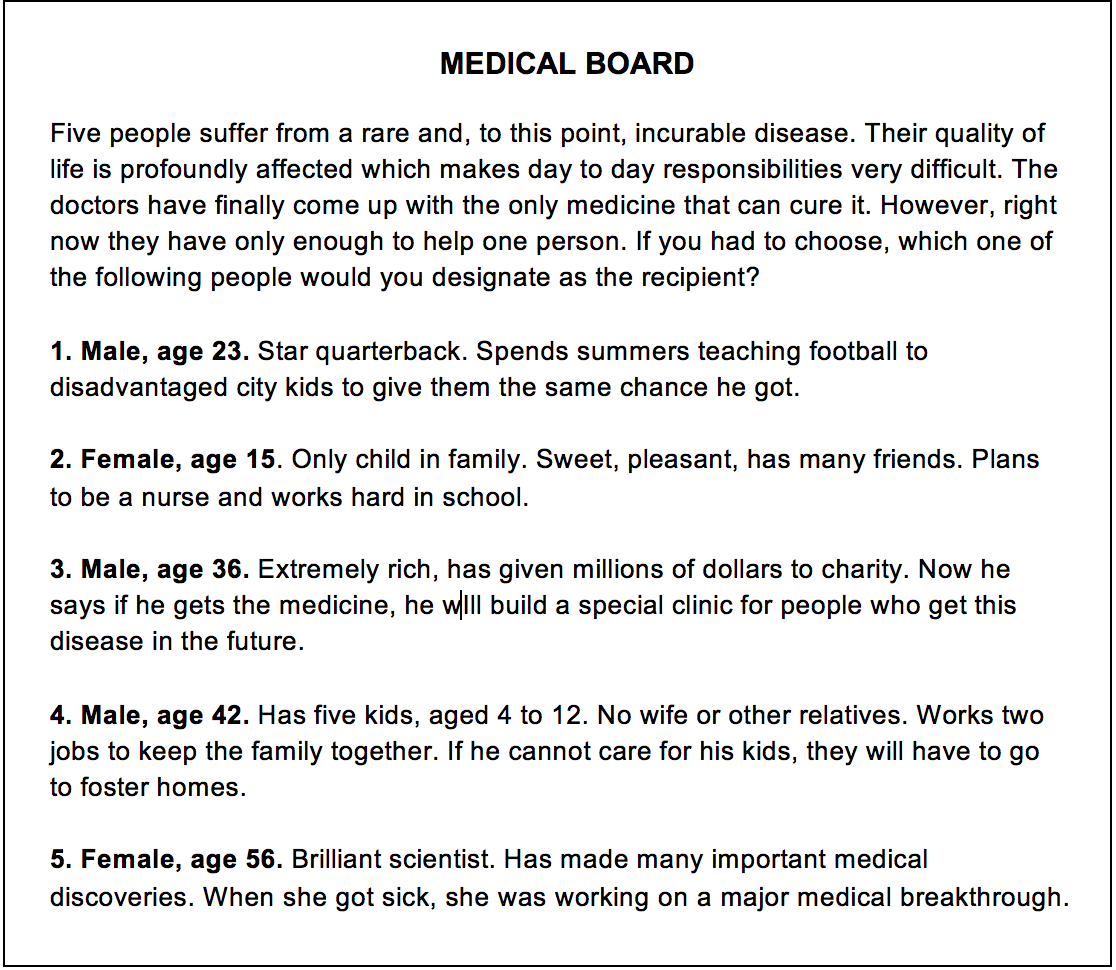

Facilitating the Medical Board activity

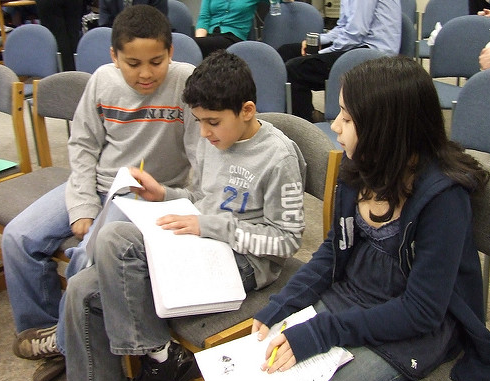

I divided the class into groups of four to five students. I told them that they were on a Medical Board that would have to make a very difficult decision. They would have to come to common consensus – there was no opting out, as one person was depending on them.

