Learning Through Play: Perfect for Middle School

By Chris and Katie Egan Cunningham

One of the truisms that we’ve learned in our time leading and working with middle school students is that, while they can seem – and crave to be seen – as older and more mature than elementary students, they are still very much children. And one of the most important needs that remains true for them is that they crave the opportunity to play.

Of course, for their sakes, and perhaps for our own as middle school teachers, we shy away from the very notion of play. We buy into the false dichotomy that learning is work and therefore cannot take place during play.

If students are enjoying themselves then they must not be learning very much. We use the word “engagement” instead as it seems more appropriate for their developmental stage and doesn’t cause us feelings of guilt and wasted time.

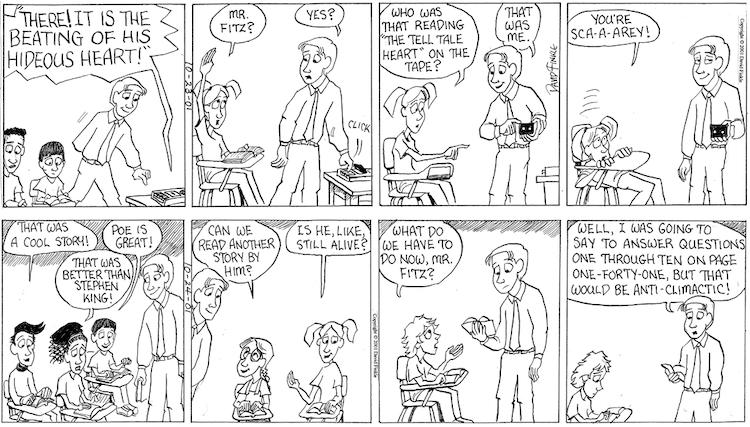

But is there truly a difference between genuine engagement and play in the middle school classroom? The hallmarks of play, as outlined by Stuart Brown (2010) in his seminal work Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul, include an inherent attraction, a diminished consciousness of self, improvisational potential, and a desire to keep the play from ending.

As any middle school teacher who has run a truly engaging class debate, historical simulation, or lighthearted activity knows, these aspects of play, infused as a key part of learning, are often at the heart of good middle school teaching. When learning feels playful, we don’t want it to end.

We know the power of learning through play

It feels strange to be arguing in favor of play—we know, deep down, that it’s important, and nearly 20 years of educational and psychological research supports this. We know now, thanks to brain imaging, that play and rest are the physical states when learning actually occurs in the brain, when neural pathways are strengthened. It’s not for nothing that some of our best ideas as adults come in the shower when the routine is automatic and we’re primed to think freely.

Play is also at the heart of creativity, intellectual curiosity, and strong relationships – all essential to joyful middle school experiences. Yet, the stark increases in anxiety, depression, and stress among our youth is a lagging indicator that we’re likely not attending to our adolescent students’ basic need to play.

Play shifts as it enters the middle school classroom and takes on new forms, but at heart, the best lessons that we’ve ever taught have been when we’ve given ourselves permission to play – to play with words, to play with perspectives, and to play with ideas.

While there are endless variations on these three themes, we believe that teachers can and should look for opportunities to better engage their students by tapping into their innate desire to play.

Verbal Play

While middle school students can often shy away from physical play out of a sense of adolescent self-consciousness, one of the easiest ways to play in the middle school classroom is to play with words.

Vocabulary lessons and grammar lessons with a sentence composing approach are ideal for this type of verbal play. We like the process of using shared digital discussion threads to facilitate this type of play as it provides students with the audience of peers that they desire and the immediate access to participate in a game.

A teacher might challenge each student to use a vocabulary word in a sentence and complicate the task by asking them to include a particular grammatical construction – a phrase, clause, or piece of punctuation – in their sentence as well. The sentence is written and shared with the class via a digital discussion thread that is projected for all of the students to see.

The teacher can work as editor in real time, deleting sentences that don’t demonstrate an understanding of the vocabulary word or the appropriate use of the grammatical construction, and asking students to repost the sentence after correcting the error.

An audience of peers is often a critical component of this manner of verbal play, for what adolescent student doesn’t want to crack a joke that makes her classmates laugh? If the teacher makes sure to maintain a lighthearted manner, students will work to make one another and the teacher laugh – all while building their vocabulary and understanding of more complex sentences.

Caption contests are similarly fantastic vehicles for verbal play in the classroom: The cartoon archive of The New Yorker can provide teachers with a nearly endless supply of terrific images that students will work hard to provide witty, thoughtful, and hilarious captions to – all while building their understanding of puns, tropes, allusions, and idioms.

Finally, we bring verbal play into the classroom every time we tell a knock-knock joke to lighten the atmosphere at the start of class. “Knock, Knock. Who’s there?” gets students’ attention every time. Knock, knock. Who’s there? Broccoli? Broccoli who? Broccoli doesn’t have a last name, silly.

