Teaching How Historians Work

A MiddleWeb Blog

By Jody Passanisi & Shara Peters

By Jody Passanisi & Shara Peters

Young people today need to think like historians and not just history students. With the rapid expansion of technology and the Internet, historical information is abundant and readily accessible. Students (as we’ve discussed in earlier posts) need to think critically about what history “is,” make connections between historical themes and events, and understand perspective.

To this end, we need to start the year of study by setting the stage for the kind of meta work it takes to look at history critically. We do a mini-unit (which we co-planned with fellow MiddleWeb blogger Aaron Brock) that helps students establish a basic understanding of historiography. The unit helps our students think about what historians do, what history is, and how they themselves can be a part of the study of history.

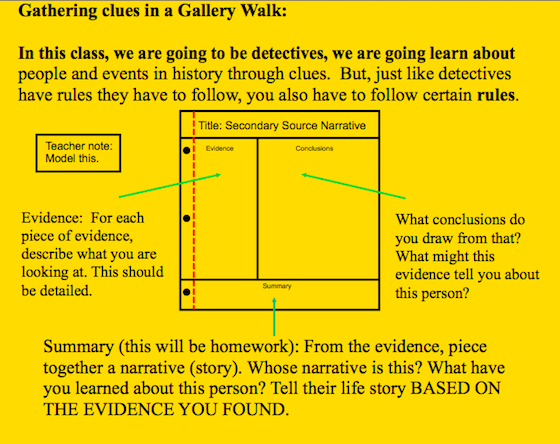

During the first week of 8th grade, our students and Aaron’s students compose their own secondary source narratives based on a collection of primary sources and artifacts that we bring them. We collect various pieces of evidence that we believe help tell the life story of a person: photographs, copies of court documents, letters, souvenir travel patches, diplomas, books, and various pieces of miscellany. We present the artifacts and source material in Gallery Walk fashion.

The students examine each artifact and pull as much data from each piece of evidence as possible–and then write the life story of this person based on the evidence they found. The subject whose life is being examined happens to be each of us–their own teacher. (We don’t tell them this in advance but they soon figure it out!)

This activity, while leading to some serious places of higher-level critical thinking and synthesis, can be adapted for younger students and is also a really good way to develop beginning of the year rapport with the students.

Getting to Know Us

Vulnerability is something to take into consideration with this activity. Our students, who we do not necessarily know very well in the first week of school, are looking at our personal belongings, reading our letters, and analyzing our pictures. They make comments about what they see, and sometimes those comments are uncomfortable to hear.

But in the three years we’ve used this project to launch our history studies, we’ve found that many students feel more comfortable with us because we have shared so much of ourselves early in the year.

Based on the “secondary sources” we’ve shared, they know things about difficult middle school experiences, awkward high school plays, the relationships we had/still have, the places we’ve been, and the things that are important to us. (They also tend to get a kick out of knowing our middle names.) Though it does put us in a place of vulnerability, this assignment has set a wonderful tone for our relationship-building with our students.

The Discipline of History

Unlike historians who write about things that happened long ago, after our students write their narratives, they have the opportunity to talk to the subject of their studies and find out if their interpretations were accurate.

They discover that the twin brother they were sure one of us had was actually Shara’s cousin who is one month younger than she. They learn that the Starbucks apron was not a Halloween costume, but that her coffee shop job helped put Shara through college. They see that Jody’s middle school boyfriend did eventually turn out to be her husband.

At the end of the activity, each student is asked to answer the following question: What did this activity teach you about history? Most of them answer, in language of their own, something like this: History is a series of narratives based on evidence and the perspective of the people writing it. This sets the tone for the rest of the school year, where we analyze bias and perspective in historical writing.

What we like best about this activity is that it helps students to experience the historian’s work for themselves. They tend to be much more sympathetic and understanding toward historical authors and their writing process as they begin to analyze bias. We could simply start the year by reading them a definition of history, and tell them that the analysis of evidence is hard to do, but that would not be nearly as meaningful.

Getting to Know the Students

Students can then apply this secondary source narrative to themselves, bringing in some artifacts and primary source documents that convey a sense of their lives. This information is of course, not only helpful to further concretize the understanding of historiography, but is a also a great way for the teacher to see what is important to the students, and find out information about them through an activity that can be tied to the curriculum.

Students still refer to the secondary source narrative document throughout the year–Just a few days before graduation a student was talking about the difference between primary and secondary sources by using the example of a teacher’s birth certificate: “The birth certificate is the primary source, remember, and the secondary source was the narrative, see?”

How do you convey the meta concept of historiography to your students?

Great activity. I would love to try it with my 8th graders next year. Only thing is I loop with my students. I have them as seventh graders and they know me pretty well by 8th grade.