I handed them a printout of this scenario with the caveat that there would be no splitting of the dose and these were the only facts they would have to make their decision.

Besides recording their group decision, each group of students would create a narrative that summarized the discussion and interactions that brought them to the final decision.

In this summary, students would share the essence of any disagreements, describe what they discovered about the values and beliefs of the others as well as themselves, and offer their own reflections on what they had learned. Each group would present their findings to the class.

I promised that I would share my own choice at the end of the activity, but I did not want to cloud their thinking in any way beforehand.

The activity was always successful

My students always rose to the occasion! They were thoughtful and profound in their insights, honest about what had transpired in the groups, and so energized by the activity that they were running the scenario by others at lunch or sharing it at home.

Themes like “the greater good” competed with “parentless children.” Cynicism about millionaires honoring promises or a teenager turned adult following through with career goals set at age 15 came into play. They also realized that deep emotions surfaced immediately no matter how cerebral or objective they wanted to be.

Many of my students empathized with the prospect of being without parents and made their choice based on that. Just as many had dealt with the serious medical issues of family and friends, and many were willing to save the scientist on the off chance that she might succeed with her discovery. And they truly learned something about the pain of compromise and concession in coming to consensus.

Through this activity, my students experienced, first hand, the dynamic involved when people with different thoughts and feelings come together in a group; they also learned how values and beliefs inform how every person arrives at an opinion and shapes a perspective.

I praised them for their collaborative skills and their show of empathy and acceptance of other viewpoints. Most of all, I urged them to remember the process of our little scenario in the future. I wanted them to internalize the process, telling them that there would be countless opportunities in school years to come and in their long adulthood where they would be tested just as they had been in our classroom exercise.

I promised them that whenever I might need to press the reset button on civility in the classroom or guide them in debate or spirited discussion, I would remind them of that one person out of five whose life was deeply affected by their careful deliberation.

Extensions and reflections

The activity usually took two class periods, but sometimes I extended the learning by providing another moral or ethical dilemma (the Internet is an excellent source). If I wanted to broaden their critical thinking skills even further, I had groups create their own “dilemmas” or scenarios and put the class to the test. (Another viable scenario might involve a jury making a decision in a life-altering case.)

No matter what you choose to do with this activity – in your classroom or as the basis of a grade level team building exercise – you will be the facilitator and guide, but your students will teach you volumes. And won’t that be heartening after this fractious, demoralizing election.

A little sensitivity training is much needed right now: perhaps, by participating in a refresher course in the middle school classroom, adolescents can take the message about the value of civil discourse to some of the angry, conflicted adults in their midst.

Would this activity work with your students? Would you change it in any way? What might be the appropriate grade or age level? Have you tried something similar in your class? Please share your thoughts in the comments area below.

Images: Kevin Jarrett, Flickr (CC by 2.0)

________________

Wonderful idea. Thank you for reaching these important skills.

Top notch activity, Elyse! That activity can be adapted for different subjects, and could be used to reinforce decision-making and ethics. Thanks for that great idea!

Very nice article Elyse

Super lesson (not just an “activity”). In my class, we have lots of discussions about historical and current events. Respecting differing points of view requires never-ending reminders. A couple of students will simply say, “civility” when they all start talking at once or become overly emotional.

The only thing I’d change is about the single father. I teach in an area with a state children’s home. Foster homes are a reality for some of my students, so I’d tweak that a little.

Thank you for sharing!

I think this type of activity would work very well because when we were doing the activity ¨should childhood posts be deleted¨, when we grouped up with partners, we were able to come to a decision if the old posts should be deleted, and no one argued. In 7th grade, we did an activity like this, we were given topics to argue about, and the teacher would tell us if we had to argue against or for the topic, and usually, the arguments were civil. Sometimes we would even argue about serious topics in 7th grade, where we would all get into a big circle and any can join in, voicing their opinions with evidence.