Imaginative Play

While imaginative play is mostly considered the domain of early childhood, middle school students can still exercise their capacity for imaginative play in a variety of ways. What is independent reading, after all, but imaginative play?

It might take a more nuanced approach than, say, the preschoolers you might see on the playground at school, but at heart, is there really a difference between pretending to be a dinosaur and imagining Clarissa Dalloway setting off in the middle of June of 1923 to buy the flowers herself?

One of the key components of play is that it’s an activity conducted primarily for its own sake and on its own terms. Psychologist Peter Gray (2008) captures it perfectly when he explains, “Play is, first and foremost, an expression of freedom. It is what one wants to do as opposed to what one is obliged to do. The joy of play is the ecstatic feeling of liberty.” Giving students good books and the time and space to read them is one of the most playful acts imaginable.

Beyond independent reading, however, there is also a huge capacity for imaginative play when teachers introduce challenging texts such as Shakespearean plays to their middle school classes and invite students to act out the roles in front of the class. The comedies, in particular, ask students to inhabit the roles of characters, to take on new perspectives and grapple with tone, complex language and imagery, and difficult situations.

A modernized middle school version of Midsummer Night’s Dream. (Source)

The comedy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for example, is an ideal drama for adolescent students: They are given permission to play with the concept of romantic love – something they are deeply curious about – through the vehicle of the love potion and are literally encouraged to use the word “ass” in the middle of English class.

Such roleplay and perspective taking can equally apply to history classes through the use of historical simulations and debates. While sensitivity needs to be taken on the part of the teacher to avoid making light or marginalizing the role of historically disenfranchised groups of people, history is rife with complex characters and situations.

Adolescent students want to be heard and to be taken seriously – to that end, by allowing them to assume the role of historical figures and approach complex issues in history through the lenses of a simulation or historical game, students are given the chance to play with the roles of others and develop empathy towards hard historical decisions.

There are any number of digital and print resources for teachers online to harness the power of historical simulations. One collection of simulation links to consider can be found at the National History Education Clearinghouse.

Conceptual Play

While historical simulations and dramatic works ask students to play with roles and varying perspectives, there are also forms of play that ask students to play with concepts and ideas in the service of broadening their thinking and developing their opinions. Lessons and debates around civil liberties and Supreme Court cases are one way to ask students to push their thinking as they grapple with difficult questions without straightforward answers.

By asking students to argue for perspectives and points of view that they might not otherwise agree with, we can increase a student’s cognitive flexibility and help them develop a greater understanding of the perspective of others, particularly those whose ideas they might disagree with.

Again, care needs to be taken on the part of the teacher to ensure that students do not feel uncomfortable in what they are being asked to argue, particularly in cases that involve faith-based issues. Still, the opportunity to play the role of judges and lawyers in arguing for or against existing case law can be a liberating experience for students and an opportunity to play with ideas in service of trying to determine what they believe and why they believe it.

In a similar vein, middle school is the perfect age to introduce the role of debate in the classroom as it provides students with the opportunity to form and argue for their own opinions in a structured way that allows for students to play with ideas.

Asking students to debate whether or not teachers should assign homework, for example, will always produce lively results – particularly for the students who are assigned to argue in favor of homework. Giving them the opportunity to play with different ideas will provide more perspective and cultivate greater empathy than virtually any other assignment. See the New York Times Learning Network and ThoughtCo. for a variety of prompts that might prove appropriate for your middle school students.

Play is Like Oxygen – Our Students Crave It

There are plenty of reasons why teachers in middle school might shy away from play as a means of engaging students – it often seems as though there is far too much to teach and far too little time to teach it all. Still, our students crave learning to be captivating and engaging, and we know of no better way to capture their imaginations and passions than inviting them to play with us in the classroom.

More than simply fun, intentionally designing teaching and learning with play as the instructional core helps students engage in the intellectual challenges that middle school learning often requires. We know that learning anything can be frustrating. Yet, when learning is play-oriented, students are more likely to engage in the practice necessary to get stronger in any discipline.

When students engage in repeated practice, they grow in their mastery of content and skills. When students reach a level of mastery, they gain sought-after recognition of peers and their teachers. This play-practice-mastery-recognition cycle supports students to learn by starting with what is most joyful.

In our forty years combined in this field, we have found that play is the antidote to boredom, confusion, and, in many ways, the loneliness that defines this particular moment of human history. As Stuart Brown explains, play is like oxygen, “It’s all around us, yet goes mostly unnoticed or unappreciated until it is missing.”

When we use verbal, imaginative, and conceptual play as touchstones for our planning and teaching in middle school, we help students look forward to learning and school itself.